how to understand plagiarism – and avoid it

Plagiarism – definition

1. Plagiarism is defined as “Passing off someone else’s work as your own”.

2. It happens if you copy somebody else’s work instead of doing your own.

3. It also happens in those cases where people actually buy essays instead of doing the work themselves.

4. Schools, colleges, and universities regard this as a serious offence – and they often have stiff penalties for anyone found guilty.

5. Most people at school level call this ‘cheating’ or ‘copying’ – and they know it is wrong.

6. The problem is that at college or university, you are expected to use and write about other people’s work – so the issue of plagiarism becomes more complex.

7. There are also different types and different degrees of plagiarism – and it is often difficult to know whether you are breaking the rules or not.

8. Let’s start off by making it clear that all the following can be counted as plagiarism.

- Copying directly from a text, word-for-word

- Using text downloaded from the Internet

- Paraphrasing the words of a text very closely

- Borrowing statistics from another source or person

- Copying from the essays or the notes of another student

- Downloading or copying pictures, photographs, or diagrams without acknowledging your sources

- Using an attractive phrase or sentence you have found somewhere

Why is this so complex?

9. The answer is – because in your work at college or university level you are supposed to discuss other people’s ideas. These will be expressed in the articles and books they have written. But you have to follow certain conventions.

10. Plus – at the same time – you will be asked to express your own arguments and opinions. You therefore have two tasks – and it is sometimes hard to combine them in a way which does not break the rules. Many people are not sure how much of somebody else’s work they can use.

11. Sometimes plagiarism can happen by accident, because you use an extract from someone else’s work – but you forget to show that you are quoting.

12. This is the first thing you should learn about plagiarism – and how to avoid it. Always show that you are quoting somebody else’s work by enclosing the extract in [single] quotation marks.

In 1848 there was an outbreak of revolutionary risings throughout Europe, which Marx described as ‘the first stirrings of proletarian defiance‘ in a letter to his collaborator, Frederick Engels.

13. This also sometimes happens if you are stuck for ideas, and you quote a passage from a textbook. You might think the author expresses the idea so well, that you can’t improve on it.

14. This is plagiarism – unless you say and show that you are quoting someone else’s work. Here’s how to do it:

This painting is generally considered one of his finest achievements. As John Richardson suggests: ‘In Guernica, Picasso lifts the concept of art as political propaganda to its highest level in the twentieth century‘.

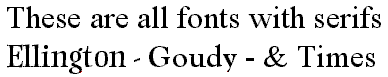

Academic conventions

15. Why do colleges and universities make such a big fuss about this issue? The answer to this is that they are trying to keep up important conventions in academic writing.

16. The conventions involve two things at the same time. They are the same as your two tasks:

- You are developing your own ideas and arguments and learning to express them.

- You are showing that you have learned about and can use other people’s work.

17. These conventions allow you to use other people’s work to illustrate and support your own arguments – but you must be honest about it. You must show which parts are your own work, and which parts belong to somebody else.

18. You also need to show where the information comes from. This is done by using a system of footnotes or endnotes where you list details of the source of your information.

19. The conventions of referencing and citation can become very complex. If you need guidance on this issue, have a look at our detailed guidance notes on the subject. What follows is the bare bones.

20. In an essay on a novel by D.H. Lawrence for example, you might argue that his work was influenced by Thomas Hardy. You could support this claim by quoting a literary critic:

Lawrence’s characters have a close relationship with their physical environment – showing possibly the influence of Hardy, who Walter Allen points out was ‘his fundamental precursor in the English tradition‘ (1)

21. Notice that you place a number in brackets immediately after the quotation. The source of this quotation is given as a footnote at the bottom of the page, or as an endnote on a separate sheet at the end of your essay.

22. The note gives full details of the source – as follows:

Notes

1. Walter Allen, The English Novel, London: Chatto and Windus, 1964, p.243

A bad case of plagiarism

This video clip features the case of Ann Coulter. She is a best-selling American writer and social critic who has extremely right-wing views.

The film raises several plagiarism issues:

- failure to acknowledge sources

- failure to quote accurately

- changing the nature of a quotation

- misleading references (citations)

- definitions of plagiarism

- plagiarism detection software

- legitimate quotation

Do’s and Don’ts

23. You should avoid composing an essay by stringing together accounts of other people’s work. This occurs when an essay is written in this form:

Critic X says that this idea is ‘ … long quotation …‘, whereas Commentator Y’s opinion is that this idea is ‘ … long quotation …‘, and Critic Z disagrees completely, saying that the idea is ‘ … long quotation …‘.

24. This is very close to plagiarism, because even though you are naming the critics and showing that you are quoting them – there is nothing of your own argument being offered here.

25. If you are stuck for ideas, don’t be tempted to copy long passages from other people’s work. The reason is – it’s really easy to spot. Your tutor will notice the difference in style straight away.

Copyright and plagiarism

26. Copyright can be quite a complex issue – but basically it means the ‘right to copy’ a piece of work. This right belongs to the author of the work – the person who writes it – or a publisher.

27. When a piece of writing is published in a book or on the Web, you can read it as much as you wish – but the right to copy it belongs to the author or the author’s publisher.

28. Nobody will worry if you quote a few words, or a few lines. This is regarded as what is called ‘fair use’. People in the world of education realise that because quotation is so much a part of academic writing, it would be ridiculous to insist that you should seek permission to quote every few words.

29. In fact there is an unwritten convention that you can quote up to 5% of a work without seeking permission. If this was from a very long work however, you would still be wise to seek permission.

