an essay-review of the collected letters

Saul Bellow left behind a sizeable body of fiction , travel writing, and essays on his departure in 2005 – but he was also a prolific correspondent. This huge selection of his letters includes examples from seven decades of his adult life. He writes to friends, fellow writers, academic colleagues, lovers, wives, and even fans.

The earliest letters date from the 1930s when he was a student and a Trotskyist. They deal with political issues arising from the world economic depression, the gathering war in Europe, splits on the Left, and then problems with his first marriage.

His spiritual and intellectual home was Chicago, where he had grown up, but he migrated to New York to pursue his literary ambitions. He earned his living as a teacher and a journalist, and had the usual difficulties getting his early work accepted. There were a couple of false starts before his first novel Dangling Man was published in 1944.

His skills as a writer come into shining prominence when he writes a long and superbly entertaining letter to his literary agent Henry Volkening. It describes several weeks of his ‘exile’ in Europe on a Guggenheim fellowship. He travels between Paris, Geneva, and Marseilles, pursued by a rapacious, opium-smoking socialite vamp, gets drunk with Scott Fitzgerald, and is thrown out of hotels – all of which turns out to be pure fantasy (Fitzgerald having died ten years previously).

The letter dates from around the time that he began writing The Adventures of Augie March, a novel that was to prove his big break-through success in 1953. This free-wheeling approach to narrative invention and verbal exuberance is precisely what established his distinctive voice as a modern novelist.

However, it’s not all fun. Some of the letters make for quite uncomfortable reading. Bellow had friendships with fellow writers which sometimes included elements of rivalry. When differences become apparent he can take a lofty, holier-than-thou tone with correspondents. His childhood friend Isaac Rosenfeld is the object of a spiteful clash over merely teaching in the same university (New York). And he was downright rude to his English publisher, John Lehmann.

If you can find nothing better to say upon reading Augie March than that you all “think very highly of me”, I don’t think I want you to publish it at all … Either you are entirely lacking in taste and judgment, or you are being terribly prudent about the advance. Well, permit me to make it clear once and for all that it doesn’t make a damned bit of difference to me whether you publish the novel or not. You have read two-thirds of it, and I refuse absolutely to send you another page. Return the manuscript to Viking if you don’t want to take the book.

On the other hand he is very loyal to many of his friends – to John Berryman, Philip Roth, Ralph Ellison, and John Cheever in particular. Even to Delmore Schwartz, his early mentor who eventually descended into paranoia and turned against him (and everyone else).

It’s amazing to note how he goes on writing, no matter what the circumstances. Whilst holed up in an isolated shack outside Reno, Nevada (waiting for his first divorce to come through) he was finishing off Seize the Day (1956) and starting work on Henderson the Rain King (1959) at the same time.

In a single year he published Henderson, underwent psycho-analysis, started a magazine (The Noble Savage), and received a huge grant ($16,000) from the Ford Foundation, which he spent on a holiday in Eastern Europe. He also started writing plays – which were not successful when staged – and his second marriage came to an end when his wife Sondra filed for divorce.

Even this cornucopia of events had its further complications. He was devastated by the split from Sondra, but she assured him that there was ‘nobody else’. The truth was that she was having an affair with his friend and co-editor, Jack Ludwig. Bellow took his own revenge for this betrayal in his next novel Herzog (1964).

This use of real lives as the material for fiction became something of a leitmotiv in his work. The letters confirm that he repeatedly used events from his own life and the experiences of others as the basis for what he wrote. It is well known that Humboldt’s Gift (1975) and Ravelstein (2000) featured characters based on his friends Delmore Schwartz and Allan Bloom. Moreover, anyone reading The Dean’s December (1982) cannot fail to conclude that the story is a fictionalised account of his own visit to Bucharest which he made with his Romanian-born third wife.

This list goes on, even into shorter works such as Him with His Foot in his Mouth (1982) which is something of an apology for an insulting remark he made to a colleague years before. Similarly, What Kind of Day Did You Have? (1984) is an account of an illicit affair between his old friend Harold Rosenberg and a woman called Joan Ullman.

Some of the people concerned who recognised the origins of these stories were outraged by Bellow’s unauthorised use of biographical details in this way. Joan Ullman didn’t take kindly to having her personal life used in this way and she published her own account of events. Bellow responded with a literary shrug of the shoulders.

Suddenly in 1966 whilst still married to Susan Glassman, he fell in love with the young and single Margaret Staatz. Not surprisingly, this episode was rapidly followed by Susan’s filing for divorce.

