politics, life, and literature – 1900 to 1969

Leonard Woolf was one of the longest living (1880-1976) and the most distinguished members of the Bloomsbury Group. He was a writer, a publisher, a political activist, a proto environmentalist and animal lover, a loyal friend, cantankerous employer, and a devoted husband. What’s not so well known about him is that in fact he had two ‘wives’ – the second technically married to somebody else – who happened to be his business partner. The Letters of Leonard Woolf is a definitive selection from his voluminous correspondence, which begins at Cambridge, with letters to his lifelong friend Lytton Strachey, and fellow apostles G.E.Moore and Saxon Sydney-Turner.

The manner of these early writings is surprisingly arch, full of classical references and undergraduate Weltschmerz – though no doubt this reflects the turn-of-the-century social mood amongst such a privileged elite. All of this was to change very suddenly when after doing badly in the Civil Service exams, he went to work as a colonial administrator in Sri Lanka – then called Ceylon. There he plunged into the practical affairs of running the Empire – and making a big personal success of it. It’s interesting to note that the florid rhetoric of the earlier letters is replaced by a straightforward reporting of events, and a frank expression of his feelings. His fellow Brits began to seem like something out of a bad novel:

The manner of these early writings is surprisingly arch, full of classical references and undergraduate Weltschmerz – though no doubt this reflects the turn-of-the-century social mood amongst such a privileged elite. All of this was to change very suddenly when after doing badly in the Civil Service exams, he went to work as a colonial administrator in Sri Lanka – then called Ceylon. There he plunged into the practical affairs of running the Empire – and making a big personal success of it. It’s interesting to note that the florid rhetoric of the earlier letters is replaced by a straightforward reporting of events, and a frank expression of his feelings. His fellow Brits began to seem like something out of a bad novel:

The ‘society’ of the place is absolutely inconceivable; it exists only upon the tennis-court & in the G.A.’s house; the women are all whores or hags or missionaries or all three; & the men are … sunk.The G.A.’s wife has the vulgarity of a tenth rate pantomime actress; her idea of liveliness is to kick up her legs & to scream the dullest of dull schoolboy ‘smut’ across the tennis court or the dinner table,

There are many interesting disclosures as he reveals himself to Lytton Strachey, his only confidant, who was 9,000 miles away. Woolf though that sexual desire was a ‘degradation’ – an attitude which casts light on his two later sex-free relationships. “I am really in love with someone who is in love with me. It is not however pleasant because it is pretty degrading, I suppose, to be in love with practically a schoolgirl”.

He’s also fairly unsparing in his comments on people who were later to become his famous fellow Bloomsburyites – though it has to be remembered that he had known them since they were all undergraduates together. On reading E.M.Forster’s Where Angels Fear to Tread he thinks ‘It’s …a mere formless meandering. The fact is I don’t think he knows what reality is, & as for experience the poor man does not realise that practically it does not exist’.

I detest Keynes, don’t you? Looking back on him from 4 years I can see he is fundamentally evil if ever anyone was.

When he arrived back in England on leave in 1911, is was with the vague notion of marrying Virginia Stephen, an idea that Lytton Strachey had put into his head. And marry her he did – even though Virginia refused to allow his family to the wedding and made it quite clear that she felt no physical attraction to him.

The letters are presented in separate themes which correspond to successive periods in his life – Cambridge, Ceylon, marriage to Virginia, manager of the Hogarth Press. It also has to be said that this is a rigorously scholarly production. Each section of his life has an essay-length introduction; there’s a family tree, chronological notes; biographical sketches of the principal characters, explanatory footnotes, photographs, and a huge index.

Writing as a publisher, there are some wonderfully humane letters to his actual and would-be authors, explaining the iniquities of the book trade. He was of course sealing with writers of the stature of Freud and T.S.Eliot. There’s also an extended letter to one of his best-selling authors, Vita Sackville-West (his wife’s one-time lover) which should be required reading for anyone who wants to know how the world of selling books works – even today.

He also had his finger on the pulse of the BBC and its patronising attitude to the public in a way that still rings true:

That the BBC should be so reactionary and politically and intellectually dishonest is what one would expect and forgive, knowing the kind of people who always get in control of those kind of machines, but what makes them so contemptible is that, even according to their own servants’ hall standards, they habitually choose the tenth rate in everything, from their music hall programmes and social lickspittlers and royal bumsuckers right down their scale to the singers of Schubert songs, the conductors of their classical concerts and the writers of their reviews.

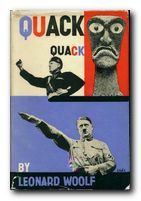

Politically, he was spot on throughout all the tensions and ambiguities of the inter-war years. Anti-Imperialist, Ant-Fascist, and supportive of the Russian revolution whilst critical of the Stalinism which caused its corruption.

One of the most interesting features of his later life is that he spent more than thirty years of it in love with another man’s wife. She lived with Leonard during the week and went back to her husband at the weekend. The husband even became Leonard’s business partner.

This is somewhat brushed under the carpet by the editor. He chooses fairly anodyne letters to Trekkie Parsons, and you would need information from other sources such as their collected correspondence (Love Letters) to realise how serious the relationship was.

It was serious enough that Leonard made Trekkie his executor and legatee in a will which was disputed by the Woolf family after his death. It was in court that the revelation (or claim) was made that they were never more than good friends.

One wonders, and boggles. But the fact is that Leonard Woolf was a great letter writer – though always seeming to be writing with the public looking over his shoulder. His correspondence should be read alongside the magnificent Autobiography, but even then you need to realise that there’s more to the story of a person’s life than the tale told by its protagonist.

© Roy Johnson 2000

Frederic Spotts (ed), The Letters of Leonard Woolf, London: Bloomsbury, Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks, 1992, pp.616, ISBN: 0747511535

More on Leonard Woolf

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

The other Press publications upon which the collection focuses are those by Virginia Woolf herself – all illustrated by her sister Vanessa Bell. There are also examples of the polemical essays published in the 1930s, which included arguments against Imperialism and in favour of feminism (of which Leonard was a champion). A short series of public letters even included ‘A Letter to Adolf Hitler’ by Louis Golding.

The other Press publications upon which the collection focuses are those by Virginia Woolf herself – all illustrated by her sister Vanessa Bell. There are also examples of the polemical essays published in the 1930s, which included arguments against Imperialism and in favour of feminism (of which Leonard was a champion). A short series of public letters even included ‘A Letter to Adolf Hitler’ by Louis Golding.