30. This permission is only for your own personal study purposes – as part of your course work or an assignment. If you wished to use the materials for any other purpose, you would need to seek permission.

31. Copyright also extends beyond writing to include diagrams, maps, drawings, photographs, and other forms of graphic presentation. In some cases it can even include the layout of a document.

The Johann Hari case

A recent case which has drawn attention to subtle forms of plagiarism is that of British journalist Johann Hari. He writes articles and conducts interviews for The Independent newspaper. It was revealed that in many articles (and particularly his interviews) he had inserted quotations from the previous writings of the interviewee, or from interviews written by other journalists. In both cases the quotations were unacknowledged. .

He was criticised in particular for creating the impression that the words had been used in his own face-to-face interviews by sewing together the quotations with apparently on-the-spot dramatic context – as in “puffing nervously on a cigarette, she admitted to me that …” and that sort of thing.

When it was revealed that his prime quotations were lifted from written sources up to five years old, Hari was forced to issue an apology. He claimed that interviewees were sometimes less articulate in speech writing than in writing, and that he merely wanted to present their arguments in the best light.

This feeble ‘explanation’ ignores three of the principal issues in plagiarism. He did not produce his own paraphrases of the interviewee’s ideas, but used their words from other sources. He went out of his way to conceal his sources and create the entirely bogus impression of a first-hand interview. (Some people have wondered if his interviews actually took place.) And he used the work of other journalist, from work they had published previously, without acknowledgement.

So how exactly was Hari guilty of plagiarism?

- He quoted other people’s words as if they were his own.

- He didn’t acknowledge his sources.

- He concealed the cut and paste origins of his composition.

A number of his essays and interviews have been analysed, and he has been shown to be guilty of systematic plagiarism. The majority of Internet comments point to the fact that he acted unprofessionally. All his previous work was scrutinised, and it has been suggested that he return the 2008 George Orwell Prize that he was awarded for distinguished reporting.

He began to edit his personal Wikipedia entry, inserting flattering comments on his own work and abilities. But to make matters doubly worse, he then resorted to something even more underhand. Using a false identity (‘David Rose’) he began making pejorative edits to the Wikipedia entries of anybody who had criticised him. When challenged, he denied all this, but was eventually forced to admit the truth and apologise.

Guido Fawkes on the Hari issue and here

Detailed analysis of Hari’s plagiarism

Plagiarism and the Web

32. The World Wide Web has made millions and millions of pages of information available to anybody with access to the Internet. But even though this appears to be ‘free’ – copyright restrictions still apply. If someone writes and publishes a Web page, the copyright belongs to that person.

33. If you wish to use material you have located on the Web, you should acknowledge your sources in the same way that you would material quoted from a printed book.

34. Keep in mind too that information on a Web page might have been put there by someone who does not hold copyright to it.

What follows is the rather strictly-worded code on plagiarism from a typical university handbook.

Plagiarism

Plagiarism is the theft or appropriation of someone else’s work without proper acknowledgement, presenting the materials as if they were one’s own. Plagiarism is a serious academic offence and the consequences are severe.

a) Course work, dissertations, and essays submitted for assessment must be the student’s own work, unless in the case of group projects a joint effort is expected and indicated as such.

b) Unacknowledged direct copying from the work of another person, or the unacknowledged close paraphrasing of somebody else’s work, is called plagiarism and is a serious offence, equated with cheating in examinations. This applies to copying both from other student’s work and from published sources such as books, reports or journal articles.

c) Use of quotations or data from the work of others is entirely acceptable, and is often very valuable provided that the source of the quotation or data is given. Failure to provide a source or put quotation marks around material that is taken from elsewhere gives the appearance that the comments are ostensibly one’s own. When quoting word-for-word from the work of another person quotation marks or indenting (setting the quotation in from the margin) must be used and the source of the quoted material must be acknowledged.

d) Paraphrasing when the original statement is still identifiable and has no acknowledgement, is plagiarism. A close paraphrase of another person’s work must have an acknowledgement to the source. It is not acceptable to put together unacknowledged passages from the same or from different sources link these together with a few words or sentences of your own and changing a few words from the original text: this is regarded as over-dependence on other sources, which is a form of plagiarism.

e) Direct quotation from an earlier piece of the student’s own work, if unattributed, suggests that the work is original, when in fact it is not. The direct copying of one’s own writings qualifies as plagiarism if the fact that the work has been or is to be presented elsewhere is not acknowledged.

f) Sources of quotations used should be listed in full in a bibliography at the end of the piece of work and in a style required by the student’s department.

g) Plagiarism is a serious offence and will always result in imposition of a penalty. In deciding upon the penalty the University will take into account factors such as the year of study, the extent and proportion of the work that has been plagiarised and the apparent intent of the student. the penalties that can be imposed range from a minimum of zero mark for the work (without allowing resubmission) through to downgrading of degree class, the award of a lesser qualification (eg a Pass degree rather than Honours, a certificate rather than a diploma) to disciplinary measures such as suspension or expulsion.

Quoted with the permission of Manchester University

© Roy Johnson 2004

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

At the end of any scholarly writing (an essay, report, or dissertation) you should offer a list of any works you have consulted or from which you have quoted. This list is called a bibliography – literally, a list of books or sources.

At the end of any scholarly writing (an essay, report, or dissertation) you should offer a list of any works you have consulted or from which you have quoted. This list is called a bibliography – literally, a list of books or sources. Good page layout

Good page layout

Confidence

Confidence