tutorial and guide to important texts

The short story is as old as the earliest tale-telling. Many longer narratives such as epics and myths (such as the Bible) contain short episodes which can be extracted as stories. But as a distinct literary genre, the short story came into its own during the early nineteenth century. Many writers have created successful short stories – but those which follow are the prose artists who have had most influence on its development in terms of form. We will be adding more guidance notes and examples as time goes on.

Edgar Allen Poe is famous for his Tales of Mystery and Imagination. These are tight, beautifully crafted exercises in plot, suspense, psychological drama, and sheer horror. He also invented the detective story. This is the birth of the modern short story. Poe was writing for magazines and journals. He has a spectacularly florid style, and his settings of dungeons and crumbling houses come straight out of the Gothic tradition. He’s most famous for stories such as ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’, ‘The Black Cat’, and ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ which vividly dramatise extreme states of psychological terror, anxiety, and what we would now call existential threat. He also theorised about the story, claiming that every part should be contributing to the whole, and the story should be short enough to read at one sitting. This edition is good because it includes the best of the stories, plus some essays and reviews. An ideal starting point.

Edgar Allen Poe is famous for his Tales of Mystery and Imagination. These are tight, beautifully crafted exercises in plot, suspense, psychological drama, and sheer horror. He also invented the detective story. This is the birth of the modern short story. Poe was writing for magazines and journals. He has a spectacularly florid style, and his settings of dungeons and crumbling houses come straight out of the Gothic tradition. He’s most famous for stories such as ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’, ‘The Black Cat’, and ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ which vividly dramatise extreme states of psychological terror, anxiety, and what we would now call existential threat. He also theorised about the story, claiming that every part should be contributing to the whole, and the story should be short enough to read at one sitting. This edition is good because it includes the best of the stories, plus some essays and reviews. An ideal starting point.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

How short is short?

There is no fixed length for a short story. Readers generally expect a character, an event of some kind, and a sense of resolution. But Virginia Woolf got most of this in to one page in her experimental short story Monday or Tuesday. There are also ‘abrupt fictions’ of a paragraph or two – but these tend to be not much more than anecdotes.

There’s an often recounted anecdote regarding a competition for the shortest possible short story. It was won by Ernest Hemingway with an entry of one sentence in six words: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”

There are also quite long stories – such as those written by Henry James. If the narrative sticks to one character and one issue or episode, they remain stories. If they stray into greater degrees of complexity and develop expanded themes and dense structure – then they often become novellas. Examples of these include Herman Melville’s Billy Budd, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice.

Nathaniel Hawthorne produced stories that are beautifully crafted studies in symbolism, moral ambiguity, and metaphors of the American psyche. His tales are full of characters oppressed by consciousness of sin, guilt, and retribution. They explore the traditions and the consequences of the Puritanism Europe exported to America. Young Goodman Brown and Other Stories in the Oxford University Press edition presents twenty of Hawthorne’s best tales. It’s the first in paperback to offer his most important short works with full annotation in one volume.

Nathaniel Hawthorne produced stories that are beautifully crafted studies in symbolism, moral ambiguity, and metaphors of the American psyche. His tales are full of characters oppressed by consciousness of sin, guilt, and retribution. They explore the traditions and the consequences of the Puritanism Europe exported to America. Young Goodman Brown and Other Stories in the Oxford University Press edition presents twenty of Hawthorne’s best tales. It’s the first in paperback to offer his most important short works with full annotation in one volume.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

Guy de Maupassant brought the subject matter of the story down to an everyday level which shocked readers at the time – and can still do so now. He also began to downgrade the element of plot and suspense in favour of character revelation. He was a relative of Flaubert, a novelist manqué, and bon viveur who died at forty-three of syphilis in a madhouse. Nevertheless he left behind him an oeuvre of more than 300 stories. His tone is objective, detached, and often deeply ironic; and he is celebrated for the exactness and accuracy of his observations, and the balance and precision of his style. Although most of his stories appear at first to be nothing more than brief and rather transparent anecdotes, the best succeed in giving impressionistic but truthful insights into the hidden lives of people caught amidst the trials of everyday existence.

