the autobiography of ‘the Queen of Bohemia’

Nina Hamnett memoirs is the record of a an artist, a Bohemian, a fringe member of the Bloomsbury Group, and towards the end of her life a woman who was more-or-less professional alcoholic. This is her interim life story, written around two thirds the way through her career when she was forty-two. Don’t expect chronological coherence or a disciplined narrative. She adopts a scatter gun approach, with famous names coming off the page in rapid succession. And she seems to have known (or met) just about everyone who was anyone in the birth of modernist art 1910-1930.

She was born in Wales in 1890 into an upper middle-class army family, and was educated at public – that is, private schools. She seems from the outset to have rebelled against the strictures of convention, and her account of her largely unhappy childhood emphasises the tomboy nature of her early years – in a way that reads like a girl’s version of Just William crossed with Adrian Mole. She only encountered the world of art when her father (who she disliked) was posted to Dublin. In her teens she attended a variety of art schools, and very rapidly began to establish contact with the people who were to form an entrée into the world of Bohemia where she felt free to breathe. Arthur Ransome, Hugh Walpole, and Aleister Crowley were early (and slightly dubious) influences.

She was born in Wales in 1890 into an upper middle-class army family, and was educated at public – that is, private schools. She seems from the outset to have rebelled against the strictures of convention, and her account of her largely unhappy childhood emphasises the tomboy nature of her early years – in a way that reads like a girl’s version of Just William crossed with Adrian Mole. She only encountered the world of art when her father (who she disliked) was posted to Dublin. In her teens she attended a variety of art schools, and very rapidly began to establish contact with the people who were to form an entrée into the world of Bohemia where she felt free to breathe. Arthur Ransome, Hugh Walpole, and Aleister Crowley were early (and slightly dubious) influences.

After inheriting fifty pounds she set herself up in Fitzrovia, and from that point onwards her connections with the artistic world developed at an astonishing pace. Mark Gertler, Dora Carrington, Wyndham Lewis, Jacob Epstein, and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska were all friends by the time she was in her early twenties. They bought each other’s paintings, often shared food, clothing, and shelter – and certainly didn’t stint themselves on whatever drinks were available.

She made a conscious effort to lose her virginity, and ended up doing so in the same rooms in Bloomsbury where Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud had lived in the 1870s. Her life at this stage appears to have been permanently blessed with good fortune. A friend gave her thirty pounds, which paid for a trip to Paris, where she met Modigliani on the first night out. There followed fancy dress parties, all night drinking, and naked dancing. Zadkine, Archipenko, and Kisling flit through the pages, and she eked out her savings by working as an artist’s model – which seems to be almost an excuse for taking her clothes off, which she was given to doing at the end of a night’s drinking.

Suddenly the indulgence of la vie boheme was shattered by the outbreak of war. She limped back home with just twopence to spare for the final tube fair. Yet after what seems like a miraculous escape from danger, she rather perversely returned to Paris to be with the man she loved – who she calls Edgar but whose real name was Roald Kristian. They returned to England, got married, and joined Roger Fry in his Omega Workshops. The subsequent war period is an odd mixture of the first bombing raids on London, Zeppelins bursting into flames, and scrounging drinks in the Cafe Royal. Her husband was arrested as an unregistered alien, spent time in jail, and was then deported to France, from which he never returned.

She moved into Fitzroy Square and befriended Walter Sickert. At this point her class of patrons and admirers seems to go up a notch: she met and painted portraits of the Sitwells, and yet all the time she was tempted to return to Paris, which she felt to be her spiritual home. For a time she took over Sickert’s old position of teaching at Westminster Technical Institute, but as soon as she had been paid at the end of the term and had enough for the fare, she returned to Paris.

There she rejoined her old friend Marie Wassilieff, who had become Leon Trotsky’s mistress during the war. She dined with Brancusi (a good chef) and fell for a romantic Pole who absconded with all her money and her best friend (who was better-looking). Then it was off to the south of France, staying with another Pole and visiting Tsuguharu Foujita, the Japanese artist. There were trips to Collioure, Cerbère, and Port Vendres, an illegal excursion to Port Bou in Spain, picnics, a little painting, and a lot more wine. But strangely enough she felt that the work she produced there was amongst her weakest and she concluded that she and the south of France were not truly compatible.

It’s difficult to tell the exact year or even the rough period in which many of these events take place – but the drinks are recorded with never-ending enthusiasm – including cider laced with Calvados, stout with champagne (at that time known as ‘Turk’s Blood’) and a mixture of absinthe, gentian, and brandy which sent one of her friends into a catatonic spasm and even she admits she could not choke down. Despite the all night parties and the rivers of champagne, the element of bohemianism continues with living in unheated flats where the water freezes in the sink at night.

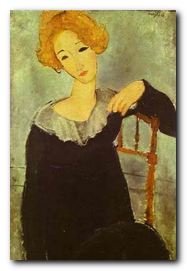

Dolores Courtney by Nina Hamnett

At one point Aleister Crowley introduced a new cocktail containing laudanum, and Hamnett fills in his background, including the practice of Black Magic on a Greek island. For this accusation he sued her in court when the memoirs were published – and lost his case. The resulting scandal sent sales of the book soaring. She met Ford Maddox Ford and Gertrude Stein, then smoked hashish with Cocteau and Raymond Radriguet who opened a new restaurant called Le Boeuf sur le Toit (immortalised by the Darius Milhaud composition).

Parties start off late in the evening, go on from one night club to another, and end up in Les Halles around 8.00 am with breakfast and more drinks. There was another more successful visit to the south of France – St Juan les Pins and Nice which was then becoming fashionable where she sang with Rudolph Valentino (full name Rodolfo Alfonso Raffaello Pierre Filibert Guglielmi di Valentina d’Antonguolla) who she later introduced to James Joyce. As the memoirs go on, the characters become more and more eccentric – including a lady acrobatic dancer who travelled with two pet monkeys and a snake. Feeling an exhibition coming on, Hamnett returned to London, where her travelling companion managed to set fire to a friend’s flat. The exhibition was a disaster, but she returned to Paris and ended up singing to an audience of Stravinsky and Diaghilev.

The memoir ends with a quite moving account of the funeral of Raymond Radriguet (Cocteau’s lover) who died at only twenty years old, and an idyllic further stay in Grasse in the south of France where she sang songs for fellow guest Francis Poulenc. The account stops abruptly some time around 1926, when she returned from France to take up residence permanently in Fitzrovia, where she became known as the ‘Queen of Bohemia’. There is actually a follow-up volume to these memoirs entitled Is She a Lady? published in 1955, a year before she threw herself out of the window of her flat and was impaled on the area railings below. She lingered painfully in hospital for three days, where her last words were “Why don’t they let me die?”

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2014

Nina Hamnett, Laughing Torso, London: Virago Press, 1984, ISBN: 860686507

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on literary studies

More on the arts