tutorial, critical commentary, plot and study resources

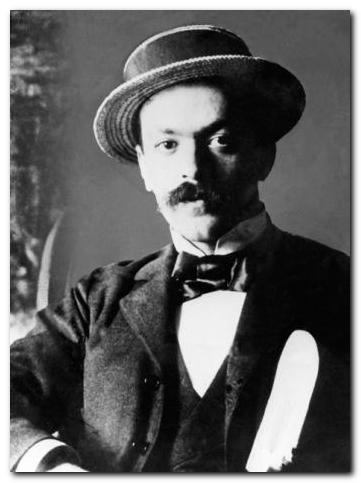

As A Man Grows Older (Senilità) was first published in 1898, and like all of Italo Svevo’s other books, it was published at his own expense. His first novel A Life (Una Vita) had appeared five years earlier and had been completely ignored. The same fate befell Senelità and Svevo was so discouraged by this lack of success that he virtually gave up writing for the next twenty-five years. But in 19o7 he was being tutored at the Berlitz School of languages in Trieste by a young James Joyce who had gone to live in exile there. Svevo showed the novel to Joyce, who encouraged and championed his work. It was Joyce who suggested the English title for the novel, and it was eventually translated into English in 1932.

As A Man Grows Older – commentary

Modernism

At a surface reading, As A Man Grows Older appears to be a rather traditional, low-key novel whose subject is not much more than an unsuccessful love affair. But it has many of the elements of modernism that were to be developed in the three decades that followed its publication.

The novel has a noticeable lack of dramatic tension, and attention is focussed instead on psychological analysis and presentation. The protagonist is an anti-hero who fails in almost everything he attempts. There are also modernist elements of unreliable witness, since the majority of events are seen from Emilio’s point of view, and he repeatedly misjudges people and attributes motives to other characters for which he has no evidence, and these attributions often turn out to be wrong.

There is a great deal of emphasis on the modern city as the theatre of events. All the drama in Emilio’s life takes place between the claustrophobic apartment he shares with his sister, and the public spaces which are the backdrop to his courtship of Angiolina

Characters

Emilio is both the protagonist of the novel, and the point of view through which almost all events are seen. He wishes to present himself in a positive light – but he is inept, he deceives himself, misreads others, and is a self-deceiving character, full of comic contradictions. There is a persistent disjuncture between his intentions and his actions. He is irresolute, he changes his mind, is indiscreet, and is trapped in what is often seen as a satirical or ironic attitude to life.

Stefano is something of an alter-ego figure to Emilio. He is muscular, handsome, and energetic – everything that Emilio is not. He is a rich and successful artist (though very little convincing evidence is provided for this) and most importantly he is successful with women. Emilio looks to him for advice regarding his love life and even his dying sister.

Angiolina is presented largely from Emilio’s point of view as an attractive woman, but it becomes rapidly obvious to the reader that she is first a flirt, then a schemer, and finally (even to Emilio) a whore. She is certainly a convincingly erotic figure, but from the start we know she has a record of former affairs (with Merighi for instance). For a poor girl, she is also suspiciously well dressed and has a luxuriously furnished room in the family apartment.

Her scheming nature is revealed when she devises the strategy of establishing a ‘decoy’ relationship as a safety net before she gives herself to Emilio. She becomes engaged to the ugly tailor Volpini as a social fall-back. But all this time she is accepting money from Emilio, and eventually her stories of visiting the Deluigi family are exposed as lies. At the end of the novel she has run off to Vienna with a man who has robbed a bank.

The modern city

It is interesting to note that As A Man Grows Older was written in a period at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century which saw the production of a number of novels that featured the city as the symbol of modern industrial and commercial life (though Charles Dickens had done the same in the middle of the nineteenth century for the establishment of the Industrial Revolution).

Andrei Biely’s Petersburg appeared in 1916, set in what was then the capital of pre-revolutionary Russia. In 1922 James Joyce’s Ulysses featured the Irish capital Dublin as it was in 1904. Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, published in 1925 is set exclusively in London, and Alfred Doblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929) is a portrait of the capital of the Weimar republic of the 1920s. Similarly, a huge amount of Kafka’s work is set in Prague, although he rarely names the streets and buildings, and Manhattan Transfer (1925) by John Dos Passos is almost a prose poem to New York City.