Guy de Maupassant brought the subject matter of the story down to an everyday level which shocked readers at the time – and can still do so now. He also began to downgrade the element of plot and suspense in favour of character revelation. He was a relative of Flaubert, a novelist manqué, and bon viveur who died at forty-three of syphilis in a madhouse. Nevertheless he left behind him an oeuvre of more than 300 stories. His tone is objective, detached, and often deeply ironic; and he is celebrated for the exactness and accuracy of his observations, and the balance and precision of his style. Although most of his stories appear at first to be nothing more than brief and rather transparent anecdotes, the best succeed in giving impressionistic but truthful insights into the hidden lives of people caught amidst the trials of everyday existence.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

Charles E. May, The Short Story: the reality of artifice, London: Routledge, 2002, pp.160, ISBN 041593883X. This is a study of the development of the short story as a literary genre – from its origins to the present day. It takes in most of the major figures – Poe, Hawthorn, James, Conrad, Hemingway, Borges, and Cheever. There’s also a very useful chronology, giving dates of significant publications, full notes and references. and annotated suggestions for further reading. Despite the obvious US weighting here, for anyone who needs an overview of the short story and an insight into how stories are analysed as part of undergraduate studies, this is an excellent place to start.

Charles E. May, The Short Story: the reality of artifice, London: Routledge, 2002, pp.160, ISBN 041593883X. This is a study of the development of the short story as a literary genre – from its origins to the present day. It takes in most of the major figures – Poe, Hawthorn, James, Conrad, Hemingway, Borges, and Cheever. There’s also a very useful chronology, giving dates of significant publications, full notes and references. and annotated suggestions for further reading. Despite the obvious US weighting here, for anyone who needs an overview of the short story and an insight into how stories are analysed as part of undergraduate studies, this is an excellent place to start.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

Katherine Mansfield is one of the few major writers who worked entirely within the short story form. Her finest work is available in just one volume. She followed Chekhov in paring down the dramatic element of the short story to a minimum, whilst raising its level of subtlety and psychological insight to new heights. Every smallest detail within her stories is carefully chosen to complete a pattern which the whole tale symbolises. She was also an early feminist in presenting many of her stories from a convincingly radical point of view. In this she was rather like her friend and contemporary, Virginia Woolf with whom she discussed the new literary techniques they were both developing at the same time. Unfortunately, Katherine Mansfield died at only thirty-five when she was at the height of her powers.

Katherine Mansfield is one of the few major writers who worked entirely within the short story form. Her finest work is available in just one volume. She followed Chekhov in paring down the dramatic element of the short story to a minimum, whilst raising its level of subtlety and psychological insight to new heights. Every smallest detail within her stories is carefully chosen to complete a pattern which the whole tale symbolises. She was also an early feminist in presenting many of her stories from a convincingly radical point of view. In this she was rather like her friend and contemporary, Virginia Woolf with whom she discussed the new literary techniques they were both developing at the same time. Unfortunately, Katherine Mansfield died at only thirty-five when she was at the height of her powers.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

James Joyce published Dubliners in 1916 and established himself immediately as a great writer. This has been an enormously influential collection which helped to establish the form of the modern short story. These are studies of Dublin life and characters written in a stark, pared-down style. Most of the characters and scenes are mean and petty – sometimes even tragic. Joyce had difficulty finding a publisher for this his first book, and it did not appear until many years after it had been written. It was severely attacked because the names of actual persons and places in Dublin are mentioned in it. Several of the characters introduced in Dubliners eventually reappear in his great novel Ulysses. In terms of literary technique, Joyce is best known for his use of the ‘epiphany’ – the revealing moment or experience used as a focal point for the purpose of the story.

James Joyce published Dubliners in 1916 and established himself immediately as a great writer. This has been an enormously influential collection which helped to establish the form of the modern short story. These are studies of Dublin life and characters written in a stark, pared-down style. Most of the characters and scenes are mean and petty – sometimes even tragic. Joyce had difficulty finding a publisher for this his first book, and it did not appear until many years after it had been written. It was severely attacked because the names of actual persons and places in Dublin are mentioned in it. Several of the characters introduced in Dubliners eventually reappear in his great novel Ulysses. In terms of literary technique, Joyce is best known for his use of the ‘epiphany’ – the revealing moment or experience used as a focal point for the purpose of the story.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Whiplash Ending

It used to be thought that the ‘point’ of a short story was best held back until the last paragraph. The idea was that the reader was being entertained – and then suddenly surprised by a revelation or an unexpected reversal or twist. O. Henry popularised this device in the US. However, most serious modern writers after Chekhov came to think that this was rather a cheap strategy. They proposed instead the relatively eventless story which presents a situation that unfolds itself to the reader for contemplation.

