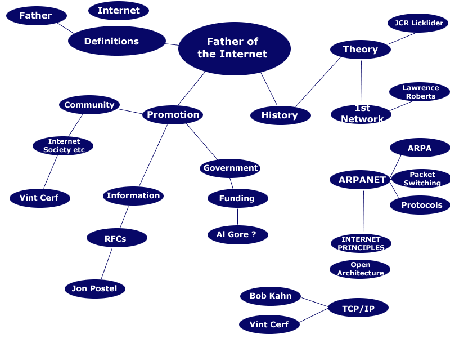

Essay plan as a mind map

Home

Introduction – What is the Internet? – Internet evolution – Father of the Internet

Assignment resources – Essay plan – Definition of terms – Tutor comment

Copyright © James Higginson 2000

Tutorials, Study Guides & More

by Roy Johnson

Copyright © James Higginson 2000

by Roy Johnson

Student: James Higginson

Course: An Introduction to the Internet

WAN

A WAN is a network that covers a large geographical area. Each node in a WAN may be located in a different town. A mainframe or minicomputer will usually be involved somewhere in a WAN.

LAN

A LAN is a network that covers a smaller area than a WAN. Typically a LAN will serve the needs of one institution at one site. For example a university will have their own LAN, as may an individual bank. LANs often connect to other LANs and to WANs to allow communication between them. These interconnected LANs and WANs form a network of networks commonly known as the Internet.

Ethernet

Ethernet is a network protocol for LANs. It operates on a bus network topology. It was developed by Bob Metcalfe at Xerox PARC and is the most popular method of LAN protocol. Its popularity is a result of its reliability, speed and relative cheapness.

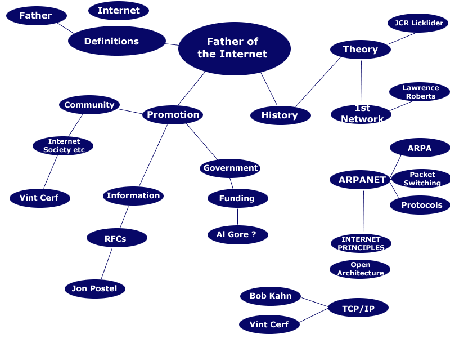

Networks

The public telephone network is officially known as the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN). While switchboard operators were replaced by mechanical, and later by computerized switching equipment, and optical (glass) fibre has replaced much of the copper wiring, the function of the network is still simply to connect the wires of two telephones (or compatible devices such as fax machines or modems), so that sounds coming from one end are transmitted to the other. This is called a ‘circuit-switched’, or more simply ‘switched’, network architecture.

Circuit Switching

While this system is very reliable, it is also extremely inefficient and expensive because the connection is made at the beginning of a conversation, fax transmission, or modem ‘session’, and is maintained until the connection is terminated – meaning a certain portion of the network is reserved exclusively for that conversation whether or not communication is taking place at the moment. If one party puts down the phone or is silent, or neither computer is sending or receiving data for a period of time (as is the case when using the Internet), that circuit as well as the ‘ports’ on the phone switches between the two devices are still unavailable for other activity even though they are not being used at the moment. Since it is estimated that up to 50% of a typical voice conversation is actually silence, clearly a tremendous amount of network capacity is wasted. (Put another way: a company must build double the network it really needs for a given number of simultaneous calls at double the cost.)

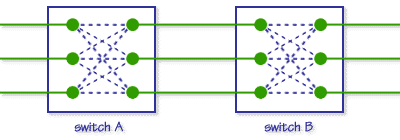

Packet Switching

Packet networks break the digital stream of ones and zeros into chunks of the same length. These chunks, or ‘packets’, are then put in the computer equivalent of an envelope, with some information such as the origin and destination, or ‘addresses’, of the packet, and a serial number that indicates the sequence number of the packet – its ‘place in line’. In the place of switches which merely connect and disconnect circuits, packet networks use routers – computers that read the address of a packet and pass it to another router closer to the destination. At the destination, a few thousandths of a second later, the packets are received, reassembled in the correct order, and converted back into the original message. Here is an illustration of how it works:

Packet Switching – How it works

The routers in a packet-switched network are permanently connected via high-speed lines. This may seem expensive at first sight, but it makes sense economically (and technically) if the network is heavily used, i.e. effectively flooded with packets.