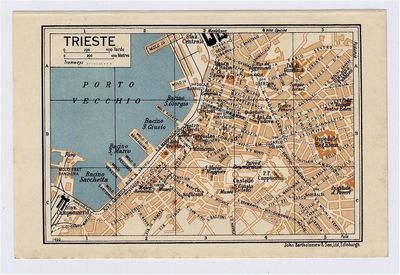

What all these novels did was to position the modern city as the location of modern sensibility. All the events of As A Man Grows Older take place in Trieste – which at that period was the fourth largest city of the Hapsburg Empire, its most important port, and a centre for literature and music. It is entirely in keeping with this culture that Emilio has published a novel, and at one point attends a concert of Die Walküre.

To many readers (particularly English-speaking) Trieste probably seemed like ‘a faraway place’ of no consequence that they had never heard of – but in fact it was a crucial centre of commercial and military power in an Empire which just happened to be on the verge of collapse. Svevo was an appropriate chronicler of its fortunes in the character of Emilio Brentani who symbolises lethargy, failure, despondency, and self-regard.

The complex relationships between Svevo’s work and language with these political ambiguities are addressed by Eduardo Roditti in his introduction to Confessions of Zeno:

Svevo’s works are indeed difficult to place properly in the complex and conflicting traditions of the Italian novel. The society that he describes is not typically Italian: his characters illustrate many qualities and faults of the Austrian bourgeoisie; his language, far from being the literary Tuscan of classical idealists or a colourful dialect such as the regional realists or Veristi affected, is rather the sophisticated and nerveless jargon of the educated Triestine bourgeoisie which spoke Italian neither as a literary nor as a national language, but as a convenient and easy manifestation of local patriotism.

The Kafka connection

The Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges, discussing similarities in the work of Robert Browning and Franz Kafka, observed:

The poem ‘Fears and Scruples’ by Browning foretells Kafka’s work, but our reading of Kafka perceptibly sharpens and deflects our reading of the poem. Browning did not read it as we do now. In the critics’ vocabulary, the word ‘precursor’ is indispensable, but it should be cleansed of all connotation of polemics or rivalry. The fact is that every writer creates his own precursors. His work modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future.

There is a very good case to be made for Svevo as a precursor to Kafka. Emilio Brentani the contradictory, obsessive, and self-analysing protagonist of As A Man Grows Older could step directly out of any number of Kafka’s stories and novels – from Gregor Samsa in Metamorphosis to Joseph K in The Trial.

But there are equally good reasons of a material, geographic, and cultural origin to explain the similarity between the two writers. First, the two men were contemporaries. Although Svevo was older and started writing earlier, they died within four years of each other in the 1920s. Second, they were both born in what was then the Hapsburg Empire, the Austro-Hungarian political dynasty whose domination reached from Prague to the Mediterranean port of Trieste.

Both Svevo and Kafka had fathers who were German-Jewish businessmen, and both of them were non-practising Jews. Both writers were raised in a linguistically ambiguous environment. Svevo’s family spoke a Triestine dialect, but Svevo himself was educated in German and wrote in Italian. Kafka lived in a Czech culture, was part of a Jewish family, and was educated (and wrote) in German. This level of cultural ambiguity was a product of the imperialism of the Hapsburg Empire which had sought to impose itself on very diverse ethnic groups and nationalities. As writers, both of them worked professionally in commercial offices – Svevo in banking, Kafka in insurance – and both of them wrote in the evening, produced a lot, but published little.

There are two further similarities. Both of them chose neurotically obsessive characters as their protagonists – characters who are ill at ease in the society they inhabit. When a problem occurs, every possible explanation or solution is examined in fine detail, including the possible motives of the other people involved. This level of pathologically neurotic behaviour is a function of both social insecurity and existential anxiety – both of which became well-recognised features of the early twentieth century. It is no accident that writers such as Svevo and Kafka were interested in the writings of Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, and Freud. Indeed, Svevo went on to produce his third novel Confessions of Zeno entirely posited on the notion of a character who is undergoing Freudian analysis – with a semi-comic lack of success.

