introductory guidance notes

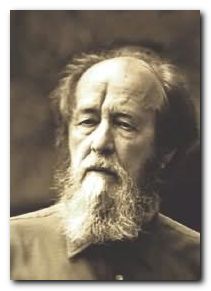

Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008 ) was both the continuation of the nineteenth century Russian realist literary tradition, and the nearest the twentieth century had to a Tolstoy figure – a great writer who became a self-appointed conscience to the Russian nation. Solzhenitsyn survived four of the most severe tests known to human beings – war, cancer, unjust imprisonment, and exile. He made all of them the materials of his fiction. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970. This did not prevent him being expelled from the Soviet Union in 1974 under Brezhnev. He then lived in the United States until he was invited back to his homeland in 1994 following the collapse of communism.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008 ) was both the continuation of the nineteenth century Russian realist literary tradition, and the nearest the twentieth century had to a Tolstoy figure – a great writer who became a self-appointed conscience to the Russian nation. Solzhenitsyn survived four of the most severe tests known to human beings – war, cancer, unjust imprisonment, and exile. He made all of them the materials of his fiction. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970. This did not prevent him being expelled from the Soviet Union in 1974 under Brezhnev. He then lived in the United States until he was invited back to his homeland in 1994 following the collapse of communism.

Most of his work is written in a simple, spare manner in which ornamentation is stripped away in favour of moral purpose. The results celebrate a stoical, almost puritan heroism in the face of all that the Russian people have had to endure – constructed poverty, war, political corruption, censorship, and totalitarian repression.

In his later years, just like Tolstoy, he abandoned literature in favour of writing moralising polemical works concerned with religious and political issues, and he is generally regarded as having drifted into something of a reactionary. However, his earlier work is well worth serious consideration.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch (1962) is a short novel that made Solzhenitsyn famous overnight. It recounts a typical day’s work, deprivation, and suffering of a prisoner in one of Stalin’s labour camps. Publication was ‘allowed’ because it suited Krushchev in his post 1956 reforms and his criticism of Stalin. The facts of prison camp life were deliberately understated to meet the censor’s requirements. It catapulted Solzhenitsyn to fame, and yet within two or three years his work was banned all over again. Beginners should start here.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch (1962) is a short novel that made Solzhenitsyn famous overnight. It recounts a typical day’s work, deprivation, and suffering of a prisoner in one of Stalin’s labour camps. Publication was ‘allowed’ because it suited Krushchev in his post 1956 reforms and his criticism of Stalin. The facts of prison camp life were deliberately understated to meet the censor’s requirements. It catapulted Solzhenitsyn to fame, and yet within two or three years his work was banned all over again. Beginners should start here.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Gulag Archipelago (1973-1978) could eventually turn out to be Solzhenitsyn’s masterpiece. It’s a three-volume encyclopedia of the forced labour camps which underpinned the communist system – from Lenin onwards. It was written in secret under incredibly difficult conditions and smuggled out to the West. It’s a history, a sociology, a complete political and social record of the labour camps. Rather unusually for Solzhenitsyn it is recounted via a series of poetic metaphors which hold together a wonderful collection of stories, statistics, and anecdotes. There are heartbreaking tales of endurance, survival, escape, and recapture. It is truly one of the great documents of historical witness. In retrospect it probably helped to bring about the collapse of the totally corrupt communist regime in the USSR. But most importantly it helps to document a tragically bleak period of quite recent European history. This is a work which could significantly affect your life.

The Gulag Archipelago (1973-1978) could eventually turn out to be Solzhenitsyn’s masterpiece. It’s a three-volume encyclopedia of the forced labour camps which underpinned the communist system – from Lenin onwards. It was written in secret under incredibly difficult conditions and smuggled out to the West. It’s a history, a sociology, a complete political and social record of the labour camps. Rather unusually for Solzhenitsyn it is recounted via a series of poetic metaphors which hold together a wonderful collection of stories, statistics, and anecdotes. There are heartbreaking tales of endurance, survival, escape, and recapture. It is truly one of the great documents of historical witness. In retrospect it probably helped to bring about the collapse of the totally corrupt communist regime in the USSR. But most importantly it helps to document a tragically bleak period of quite recent European history. This is a work which could significantly affect your life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The First Circle (1968) is set in a special research-cum-detention centre reserved for mathematicians and scientists who are nevertheless political prisoners. This is what might be called a novel of ideas, as the characters discuss the political and historical forces which have brought them to their present unjust imprisonment. Of the main characters, one is eventually released, another is sent off to a much harsher regime, and the third remains where he is. Includes a satirical portrait of Stalin.