TCP/IP

The Internet works by breaking long messages into smaller chunks called packets which can then be switched through routers until they reach their destinations. The software associated with the TCP/IP family of protocols takes care of the assembly, disassembly and addressing of packets.

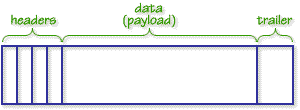

Anatomy of a Packet

Essentially, a packet is a string of bits divided into different segments. At its core is a Data segment (the chunk of the original message) which is sometimes referred to as the payload. In order to arrange for the passage of the payload through the Internet, extra information is added to it in the form of headers or (occasionally) trailers

TCP was eventually split into two protocols – one (IP) to handle addressing of packets, the other (TCP) to deal with their assembly and disassembly. The design philosophy behind this was the belief that it was better to have specialised protocols which each did one job and co-operated with one another rather than trying to design one, all-embracing monolithic protocol which tried to do everything.

DNS

The Domain name system (DNS) is the way that internet domain names are

located and translated into Internet Protocol addressess. A domain name is a

meangingful and easy-to-remember “handle” for an internet address.

POP3

POP3 (Post Office Protocol 3) is the most recent version of a standard protocol for receiving e-mail. POP3 is a client/server protocol in which e-mail is received and held for you by your Internet server. Periodically, you (or your client e-mail receiver) check your mail-box on the server and download any mail. POP3 is built into the Netmanage suite of Internet products and one of the most popular e-mail products, Eudora. It’s also built into the Netscape and Microsoft Internet Explorer browsers.

IMAP

IMAP (Internet Message Access Protocol) is a standard protocol for accessing e-mail from your local server. IMAP (the latest version is IMAP4) is a client/server protocol in which e-mail is received and held for you by your Internet server. You (or your e-mail client) can view just the heading and the sender of the letter and then decide whether to download the mail. You can also create and manipulate folders or mailboxes on the server, delete messages, or search for certain parts or an entire note. IMAP requires continual access to the server during the time that you are working with your mail.

SMTP

SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) is a TCP/IP protocol used in sending and receiving e-mail. However, since it’s limited in its ability to queue messages at the receiving end, it’s usually used with one of two other protocols, POP3 or Internet Message Access Protocol, that let the user save messages in a server mailbox and download them periodically from the server. In other words, users typically use a program that uses SMTP for sending e-mail and either POP3 or IMAP for receiving messages that have been received for them

at their local server.

HTTP

The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the set of rules for exchanging files (text, graphic images, sound, video, and other multimedia files) on the World Wide Web. Relative to the TCP/IP suite of protocol, HTTP is an application protocol. Essential concepts that are part of HTTP include (as its name implies) the idea that files can contain references to other files whose selection will elicit additional transfer requests.

HTML

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is the set of “markup” symbols or codes inserted in a file intended for display on a World Wide Web browser. The markup tells the Web browser how to display a Web page’s words and images for the user.

XML

XML (Extensible Markup Language) is a flexible way to create common information formats and share both the format and the data on the World Wide Web, intranets, and elsewhere. For example, computer makers might agree on a standard or common way to describe the information about a computer product (processor speed, memory size, and so forth) and then describe the product information format with XML. Such a standard way of describing data would enable a user to send an intelligent agent (a program) to each computer maker’s Web site, gather data, and then make a valid comparison. XML can be used by any individual or group of individuals or companies that wants to share information in a consistent way.

Copyright © James Higginson 2000

by Roy Johnson

Student: James Higginson

Course: An Introduction to the Internet

Congratulations on your essay James. It’s a substantial piece of work, and you have done well. I realise that the last few weeks on the course have been tough – and it’s to your credit that you’ve stuck at it.

These are my comments, made as I go through the script. Please bear with me, because I am trying to use the marking software, which is a bit temperamental.

&& – indicates where marks have been gained

** – indicates where marks have been lost

Try to avoid posing your argument in the form of questions. Even if they are answered, they usually have the effect of leading away from the question which has been asked.