Virginia Woolf took the short story as it had come to be developed post-Chekhov, and with it she blended the prose poem, poetic meditations, and the plotless event. Her finest achievements in this form – Kew Gardens, Sunday or Monday, and The Lady in the Looking-glass‘ – create new linguistic worlds without the prop of a story line. These offer a poetic evocation of life and meditations on time, memory, and death. This edition contains all the classic short stories such as The Mark on the Wall, A Haunted House, and The String Quartet – but also the shorter fragments and experimental pieces such as Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street. These ‘sketches’ (as she called them) were used to practice the techniques she used in her longer fictions. Nearly fifty pieces written over the course of Woolf’s writing career are arranged chronologically to offer insights into her development as a writer. This is well presented and edited in a scholarly manner by Susan Dick.

Virginia Woolf took the short story as it had come to be developed post-Chekhov, and with it she blended the prose poem, poetic meditations, and the plotless event. Her finest achievements in this form – Kew Gardens, Sunday or Monday, and The Lady in the Looking-glass‘ – create new linguistic worlds without the prop of a story line. These offer a poetic evocation of life and meditations on time, memory, and death. This edition contains all the classic short stories such as The Mark on the Wall, A Haunted House, and The String Quartet – but also the shorter fragments and experimental pieces such as Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street. These ‘sketches’ (as she called them) were used to practice the techniques she used in her longer fictions. Nearly fifty pieces written over the course of Woolf’s writing career are arranged chronologically to offer insights into her development as a writer. This is well presented and edited in a scholarly manner by Susan Dick.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

Franz Kafka created stories and ‘fragments’ (as he called them) which are a strange, often nightmarish mixture of tale and philosophic meditation. Start with Metamorphosis – the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s first publication – a slim volume of what he called ‘Meditations’ – as well as the forty-page ‘Letter to his Father’. It also contains the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’. Kafka is famous for having anticipated in his work many of the modern states of psychological angst, alienation, and existential terror which became commonplace later in the century.

Franz Kafka created stories and ‘fragments’ (as he called them) which are a strange, often nightmarish mixture of tale and philosophic meditation. Start with Metamorphosis – the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s first publication – a slim volume of what he called ‘Meditations’ – as well as the forty-page ‘Letter to his Father’. It also contains the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’. Kafka is famous for having anticipated in his work many of the modern states of psychological angst, alienation, and existential terror which became commonplace later in the century.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

Epiphanies and Moments

James Joyce’s contribution to the short story was a device he called the ‘epiphany’. Following Guy de Maupassant and Chekhov, he wrote the series of stories Dubliners which were pared down in terms of literary style and focussed their effect on a revelation. A sudden remark, a symbol, or moment epitomises and clarifies the meaning of a complex experience. This usually comes at the end of the story – either for the character in the story or for the reader. Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf followed a similar route of playing down action and events in favour of dramatising insights into character and states of mind. Woolf called these ‘moments of being’.

Jorge Luis Borges like Katherine Mansfield, only wrote short stories. He was an Argentinian, much influenced by English Literature. His tales manage to combine literary playfulness and a rich style with strange explorations of mind-bending ideas. He is credited as one of the fathers of magical realism, which is one feature of Latin-American literature which has spread worldwide since the 1960s. His stories often start in a concrete, realistic world then gradually slide into strange dreamlike states and end up leaving you to wonder where on earth you are, and how you got there. Funes, the Memorious explores the idea of a man who cannot forget anything; The Garden of Forking Paths is a marvellous double-take on the detective story; and Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius is a pseudo-essay concerning encyclopedia entries of an imaginary world – which begin to invade and multiply within our own. He also wrote some rather amusing literary spoofs, which are collected in this edition.

