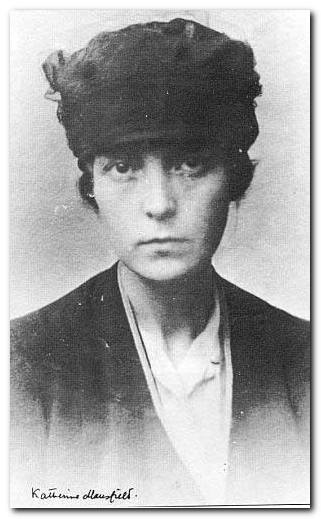

annotated bibliography of criticism and comment

Katherine Mansfield criticism is a bibliography of critical comment on Mansfield and her works, with details of each publication and a brief description of its contents. The details include active web links to Amazon where you can buy the books, often in a variety of formats – new, used, and as Kindle eBooks and print-on-demand reissues. The listings are arranged in alphabetical order of author.

The list includes new books and older publications which may now be considered rare. It also includes versions of older texts which are much cheaper than the original. Others (including some new books) are often sold off at rock bottom prices. Whilst compiling these listings a paperback copy of Antony Alper’s biography The Life of Katherine Mansfield was available at Amazon for one penny.

The Life of Katherine Mansfield – Antony Alpers, Oxford University Press, 1987. This is one of the first serious biographies, written by fellow New Zealander and Mansfield scholar Antony Alpers.

Katherine Mansfield – Ida Constance Baker, London: Michael Joseph, 1971. A memoir by Mansfield’s long-suffering yet most devoted friend.

Katherine Mansfield (Writers & Their Work) – Andrew Bennet, Northcote House Publishers, 2002. This book offers a new introduction to Katherine Mansfield’s short stories informed by recent biographical, critical and editorial work on her life and on her stories, letters and notebooks.

Katherine Mansfield: The Woman and the Writer – Gillian Boddy, Penguin Books, 1988.

Illness, Gender, and Writing: The Case of Katherine Mansfield – Mary Burgan, Johns Hopkins Press, 1994. This study shows how Mansfield negotiated her illnesses in a way that sheds new light on the study of women’screativity. It concludes that Mansfield’s drive toward self-integration was her strategy for writing–and for staying alive.

Radical Mansfield: Double Discourse in Katherine Mansfield’s Short Stories – Pamela Dunbar, Palgrave Schol Print, 1997. A new evaluation of Katherine Mansfield reveals her as an original and highly subversive writer preoccupied with issues like sexuality and the irrationality of the human mind.

Katherine Mansfield – Joanna FitzPatrick, La Drome Press, 2014.

Katherine Mansfield (Key Women Writers) – Kate Fullbrook, Prentice Hall, 1986.

Katherine Mansfield and Her Confessional Stories – Cherry A. Hankin, London: P{algrave Macmillan, 1983.

Katherine Mansfield and Literary Influence – Melinda Harvey, Edinburgh University Press, 2015. This study shows that ‘influence’ is as often unconscious as it is conscious, and can be evidenced by such things as satire, plagiarism, yearning and resentment.

Katherine Mansfield: The Story-Teller – Kathleen Jones, Edinburgh University Press, 2010. Weaving together intimate details from Katherine Mansfield’s letters and journals with the writings of her friends and acquaintances, this study creates a captivating drama of this fragile yet feisty author: her life, loves and passion for writing.

Katherine Mansfield and the Origins of Modernist Fiction – Sydney Janet Kaplan, Cornell University Press, 1991.

Celebrating Katherine Mansfield: A Centenary Volume of Essays – Gerri Kimber (ed), London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. A collection which ncludes essays by major scholars in several areas including musicology, postcolonial theory, epistolary and biographical studies, representing recent developments in Modernist studies and thus exploring her continued literary legacy to contemporary writers.

Katherine Mansfield and World War One – Gerri Kimber (ed), Edinburgh University Press, 2014.The articles in this volume provide us with a greater appreciation of Mansfield in her socio-historical context. In offering new readings of Mansfield’s explicit and implicit war stories, these essays refine and extend our knowledge of particular stories and their genealogy.

Katherine Mansfield and the Art of the Short Story – Gerri Kimber, Palgrave Pivot, 2014. This volume offers an introductory overview to the short stories of Katherine Mansfield, discussing a wide range of her most famous stories from different viewpoints. The book elaborates on Mansfield’s themes and techniques, thereby guiding the reader – via close textual analysis – to an understanding of the author’s modernist techniques.

Katherine Mansfield and Continental Europe: Connections and Influences – Gerri Kimber (ed), London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. This collection of essays offers new interpretations of Katherine Mansfield’s work by bringing together recent biographical and critical-theoretical approaches to her life and art in the context of Continental Europe.

Katherine Mansfield and the Modernist Marketplace: At the Mercy of the Public – Jenny McDonnell, London: Palgrave Schol Print, 2010. This study provides the first comprehensive study of Mansfield’s career as a professional writer in a commercial literary world, during the years that saw the emergence and consolidation of literary modernism in Britain.

Katherine Mansfield: A Darker View – Jeffrey Meyers, Cooper Square Publishers, 2002. This study chronicles her tempestuous relationships (that mixed abuse with devotion) and the years she fought a losing battle with tuberculosis.