Very good that you give full references to all your sources. &&

I liked the definitions of LAN and WAN which you put in as links [which worked well]. This shows your exploiting the potential of HTML. &&

[This is a very small detail] I think the references to your sources might look better as footnotes [with links]. This would leave the web essay itself less ‘cluttered’.

I also liked the fact that you made a well-reasoned attempt to ‘answer the question’ [though I was a little surprised that Donald Davies didn’t get a mention].

Your report/essay is thorough, well-executed, and effective. All the links work, and I liked the way you used the horizontal rule to emphasise the structure.

Your plan is good and shows your clear-thinking skills – &&

Your writing is clear, to-the-point, and ‘objective’ – in just the way which is required for academic work. &&

I am also giving you maximum bonus marks for having emailed Vint Cerf. Even though his reply was too late to go into the web essay, I have seen it in the conference, and I think it is in the spirit of the web that you could add it to your assignment.

You have now completed four essays – which means that there’s only the End of Course Assignment to go. You are heading towards successful completion of the course!

Copyright © James Higginson 2000

by Roy Johnson

Microsoft Word is the world’s most popular word-processor – yet many people never use some of the powerful tools it has to offer. They might jiggle around with a few font choices and toolbar options, but there is a lot more under the bonnet which isn’t immediately apparent. Andrew Savikas’s new book Word Hacks offers tips and guidance for harnessing these hidden strengths. The tips are graded at beginner, moderate, and expert level – so you can work in a way which is comfortable for you. He starts off by telling you how to deal with all the menu options to make Word work as you want it to. Then it’s on to macros – a list of commands which you can store, to save you the problem of boringly repetitive keystrokes and menu choices. He also shows you how to hack your shortcut menus, and how to customise Word.

This ranges from trivial things such as changing the icons and buttons on your toolbars, to getting rid of the annoying and very unpopular Help assistant (Mr Paperclip). He then moves on to more useful tricks such as increasing the number of most recently used files (MRU) listed at the bottom of the File menu, and shows you how to mess with the number of font options available.

This ranges from trivial things such as changing the icons and buttons on your toolbars, to getting rid of the annoying and very unpopular Help assistant (Mr Paperclip). He then moves on to more useful tricks such as increasing the number of most recently used files (MRU) listed at the bottom of the File menu, and shows you how to mess with the number of font options available.

He shows you how to display samples of your fonts instead of just a list of their names; how to create bar graphs using tables; how to repeat a chapter heading across multiple pages; and how to increase the number of styles you can apply to footnotes ands captions.

Most of these tips only require you to type out a short macro (which he supplies) or to hack gently at the regular menu options. Any of the longer procedures are then saved as macros and assigned a keyboard shortcut of your choice.

You’ve probably noticed that Web addresses typed in Word turn automatically into hyperlinks – underlined and coloured blue. For those people (like me) who find this annoying, he shows you how to change the appearance and even get rid of them.

For serious and industrial strength writing he shows you how to do powerful search and replace edits, how to add custom (and temporary) dictionaries for special projects, how to take control of the way Word deals with bulleted lists, and how to make the most out of Word’s outlining feature.

There’s a whole chapter devoted to troubleshooting common Word problems – such as missing toolbars, repeated freezes and crashes, and the proliferation of unwanted temporary files. Then he finishes with some fairly advanced suggestions on forms and fields, plus how to get Word to perform calculations using tables, and using Word to work in XML and XSLT.

My guess is that this is one for people who like Word, who are committed to staying with it, and who want to get more from it in terms of power and productivity. It will also be useful to writers and editors working on book-length projects and reports. As usual with O’Reilly publications, the layout and presentation are impeccable.

© Roy Johnson 2004

Andrew Savikas, Word Hacks: Tips and Tools for Taming your Text, Sebastapol: CA, 2004, pp.372, ISBN: 0596004931

by Roy Johnson

1. You should make every effort to stay within any word limits that have been set for an essay assignment. One important part of the exercise is that you should produce an answer to the question within set limits.

2. You will not normally be penalised if your essay is a little too short – so long as your argument is written in a concise style and you have covered all the topics which a full answer requires.

3. Similarly, an essay that is just slightly too long will not normally be penalised – so long as all your arguments are relevant to the point of the question.