The second similarity is the spatial obverse of the capital city as a setting of events – the family apartment building as the site of claustrophobic domestic life. Both writers feature heavily the geography of the apartment with its adjoining rooms, its lack of privacy, and its inhabitants who are forced to overhear each other’s conversations and take into account sleeping arrangements and the clothes they can wear.

The apartment is technically the scene of private, domestic life as distinct from the public life of the streets. But the contiguity of the tiny rooms becomes an oppressive symbol of the intrusion of domestic responsibilities onto the dignity of the individual. At one point Emilio overhears his sister’s private thoughts because she talks in her sleep, and then is forced to hold a conversation with her conducted through the keyhole of an adjoining door, all the time dressed in his nightshirt. This is the sister who will shortly afterwards die very painfully in the very same room, dressed only in her own thin chemise.

As A Man Grows Older – study resources

![]() A Life – Secker & Warburg- Amazon UK

A Life – Secker & Warburg- Amazon UK

![]() A Life – Secker & Warburg – Amazon US

A Life – Secker & Warburg – Amazon US

![]() As A Man Grows Older – NYRB Classics – Amazon UK

As A Man Grows Older – NYRB Classics – Amazon UK

![]() As A Man Grows Older – NYRB Classics – Amazon US

As A Man Grows Older – NYRB Classics – Amazon US

![]() Confessions of Zeno – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Confessions of Zeno – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Confessions of Zeno – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Confessions of Zeno – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Italo Svevo: A Double Life – Clarendon Press – Amazon UK

Italo Svevo: A Double Life – Clarendon Press – Amazon UK

![]() Italo Svevo: A Double Life – Clarendon Press – Amazon US

Italo Svevo: A Double Life – Clarendon Press – Amazon US

![]() Svevo’s London Writings – Troubador Press – Amazon UK

Svevo’s London Writings – Troubador Press – Amazon UK

![]() Svevo’s London Writings – Troubador Press – Amazon US

Svevo’s London Writings – Troubador Press – Amazon US

As A Man Grows Older – chapter summaries

I. Emilio Brentani works in an insurance office, has published a novel, and lives a quiet humdrum existence with his younger sister, who looks after him. When he meets attractive young Angiolina he thinks he can enjoy a flirtation without any responsibilities or consequences. He learns that she has been involved in romantic intrigues in the past, but this only arouses his interest even more. He confides in his spinster sister Amalia.

II. Emilio rather gauchely questions Angiolina about her past. He has no real experience of life himself, but he conceives a plan of ‘educating’ her. He misinterprets her reactions to him and advises her to be more unscrupulous, which she finds insulting. He objects to her name, and uses French diminutives when addressing her. At home his sister reproaches him for leaving her alone, which only makes him angry.

III. Emilio calls unannounced at Angiolina’s house and is vexed to see that she has photos of men in her luxurious reception room. When she goes away to visit some friends of her family, Emilio criticises her to his friend Stefano Balli. Later, as he and Angiolina approach the point of sexually consummating their relationship, she suggests that they need a third party on whom they could blame any ‘consequences’. But when she announces that she has become engaged to Volpini, a short and ugly tailor, Emilio thinks of her as a ‘lost woman’.

IV. Emilio is disconcerted by Angiolina’s flirtatious behaviour when they are in public together. He seeks advice from his fiend Stefano, who suggests an outing a quatre with his girl friend Margherita. But when they meet, Stefano behaves boorishly and flirts with Angiolina, who responds coquettishly. Volpini the tailor postpones the marriage for a year, but insists he cannot wait that long to possess Angiolina.

V. When Stefano calls to see Emilio the next day his friend reproaches him for his bad behaviour. They argue and Emilio’s sister (who is in love with Stefano) is asked to adjudicate in the dispute. She takes Stefano’s part in the disagreement. Over dinner Stefano boastfully recounts the story of his rich patron who has left him all his money. Stefano discovers that his girlfriend Margherita has other men in her life, and he vows to get rid of her.

VI. Stefano sees Angiolina in town with an umbrella-maker. He sends for Emilio to expose her duplicity. He urges Emilio to give up Angiolina, as he will give up Margherita. Emilio rehearses how he will avenge himself on Angiolina, and walks around the town trying to find her – without success. He goes home to hear his sister talking in her sleep.