He was an obsessive traveller, even though he often complained of the places he visited. The letters have postmarks from Lake Como, Uganda, London, Tel Aviv, Athens, Puerto Rico, and Belgrade. He was also endlessly critical of Chicago, but regularly went back there.

It’s obvious that he found teaching a necessary evil to pay the bills, yet he continued in a variety of university lectureships even after becoming commercially successful and winning both the Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize for Literature in the same year (1976). However, his multiple marriages were an expensive form of self-indulgence. The final divorce settlement from Susan Glassman left him with a bill for $500,000, plus $200,000 legal costs. Confessing to his own extravagances he says of himself “I’ve always lived like a sort of millionaire without any money”.

There is one rather curious strand to this correspondence – his lengthy exchanges with the English academic (and solicitor) Owen Barfield on the subject of Rudolf Steiner’s ‘anthroposophy’. This was a form of quasi-mystic ‘philosophy’ dealing with the condition of the human soul – the vague and abstract ruminations on which Bellow had padded out Humboldt’s Gift.

It’s a curious part of the correspondence because it is difficult to accept that Bellow took these ideas seriously when they sit so ill-at-ease with the very practical and concrete nature of his perceptions of everyday life. In his most deeply felt writing Bellow is dealing with money and sex; politics and history; gangsters, lawyers, and real estate developers; crime, violence, and shysters of all kinds. Rudolf Steiner’s notions of ‘spiritual science’, ‘esoteric cosmology’, and ‘the second coming of Christ’ simply do not fit convincingly alongside such matters. The letters confirm Bellow’s sincere personal interest in these matters, but they are not at all persuasive when he attempts to embed them in his fiction .

In 1985 his first wife Anita and his two brothers Maurice and Sam died, then his third wife Alexandra divorced him. He faced yet more draining legal costs, but without breaking his stride and at seventy years of age, he simply married his secretary Janis Freedman, who had previously been his student. A decade and a half later at the age of eighty-four he became a father for the fourth time. His eldest son Gregory was at that time fifty-five years old.

In 1994 whilst on holiday in the Caribbean, Bellow contracted a virulent strain of food poisoning that left him unconscious in a coma and on the point of death for four weeks. Recovery was slow and left him with coronary and neurological complications. From this point onwards he felt he was living on borrowed time, and his correspondence reads like a series of medical bulletins. Nevertheless he manages to throw off some thought-provoking cultural observations:

Let me add my name to the list of Freud’s detractors. If he had been purely a scientist he wouldn’t have had nearly so many readers. It was lovers of literature (and not the best kind of those) who made his reputation. His patients were the text and his diagnoses were Lit. Crit. The gift the great nineteenth century [pests] gave us was the gift of metaphor. Marx with the metaphor of class struggle and Freud with the metaphor of the Oedipus complex. Once you had read Marx it took a private revolution to overthrow the metaphor of class warfare – for an entire decade I couldn’t see history in any other light. Freud also subjugated us with powerful metaphors and after a time we couldn’t approach relationships in anything but a Freudian light. Thank God I liberated myself before it was too late.

As the years go on his letters become lengthy apologies for not having written sooner – or not having replied at all. He turns politically towards the right, and the death of one old friend after another makes him (understandably) concerned about his own mortality. Yet he goes on being creatively productive into his eighties. Many people see his last novel Ravelstein (2000) as amongst his finest.

Of course the selection of letters tend to be chosen to show the Famous Author in the best possible light – but Benjamin Taylor’s editorship presents Bellow as cantankerous, considerate, hard-working, vain, ambitious, and engaged – so we have no grounds for complaint. We are presented with The Man in Full.

© Roy Johnson 2017

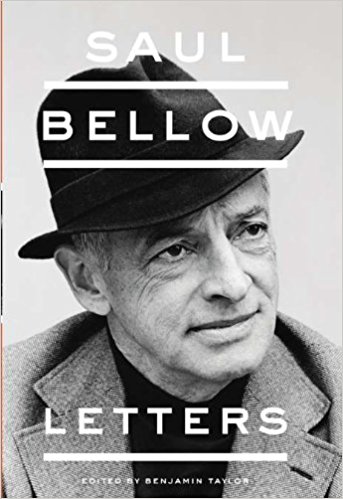

![]() Saul Bellow Letters – Viking – Amazon US

Saul Bellow Letters – Viking – Amazon US

![]() Saul Bellow Letters – Viking – Amazon US

Saul Bellow Letters – Viking – Amazon US

Benjamin Taylor (ed), Saul Bellow: Letters, New York: Viking, 2010, pp.571, ISBN: 0670022217

More on Saul Bellow

More on the novella

More on short stories

Twentieth century literature