4. However, you should avoid producing essays which greatly exceed the word limit. The longer you go on writing, the more likely you are to stray away from the point of the question. You will not normally be rewarded just for the quantity you produce.

5. An essay which seriously exceeds the word limit (say, by more than twenty or thirty percent) could be returned to you by your tutor as unacceptable. The argument could be made that you are not staying within the set limits, and you are possibly taking an unfair advantage over other students who have stayed within them.

6. Quotations should not normally be counted as part of the word limit – but the total amount of material from secondary sources should be so small that the proportion is insignificant.

7. You do not need to make a detailed count of every word (or pencil totals in the margin as ‘proof’). Use the word-count feature of

your word-processor to get an idea of the total. If it doesn’t have a counter, just make the following calculation for a rough estimate of your total word count:

words per line × lines per page × pages

8. If an essay is too long before you produce your final draft, its length may be reduced by rigorous editing. Consider some of the following possibilities.

9. Eliminate any repetitions in your basic argument. If you cover the same point from more than one perspective, retain only the most important parts of the discussion, and delete the others.

10. You might consider shortening your introduction, certainly if goes on for much more than 200 words. In some extreme cases it might even be better to go straight to your argument.

11. Check your prose style and try to make the expression of your argument as concise as possible. If necessary, shorten the length of your sentences by removing any words which are not essential to the argument. Cut out anything which introduces a conversational tone.

12. Reduce the number of illustrative examples. Each major point of your argument should normally be illustrated by one or [at the most] two examples of evidence which are then analysed or discussed. If you have more, you should just retain the most convincing and relevant. Eliminate the others.

13. Shorten any illustrative quotations to the absolute minimum. Most essays should not need long quotations from secondary sources – if only because it is your own argument which is more important. Select just those few words which make your point.

14. If on the other hand your final efforts have produced an essay which is shorter than the required length, you obviously need to do some extra work on it. Consider the following steps.

15. Go back to the start of the essay planning process and generate more ideas and topics on the subject in question. Try to think of new approaches or aspects of the subject which you might have ignored or forgotten.

15. Look closely at the question again. Ask yourself if you have followed all its instructions and covered all that it has asked for.

16. Make sure that you have provided an explanatory introduction and conclusion to the essay. Don’t waffle just for the sake of filling up the space. Introduce your argument succinctly and make sure that you have explained its relevance to the original question.

17. It might be that you have produced an argument which is not well enough illustrated by examples which are analysed and discussed. Make sure that you have sufficient evidence and explanatory examples to prove your point. Do not let an argument stand alone without proof.

18. Make sure that you have explained the relevance of your argument to the question which was originally posed. In other words, you must demonstrate the connection between your examples and the subject in question.

© Roy Johnson 2003

Buy Writing Essays — eBook in PDF format

Buy Writing Essays 3.0 — eBook in HTML format

by Roy Johnson

1. The advantages of using word-processors for writing essays are overwhelming. They offer editing and re-writing tools, spelling-checkers and grammar-checkers, plus many features for improved layout and presentation.

2. If you are only just starting to use a word-processor and still producing handwritten essays, don’t feel disadvantaged. Keep in mind however (as an encouragement) that as presentation standards are forced up by word-processors, tutors are likely to become less and less tolerant of untidy work.

3. The main advantage of a computer when writing essays is that it allows you unlimited scope for re-writing and editing what you produce. You may start out with only a sketchy outline, but to this you can add extra examples, delete mistakes, and move paragraphs around to improve your argument. You are able to build up to the finished product in as many stages as you wish.

4. At first you might continue to produce your first draft in handwritten form, then transfer it into your computer at the keyboard. You can then edit what you have written, either on screen or by printing out what you have produced. This is quite common for beginners.

5. You will probably feel a strong desire to see everything printed out as soon as possible. Later however, with experience, you might edit on screen, only printing out the finished version. Most recent word-processors allow you to see on screen what the finished document will look like.

6. Before you print out your final document, make sure to leave plenty of blank space around the text so that your tutor can write detailed comments on what you have produced. Take the trouble to set wide margins, and follow the guidelines for good page layout and presentation.