VII. Next day he goes to Angiolina’s house intending to expose her duplicity – but he fails to do so. She lies to him about the previous night. Eventually he breaks off the relationship, then walks around town looking forward to meeting her again ‘some time’. He meets Sorniani who confirms that Angiolina has had several lovers. Then he bumps into Leardi, from whom he tries to extract further information about Angiolina, but without success.

VIII. The next day Emilio confers with his friend Stefano again, and is clearly jealous of his friend’s liberty to have access to Angiolina. Overhearing his sister talking in her sleep again about Stefano, he realises that she is in love with him, and vows to ‘save’ her. After another dinner, he accuses Stefano of compromising Amalia by his regular visits. Stefano protests his innocence, and the two friends are eventually reconciled.

IX. Stefano stops visiting the house, which makes Emilio feel very sorry for his sister. He confides in her about Angiolina, who he has not seen for a week. She cries and complains that Stefano has no right to assume that he is compromised by their regular meetings. She insists that Emilio make him resume his visits to the house. But when he does visit again he behave coldly towards Amalia. Emilio takes his sister to a concert, and feels uplifted by the music of Die Walkuyrie.

X. Emilio’s anguish regarding Angiolina grows less, and he begins writing again, turning his relationship with Angiolina into a novel. But he is not satisfied with the results. He wants to see Angiolina again, and so does Stefano, who has the pretence that he wishes to model her. When Emilio meets Angiolina in the Gardino Pubblico one night, they become reconciled. She reveals that she has given herself to Volpini, but she takes Emilio back home and goes to bed with him. She asks him to keep the fact secret, to guard her social reputation. He immediately tells Stefano about it. He hires a room in a house, but the very gestures and language Angiolina uses inflame his jealous fear that she has other lovers. He is due to be reproached by her father, but the old man turns out to be slightly crazy.

XI. Stefano makes the sculpture of Angiolina, but he respects Emilio’s jealous fears. Emilio visits the artist’s studio where Stefano is seen as a positive and creative being. Emilio is happy in his sexual relationship with Angiolina, but he becomes jealous again when he thinks it is a result of Stefano’s influence. The tailor Volpini breaks off his engagement to Angiolina because of her reputation. Emilio helps her to write a letter back to him in response.

XII. When Emilio returns home he finds Amalia in a delirious state. A helpful neighbour stays with her whilst he goes to Stefano for advice. A doctor is summoned: he suggests that Amalia has been drinking. Emilio is doubtful about both his diagnosis and his remedial prescription. Emilio feels guilty about neglecting his sister, and thinks this is a good reason for breaking off his relationship with Angiolina. When Stefano reveals that Angiolina has made advances to him, Emilio meets her and challenges her with accusations of multiple infidelities, calling her a whore. They argue, whereupon she leaves him..

XIII. Amalia’s delirium continues. She invents a rival called Vittoria, and drifts from one deluded topic to another. The neighbour Elena tells them the sad story of her ungrateful stepchildren, during which more of Angiolina’s lies are revealed. Emilio wants to see her again – just to reproach her. Meanwhile he discovers that Amalia has been taking drugs. Here delirium eventually peters out, and she dies.

XIV. Some time later Emilio hears that Angiolina has run off to Vienna with man who has robbed a bank. He visits Signora Elena and then Signora Zarrii, and ends by blending together memories of both Angiolina and Amalia to produce a comforting amalgam of the two.

As A Man Grows Older – principal characters

| Emilio Brentani | a bachelor insurance clerk (35) |

| Amalia Brentani | his younger sister, a plain spinster |

| Angiolina Zarri | a poor but very attractive young woman |

| Signora Zarri | Angiolina’s mother |

| Stefano Barri | Emilio’s best friend, a rich sculptor |

| Sarniani | a lady’s man and gossip |

| Merighi | Angiolina’s former lover, a businessman |

| Leardi | a womaniser |

| Datti | a photographer |

| Volpini | a small ugly tailor, Angiolina’s fianceé |

| Margherita | Stefano’s tall girlfriend |

| Signora Paracci | landlady of a rooming house |

| Signora Elena Chierici | Emilio’s helpful neighbour |

© Roy Johnson 2016

More on Italo Svevo

Twentieth century literature