sample from HTML program and PDF book

1. Capital letters in essays are always placed at the beginning of a sentence, and they are used for all proper nouns:

He slowly entered the room, accompanied by his friend James Bowman.

2. They are used when a particular thing is being named. For instance

| days | Wednesday, Friday |

| places | East Anglia |

| rivers | the river Mersey |

| buildings | the Tate Gallery |

| institutions | the Catholic Church |

| firms | British Aerospace |

| organisations | the National Trust |

| months | April, September |

3. However, when such terms are used as adjectives or in a general sense, no capital is required:

the King James Bible BUT a biblical reference

Manchester University BUT a university education

4. Capitals are used when describing intellectual movements or periods of history:

Freudian Platonism Cartesian

The Middle Ages the Reformation

5. They are also used in the titles of books, plays, films, newspapers, magazines, songs, and works of art in general. The normal convention is to capitalise the first word and any nouns or important terms. Smaller words such as and, of, and the are left uncapitalised:

A View from the Bridge

The Mayor of Casterbridge

North by Northwest

The Marriage of Figaro

6. The convention for presenting titles in French is to capitalise only the first or the first main word of a title:

A la recherche du temps perdu

La Force des choses

7. However, there are many exceptions to this convention:

Le Rouge et le Noir

Entre la Vie et la Mort

8. In German, all nouns are given capitals:

Reallexikon zur deutschen Kunstgeschichte

9. Works written in English which have foreign titles are normally

capitalised according to the English convention:

Fors Clavigera Religio Medici

10. Interesting exception! Capitals are not used for the seasons of the year:

autumn winter spring summer

© Roy Johnson 2003

Buy Writing Essays — eBook in PDF format

Buy Writing Essays 3.0 — eBook in HTML format

More on writing essays

More on How-To

More on writing skills

This tutorial looks at the famous opening passage of Bleak House and examines Dickens’s use of language, simile, and metaphor. It argues that whilst Dickens is often celebrated for the vividness of his descriptions, the true genius of his literary power is in imaginative invention.

This tutorial looks at the famous opening passage of Bleak House and examines Dickens’s use of language, simile, and metaphor. It argues that whilst Dickens is often celebrated for the vividness of his descriptions, the true genius of his literary power is in imaginative invention. This is the first of two close reading tutorials on Conrad’s early tale An Outpost of Progress. This one looks at the opening of the story and examines the semantic values transmitted in Conrad’s presentation of the narrative. That is, how the meaning(s) of the story are embedded in even the smallest details of of the prose.

This is the first of two close reading tutorials on Conrad’s early tale An Outpost of Progress. This one looks at the opening of the story and examines the semantic values transmitted in Conrad’s presentation of the narrative. That is, how the meaning(s) of the story are embedded in even the smallest details of of the prose. This tutorial looks at one of the opening paragraphs of Katherine Mansfield’s short story The Voyage. It covers the standard features of a writer’s prose style – in the use of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, tone, narrative mode, and figures of speech; but then it singles out the crucial issue of point of view for special attention. Mansfield was one of the only writers to establish a first-rate world literary reputation on the production of short stories alone.

This tutorial looks at one of the opening paragraphs of Katherine Mansfield’s short story The Voyage. It covers the standard features of a writer’s prose style – in the use of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, tone, narrative mode, and figures of speech; but then it singles out the crucial issue of point of view for special attention. Mansfield was one of the only writers to establish a first-rate world literary reputation on the production of short stories alone. Virginia Woolf used the short story as an experimental platform on which to test out her innovations in language and fictional narrative. This tutorial offers a detailed reading of the whole of the experimental story Monday or Tuesday. It shows how its mixture of lyrical images, speculative thoughts, and fragments of story-line add up to more than the sum of its parts.

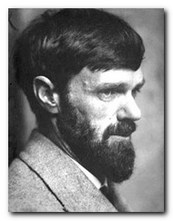

Virginia Woolf used the short story as an experimental platform on which to test out her innovations in language and fictional narrative. This tutorial offers a detailed reading of the whole of the experimental story Monday or Tuesday. It shows how its mixture of lyrical images, speculative thoughts, and fragments of story-line add up to more than the sum of its parts. D.H.Lawrence was the first world-class writer to have emerged from the working class. His work was passionate, sensual, and controversial. This tutorial looks at the opening paragraphs of his short story Fanny and Annie published in 1922. It considers in particular his use of the rhetorical devices of repetition and alliteration to impart a poetic impressionism to his writing.

D.H.Lawrence was the first world-class writer to have emerged from the working class. His work was passionate, sensual, and controversial. This tutorial looks at the opening paragraphs of his short story Fanny and Annie published in 1922. It considers in particular his use of the rhetorical devices of repetition and alliteration to impart a poetic impressionism to his writing.