7. The word-processor will produce your documents very neatly, but will probably do so by using single line spacing. Even though you are likely to be pleased by the neatness, learn how to set for one-and-a-half or double spacing so that your tutor is still able to make helpful additions and corrections between the lines of text.

8. If your word-processor has a spell-checking facility, then use it before you print out your document. But remember that it is unlikely to recognise specialist terms and unusual names such as ‘Schumacher’, ‘Derrida’, or ‘Nabokov’. These will not be in the processor’s memory. You will have to check the correct spelling of these yourself, as you will any other unusual words.

9. Remember too that a spell-checker will not make any distinction between ‘They washed their own clothes’ and ‘They washed there own clothes’, because the word ‘there’ is spelled correctly even though it is being used ungrammatically in this sentence. Use your grammar-checker [if you have one] to locate such problems.

10. Use italics to indicate the titles of books. (Reserve bold for special emphasis.) It is important that you are consistent throughout your document.

A.J.P. Taylor, The Origins of the Second World War, London: Penguin, 1987.

11. Take full advantage of indenting to regularise your presentation of quotations. Use double indentation for those longer quotations which would otherwise occupy more than two or three lines of the text in your essay. Try to be consistent throughout.

12. Advanced users may well be tempted to take advantage of automatic footnoting. Word-processors can remove all the headaches from this procedure. However, do not clutter your text with them just for the sake of showing off your command of the technology.

13. In most cases, the size of font chosen should be eleven or twelve points. This will be easy to read, and will appear proportionate to its use, when printed out on A4 paper.

14. Choose a font with serifs (such as ‘Times New Roman’ or ‘Garamond’) for the body of an essay text. Avoid the use of sans-serif fonts (such as ‘Arial’ or ‘Helvetica’): these make reading difficult. Avoid using display fonts (such as ‘Poster’ or ‘Showtime’) altogether. These are designed for advertising.

15. Long quotations (where necessary) should normally be set in the same font as the body of the text, but the size may be reduced by one or two points. This draws attention to the fact that it is a quotation from a secondary source. Alternatively (or in addition) it may be set in a slightly different font.

16. If your word-processor automatically hyphenates words at the end of a line, take care to read through the work and eliminate any howlers such as ‘the-rapist’ and ‘thin-king’.

17. In laying out your pages, you should avoid creating paragraphs which start on the last line of a page or which finish on the first of the next. (These are called, in the jargon of the printing trade, ‘Widows and Orphans’). The solution to this problem is to control the number of lines on a page so as to push the text forward. An extra space at the bottom of a page is more acceptable than just one or two lines of text at the top of the next.

18. Titles, main headings, or essay questions may be presented in either a slightly larger font size than the body of the text, or they may be given emphasis by the use of bold.

19. Don’t use continuous capital letters in a title, heading, or question. In addition [even though many people think it is good practice] there should be no need at all to underline. If something is a title, a heading or a question at the top of an essay, then the larger font, and the use of bold should be enough to give it emphasis and importance.

20. Don’t forget to put your name and student ID number on any work you submit.

© Roy Johnson 2003

Buy Writing Essays — eBook in PDF format

Buy Writing Essays 3.0 — eBook in HTML format

by Roy Johnson

Write in Style is a good-natured and humane guide to the main elements of producing fluent and accurate English. Richard Palmer’s approach is practical and refreshingly irreverent. He covers good and bad sentences; how to deal with punctuation; how to strike the right tone; and the rules of spelling and grammar – plus all the bewildering exceptions to them. His pace is leisurely and the style conversational. He’s particularly good at explaining the problems and irregularities of the English language. Every point is illustrated with vivid examples – gaffes from the popular press and good style from skilful authors.

He covers all the fundamentals and issues which commonly give people problems – such as the differences between clauses, phrases, and complete sentences. There are also exercises (with answers) at the end of each chapter, so that you can check your understanding of each topic.

He covers all the fundamentals and issues which commonly give people problems – such as the differences between clauses, phrases, and complete sentences. There are also exercises (with answers) at the end of each chapter, so that you can check your understanding of each topic.

All the common marks of punctuation are fully explained, including the much-misunderstood apostrophe. There’s a whole chapter devoted to advice on writing academic essays – a very good discipline to acquire for anybody who wants to develop their writing skills. Then he does the same thing for reports, reviews, and the quite tricky precis and summary.