Jorge Luis Borges like Katherine Mansfield, only wrote short stories. He was an Argentinian, much influenced by English Literature. His tales manage to combine literary playfulness and a rich style with strange explorations of mind-bending ideas. He is credited as one of the fathers of magical realism, which is one feature of Latin-American literature which has spread worldwide since the 1960s. His stories often start in a concrete, realistic world then gradually slide into strange dreamlike states and end up leaving you to wonder where on earth you are, and how you got there. Funes, the Memorious explores the idea of a man who cannot forget anything; The Garden of Forking Paths is a marvellous double-take on the detective story; and Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius is a pseudo-essay concerning encyclopedia entries of an imaginary world – which begin to invade and multiply within our own. He also wrote some rather amusing literary spoofs, which are collected in this edition.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

Ernest Hemingway trained as a newspaper reporter and began writing short stories in the post-Chekhov period, consciously influenced by his admiration for the Russian novelist Turgenev. He is celebrated for his terseness and understatement – a sort of literary tough-guy style which was much imitated at one time His persistent themes are physical and moral courage, stoicism, and what he called ‘grace under pressure’. Because his stories are so pared to the bone, free of all superfluous decoration, and so reliant on the closely observed detail, they fit well within the modernist style. He once won a bet that he could write a short story in six words. The result was – ‘For sale: baby shoes. Never worn.’ His reputation as a novelist has plummeted recently, but his stories are still worth reading.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

John Cheever is a story writer in the smooth and sophisticated New Yorker school. His writing is urbane, thoughtful, and his social details well observed. What he writes about are the small moments of enlightenment which lie waiting in everyday life, as well as the smouldering vices which lurk beneath the polite surface of suburban America. This is no doubt a reflection of Cheever’s own experience. For many years as a successful writer and family man he was also an alcoholic and led a secret double life as a homosexual. His main themes include the duality of human nature: sometimes dramatized as the disparity between a character’s decorous social persona and inner corruption. His is a literary approach which has given rise to many imitators, perhaps the best known of whom is Anne Tyler. He’s sometimes called ‘the Checkhov of the suburbs’.

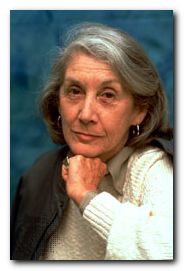

Nadine Gordimer is one of the few modern writers who have developed the short story as a literary genre beyond what Virginia Woolf pushed it to in the early modernist phase. She starts off in modern post-Chekhovian mode presenting situations which have little drama but which invite the reader to contemplate states of being or moods which illustrate the ideologies of South Africa. Technically, she experiments heavily with point of view, narrative perspective, unexplained incidents, switches between internal monologue and third person narrative and a heavy use of ‘as if’ prose where narrator-author boundaries become very blurred. Some of her stories became more lyrical, more compacted and symbolic, abandoning any semblance of conventional story or plot in favour of a poetic meditation on a theme. All of this can make enormous demands upon the reader. Sometimes, on first reading, it’s even hard to know what is going on. But gradually a densely concentrated image or an idea will emerge – the equivalent of a Joycean ‘epiphany’ – and everything falls into place. Her own collection of Selected Stories are UK National Curriculum recommended reading.

Nadine Gordimer is one of the few modern writers who have developed the short story as a literary genre beyond what Virginia Woolf pushed it to in the early modernist phase. She starts off in modern post-Chekhovian mode presenting situations which have little drama but which invite the reader to contemplate states of being or moods which illustrate the ideologies of South Africa. Technically, she experiments heavily with point of view, narrative perspective, unexplained incidents, switches between internal monologue and third person narrative and a heavy use of ‘as if’ prose where narrator-author boundaries become very blurred. Some of her stories became more lyrical, more compacted and symbolic, abandoning any semblance of conventional story or plot in favour of a poetic meditation on a theme. All of this can make enormous demands upon the reader. Sometimes, on first reading, it’s even hard to know what is going on. But gradually a densely concentrated image or an idea will emerge – the equivalent of a Joycean ‘epiphany’ – and everything falls into place. Her own collection of Selected Stories are UK National Curriculum recommended reading.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2004

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Literature in English

Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Literature in English Twentieth-century Britain

Twentieth-century Britain Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. It was written by the same author as the guidance notes on this page that you are reading right now.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. It was written by the same author as the guidance notes on this page that you are reading right now.