The First Circle (1968) is set in a special research-cum-detention centre reserved for mathematicians and scientists who are nevertheless political prisoners. This is what might be called a novel of ideas, as the characters discuss the political and historical forces which have brought them to their present unjust imprisonment. Of the main characters, one is eventually released, another is sent off to a much harsher regime, and the third remains where he is. Includes a satirical portrait of Stalin.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

August 1914 (1971) is the first part of a multi-volume epic, a historical novel on a grand scale about the origins of the Soviet Union and how communism came to take root there. The cycle is called The Red Wheel, and was never finished. Solzhenitsyn sees the Battle of Tannenberg at the start of the First World War as the first major turning point in this process. Using a range of modernist and vaguely experimental techniques, he sets in motion a huge cast of characters against the backdrop of this decisive battle.

August 1914 (1971) is the first part of a multi-volume epic, a historical novel on a grand scale about the origins of the Soviet Union and how communism came to take root there. The cycle is called The Red Wheel, and was never finished. Solzhenitsyn sees the Battle of Tannenberg at the start of the First World War as the first major turning point in this process. Using a range of modernist and vaguely experimental techniques, he sets in motion a huge cast of characters against the backdrop of this decisive battle.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Lenin in Zurich (1976) is a short section from The Red Wheel which focuses largely on Lenin in exile, immediately prior to his triumphant return in a sealed train to St Petersburg’s Finland Station. It’s a very interesting study, because Solzhenitsyn is clearly critical of Lenin as one of the central architects of communism – yet he narrates the novel largely from Lenin’s point of view, blending a psychological character study and real historical detail with a witheringly ironic critique. Steeped in history, this is a major attempt at a political and psychological portrait of a historical figure.

Lenin in Zurich (1976) is a short section from The Red Wheel which focuses largely on Lenin in exile, immediately prior to his triumphant return in a sealed train to St Petersburg’s Finland Station. It’s a very interesting study, because Solzhenitsyn is clearly critical of Lenin as one of the central architects of communism – yet he narrates the novel largely from Lenin’s point of view, blending a psychological character study and real historical detail with a witheringly ironic critique. Steeped in history, this is a major attempt at a political and psychological portrait of a historical figure.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2009

The Heart of a Dog

The Heart of a Dog Black Snow: A Theatrical Novel

Black Snow: A Theatrical Novel A Country Doctor’s Notebook

A Country Doctor’s Notebook The Fatal Eggs

The Fatal Eggs The Master and Margarita

The Master and Margarita life, works, political persecution

life, works, political persecution The Heart of a Dog

The Heart of a Dog Eugene Onegin

Eugene Onegin A Hero of Our Time

A Hero of Our Time Dead Souls

Dead Souls Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground

From the House of the Dead

From the House of the Dead Crime and Punishment

Crime and Punishment The Brothers Karamazov

The Brothers Karamazov  Anna Karennina

Anna Karennina War and Peace

War and Peace Fathers and Sons

Fathers and Sons

We

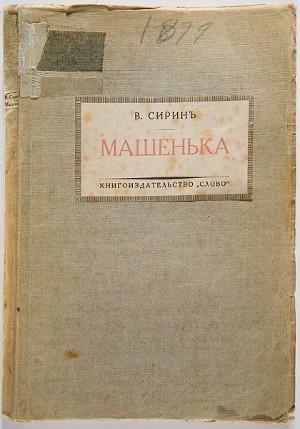

We Mary

Mary Other novels such as

Other novels such as

August 1914

August 1914 Lenin in Zurich

Lenin in Zurich