This will appeal to people who want to be taken by the hand and led through the complexities of English by a reassuring teacher. The strength of this book is that every point is thoroughly explained and illustrated by good and bad examples – many of them very amusing.

© Roy Johnson 2003

Richard Palmer, Write in Style: a guide to good English, London: Routledge, 2nd edn, 2002, pp.255, ISBN: 0415252636

More on writing skills

More on language

More on grammar

by Roy Johnson

1. Writer’s block is much more common than many people imagine. When faced with the task of producing a piece of writing, many people develop a mental block. It can be like a state of panic, emptiness, paralysis – or just a sheer inability to get started. You simply cannot make the pen move across the page or type the words at the keyboard. After agonizing for a while you might just squeeze out a few words, but then immediately delete them again – and you are back where you started.

2. Suddenly all sorts of other tasks seem very attractive – going shopping, or just taking the dog for a walk. You desperately want to write your essay or report, and you may even have a deadline to meet. But the last thing you can bring yourself to do is start writing. And the longer you worry about it, the more intractable the problem seems to become.

3. If you sometimes feel like this, here is the first piece of good news. It is a very common problem. Even experienced writers sometimes suffer from it. Do not think that you are the only person in the world who has ever encountered such a difficulty. What you need to know is how to get out of the blocked condition.

4. Most people read as part of their everyday lives, even if it is only glancing through newspapers and the occasional magazine. In doing so they keep their reading skills sharpened. Some of them may even develop it further by an active habit of reading. However, there are a lot of people who have hardly any need to write at all, and this skill is allowed to go rusty or even wither away. They simply become out of practice.

5. There are also a series of other possible reasons – many of them psychological in origin. Others may be connected with simple factors such as lack of preparation, or the common but rather misguided assumption that it is possible to write successfully at the first attempt.

6. The notes which follow are a series of the most common statements made by people suffering from writer’s block. This should help you identify your own case if you have this problem. Then there follow explanations of one or two of the most probable causes for the condition – followed by tips on how to effect a cure.

7. Read through all the examples given. It will help you to understand that overcoming writer’s block often involves engagement with those other parts of the writing process which come before you put pen to paper.

1. ‘ I’m terrified at the very thought of writing’

Cause – Perhaps you are just not used to writing, or you are out of recent practice. Maybe you are over-anxious and possibly setting yourself standards which are far too high.

Cure – Limber up and get yourself used to the activity of writing by scribbling something on a scrap of paper or keying in a few words which nobody else will see. Write a letter to yourself, a description of the room you are in – anything just to practise getting words onto paper. Remember that your attempts can be discarded. They are a means to an end, not a product to be retained.

2. ‘I’m not sure what to say‘

Cause – Maybe you have not done enough preparation for the task in hand, and you don’t have any notes to work from and use as a basis for what you want to say. Perhaps you haven’t yet accumulated enough ideas, comments, or materials on the topic you are supposed to be discussing. Possibly you have not thought about the subject for long enough.

Cure – Sort out your ideas before you start writing. Make rough notes on the topics you wish to discuss. These can then be expanded when you are ready to begin. Brainstorm you topic; read about it; put all your preliminary ideas on rough paper, then sift out the best for a working plan. Alternatively, make a start with anything, then be prepared to change it later.

3. ‘My mind goes blank’

Cause – Maybe you have not done enough preparation on the topic in question and you are therefore short of ideas or arguments. Perhaps you do not have rough notes or a working plan to help you formulate a response. Maybe you are frightened of making a false start or saying the wrong thing.

Cure – Make notes for what you intend to do and sort out your ideas in outline first. Try starting yourself off on some scrap paper or a blank screen. You can practise your opening statement and then discard it once you are started. Put down anything that comes into your head. You can always cross it out or change it later.

4. ‘It’s just a problem of the first sentence’

Cause – These can be quite hard to write! There is quite a skill in striking the right note immediately. You may be thinking ‘How can I make an introduction to something which I have not yet written?’ Maybe you have not created a plan and do not therefore know what will follow any opening statement you make. Perhaps you are setting yourself standards which are much too high or unrealistic. Maybe you are fixated on the order of your statements – or just possibly using this as an excuse to put off the moment when you will have to start.