Katherine Mansfield’s Fiction – Patrick D. Morrow, Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1993. This book attempts to analyze a major part of Mansfield’s fiction, concentrating on an analysis of the various textures, themes, and issues, plus the point of view virtuosity that she accomplished in her short lifetime.

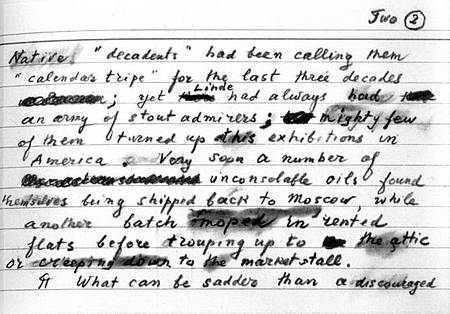

The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks – Margaret Scott, University of Minnesota Press, 2002. The first unexpurgated edition of her private writings. Fully and accurately transcribed, these diary entries, drafts of letters, introspective notes jotted on scraps of paper, unfinished stories, half-plotted novels, poems, recipes, and shopping lists offer a complete and compelling portrait of a complex woman.

Katherine Mansfield: A Literary Life (Literary Lives) – Angela Smith, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000. This study explores Mansfield’s idiosyncratic aesthetic by focusing on her position as an outsider in Britain: a New-Zealander, a woman writer, a Fuavist, and eventually a consumptive.

Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life – Claire Tomalin, London: Penguin, 2012. A biography which captures the creative zest of a writer who was sexually ambiguous, craving love yet quarrelsome and capricious, her beauty and recklessness inspiring admiration, jealousy, rage and devotion.

Katherine Mansfield and Literary Modernism – Janet Wilson (ed), London: Bloomsbury, 2014. Reinterpretations and readings enhanced by new transcriptions of manuscripts and access to Mansfield’s diaries and letters. These essays combine biographical approaches with critical-theoretical ones and focus not only on philosophy and fiction, but class, gender, and biography/autobiography.

© Roy Johnson 2015

More on Katherine Mansfield

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on short stories

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first.

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first. Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Sons and Lovers

Sons and Lovers Women in Love

Women in Love

Leonard Sidney Woolf was born in London in 1880, the third of ten children of Solomon Rees Sydney and Marie (de Jongh) Woolf. When his father died in 1892, Woolf was sent to board at the Arlington House School, a preparatory school near Brighton. From 1894 to 1899 he studied on a scholarship as a day student at St. Paul’s, a London public school noted for its classical studies. In 1899 he won a classical scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge.

Leonard Sidney Woolf was born in London in 1880, the third of ten children of Solomon Rees Sydney and Marie (de Jongh) Woolf. When his father died in 1892, Woolf was sent to board at the Arlington House School, a preparatory school near Brighton. From 1894 to 1899 he studied on a scholarship as a day student at St. Paul’s, a London public school noted for its classical studies. In 1899 he won a classical scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge.

But none of these artists were working class, and before long Party apparatchiks were calling for the suppression of their work and demanding art that followed the Party line. Since the party had a monopoly of the means of production and even the supply of paper, they got what they called for. The result was worthless propaganda of the ‘boy meets tractor’ variety.

But none of these artists were working class, and before long Party apparatchiks were calling for the suppression of their work and demanding art that followed the Party line. Since the party had a monopoly of the means of production and even the supply of paper, they got what they called for. The result was worthless propaganda of the ‘boy meets tractor’ variety.

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp, pretending that Charlotte is ill and in a hospital. He takes Lolita to a hotel, where he meets a strange man (later revealed to be Clare Quilty), who seems to know who he is. Humbert attempts to use sleeping pills on Lolita so that he may molest her without her knowledge, but they have little effect on her. Instead, she consciously seduces Humbert the next morning. He discovers that he is not her first lover, as she had sex with a boy at summer camp. Humbert reveals to Lolita that Charlotte is actually dead; Lolita has no choice but to accept her stepfather into her life on his terms.

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp, pretending that Charlotte is ill and in a hospital. He takes Lolita to a hotel, where he meets a strange man (later revealed to be Clare Quilty), who seems to know who he is. Humbert attempts to use sleeping pills on Lolita so that he may molest her without her knowledge, but they have little effect on her. Instead, she consciously seduces Humbert the next morning. He discovers that he is not her first lover, as she had sex with a boy at summer camp. Humbert reveals to Lolita that Charlotte is actually dead; Lolita has no choice but to accept her stepfather into her life on his terms. One day in 1952, Humbert receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is married, pregnant, and in desperate need of money. Humbert goes to see Lolita, giving her money and hoping to kill the man who abducted her. She reveals the truth: Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte’s and the writer of the school play, checked her out of the hospital and attempted to make her star in one of his pornographic films; when she refused, he threw her out.

One day in 1952, Humbert receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is married, pregnant, and in desperate need of money. Humbert goes to see Lolita, giving her money and hoping to kill the man who abducted her. She reveals the truth: Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte’s and the writer of the school play, checked her out of the hospital and attempted to make her star in one of his pornographic films; when she refused, he threw her out.