Cure – Leave a blank space at the beginning of what you are going to write. The first sentence can be written later after you have finished the rest. Make a start somewhere else and come back to it later. Alternatively, write any statement you wish, knowing that you will change it later.

5. ‘I’m not quite ready to start yet‘

Cause – This could be procrastination, or it’s possible that you have not quite finished digesting and sorting out your ideas on the topic in question.

Cure – If it is procrastination, then use the warming up procedure of writing something else of no importance just to get yourself into the mood. If it is not, then maybe you need to revise your notes, drum up a few more ideas, or make a working plan to give you a point from which to make a start.

6. ‘I’ve got too much information’

Cause – If you have several pages of notes, then maybe they need to be digested further. Maybe you have not selected the details which are most important, and eliminated anything which is not relevant.

Cure – Digest and edit your material so as to pare it down to what is most essential. Several pages of notes may need to be reduced to just one or two. Don’t try to include everything. Draw up a plan that includes only indispensable items. If your plan is too long, then condense it. Eliminate anything that is not absolutely necessary for the piece of work in hand.

7. ‘I’m just waiting for one small piece of information’

Cause – Maybe you feel that a crucial piece of background reading – a name, or just a date is holding you up. You may be waiting for a book to be returned to the library. But this is often another form of procrastination – making excuses so as not to face the task in hand.

Cure – Make a start without it anyway. You can always leave gaps in your work and add things later. Alternatively, make a calculated guess – which you can change if necessary at a later stage when you have acquired the missing information. Remember that your first draftwill be revised later anyway. Additional pieces of information can be added during the editing process.

8. ‘I’m frightened of producing rubbish’

Cause – Maybe you are being too hard on yourself and setting standards which are unnecessarily high. However, this can sometimes be an odd form of pride, with which some people protect themselves from what they see as the embarrassment of having to go through the process of learning.

Cure – Be prepared to accept a modest achievement at first. And remember that many people under-rate their potential ability. It is very unlikely that anybody else will be over-critical. If you are a student on a course, it is the tutor’s job to help you improve and become more confident.

9. ‘I’m stuck at the planning stage’

Cause – This may be a hidden fear of starting work on the first draft, or it may possibly be a form of perfectionism. It may be that you are making too much of the planning stages, or alternatively that you are stuck for ideas.

Cure – Make a start on the first draft anyway. You can create a first attempt which may even help you to clarify your ideas as you are writing it. This first draft may then be used to help you devise and finalise another plan – which can then be used as the basis for your second or final draft.

10. ‘I’m not sure in what order to put things’

Cause – Maybe there are a number of possibilities, and you are seeking the best order. Perhaps there is no ‘best’ or ‘right’ order. You are probably looking for some coherence or logical plan for your ideas.

Cure – Draw up a number of different possible plans. Lay them out together, compare them, then select the one which seems to offer the best structure. Be prepared to chop and change the order of your information until the most persuasive form of organisation emerges. Make sure that you do this before you start writing, so that you are not trying to solve too many problems at the same time once you begin.

11. ‘It’s bound to contain a mistake somewhere’

Cause – You may be so anxious to produce good work that your fear of making a mistake is producing the ‘block’. Alternatively, this may be a form of striving for the impossible, or setting yourself unreachably high goals so as to create an excuse for not starting.

Cure – Your first efforts should only be a draft, so you can check for mistakes at a later stage. Be prepared to make a start, then deal with any possible errors when you come to re-write the work later. Very few people can write without making mistakes – even professional authors – so there is no need to burden yourself with this block.

Some general guidelines

© Roy Johnson 2003

Buy Writing Essays — eBook in PDF format

Buy Writing Essays 3.0 — eBook in HTML format

More on writing essays

More on How-To

More on writing skills

by Roy Johnson

The best-selling guide to marketing your writing so far is The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, with The Writer’s Handbook a close second. But there’s always room for competition in an open market – and Writer’s Market UK is competition writ large. It’s a huge, 1,000 page compendium of advice, resources, and detailed information on how writers can locate markets and get their work into print. The format for these books is now fairly standardised.

They have feature articles written by well-known authors giving advice on breaking into print. These are surrounded by listings of publishers, magazines, literary agents, and broadcast outlets. Then come specialized resources such as prizes and competitions, bursaries and fellowships, writers groups, and web sites.

They have feature articles written by well-known authors giving advice on breaking into print. These are surrounded by listings of publishers, magazines, literary agents, and broadcast outlets. Then come specialized resources such as prizes and competitions, bursaries and fellowships, writers groups, and web sites.

The usefulness of this information relies on its being accurate, up-to-date, and annotated to explain the nuances and differences between one source and the next. In other words, the compilers need to know what they’re talking about. This book scores well on all counts, and the editor Caroline Taggart has done a good job.

For instance, the feature articles are precisely the sort of advice that aspirant writers are most likely to want and need. How to tackle the various genres of fiction writing: the short story, children’s writing, crime, and the novel. What agents and publishers are looking for – and how to approach them. Writing for radio, the Web, newspapers and magazines are all covered well,

There are essays on how books are designed, financed, and marketed, plus why you should know about contracts and legal issues. There are articles on the odd but very profitable field of ghost writing, and when you have made lots of money how to deal with agents, and how to promote your work once it’s published.

There are huge listings of bursaries, prizes, competitions, writers’ foundations, and all sorts of support to help the struggling want-to-be. And testing it out for being up to date, I found all sorts of on line resources for would-be writers: magazines, forums, self-help groups, web sites full of resources, writing software, plus competitions and prizes.

Given the differences in page and font sizes, it’s difficult to do a direct quantitative comparison with its two main rivals, but having looked through all three recently, I’d say that this gives the other two a very good run for their money.

© Roy Johnson 2003

Caroline Taggart (ed), Writer’s Market UK, London: David & Charles, issued annually, pp.976, ISBN: 0715332856

More on creative writing

More on writing skills

More on publishing

by Roy Johnson

If you’ve just finished producing your masterpiece, this writer’s yearbook will help you to bring it to the marketplace. It’s a well-established reference guide for writers, journalists, photographers, and other people in the creative arts. The heart of the book is its amazingly comprehensive listings. It offers full contact details of publishers, agents, and institutions who deal with writers and creative arts people. The lists cover the UK and US, as well as other English-speaking countries.

In recent years, short essays have been added to each section offering advice to would-be writers and media workers. Pay attention to these: they’re written by professionals with experience and a proven track record. The information they offer will repay the price of the book ten times over. They cover fiction and poetry; drama scripts for TV, radio, theatre, and film; graphic illustration and design; plus photography and music. The other features which make it useful are general information on publishing methods, copyright and libel, income tax and allowances, and a particularly useful list of annual competitions and their prizes.

In recent years, short essays have been added to each section offering advice to would-be writers and media workers. Pay attention to these: they’re written by professionals with experience and a proven track record. The information they offer will repay the price of the book ten times over. They cover fiction and poetry; drama scripts for TV, radio, theatre, and film; graphic illustration and design; plus photography and music. The other features which make it useful are general information on publishing methods, copyright and libel, income tax and allowances, and a particularly useful list of annual competitions and their prizes.

Bonus items seem to be added with each edition – such as a list of the highest earning books of the previous year, specialist literary agents, how to prepare and submit a manuscript, and even (if the worst comes to the worst) how to claim social security benefits. The latest edition also includes sections on e-publishing, ghostwriting, distribution, adaptation, and digital imaging.

Additions to the latest edition include: Self-publishing; How to publicise your book; How to get an agent’s attention: Getting cartoons published; Blogging; Crime writing; and Can you recommend an agent?

Like many other reference books, it represents very good value for money in terms of bulk information – but more importantly it’s information which is reliable, up-to-date, and difficult to locate elsewhere.

If you have any serious intention of entering the commercial market as a writer or someone working in one of the other creative arts – then this is a book which you will need sooner or later. It’s no wonder that it sits near the top of the Amazon ratings all the year round.

© Roy Johnson 2012

Writers’ & Artists’ Yearbook, London: A & C Black (issued annually) pp.816, ISBN: 1408192195

More on creative writing

More on writing skills

More on publishing