tutorial, instructions, and a sample research brief

What is a research proposal?

At post-graduate level of education (after a first degree) it is quite common for research tasks to be part of the curriculum. Don’t worry – you are not expected to unearth some hitherto unknown secret of the universe. The research skills you will learn are simply part of the intellectual equipment required by your subject of study.

The research itself may be preceded by the exercise of writing a proposal for the task you are going to undertake. This research proposal is rather like an extended written preparation for the work you are going to do. Its purpose is to show that you can construct a coherent plan which demonstrates that you are aware of what is required.

Your tutor or supervisor will see from your research proposal that you have prepared efficiently for a long piece of work, and that you are conscious of the disciplines required by your subject. It is also important that what you are proposing is capable of being successfully completed in the time and the circumstances at your disposal.

Here are the steps that should be followed in producing a good, sound research proposal – though some of the smaller details will vary according to the subject being studied.

1. Study the research brief

A research brief is the written instructions for the task you have been asked to complete or a description of the project you have been invited to propose. The number of words will be specified. The issues which you are required to discuss or include will be outlined, and any limitations on the scope of the exercise might be flagged up.

Copy out this research brief and its instructions completely in your preparatory notes. Write out the instruction accurately and in detail to show that you have read all the requirements – some of which it might be easy to miss in a casual reading.

The research brief and instructions will not be included in your final research proposal, but they are an integral part of the materials required to produce it.

2. Identify the formal structure of the proposal

You should demonstrate a clear understanding of the structure required in your research proposal. This might be specified by the department in which you are studying, it might be a matter of tradition in your subject, or you might need to create your own structure.

Look at examples of previous proposals that have been successful. Make a note of the principal headings and sub-headings that have been used. Your own headings should be based on and should refer to everything that has been asked for. Construct the outline headings to start planning your proposal.

3. Choose suitable topic(s) for research

Choose a research topic in which you are genuinely interested, otherwise the project work might become tedious. Make sure the topic of the proposal is something that you can actually accomplish. Do not be over-ambitious. The purpose of the research is a check that you can identify an issue or a hypothesis, then test its validity. You are not being asked to be innovative at this level.

Think ahead to the practical problems you might face in gathering your data. Choose a topic that can be modified slightly in case problems arise.

4. Follow academic conventions

Make sure you know the academic conventions of presentation for the subject. Some popular style guides include the Harvard, the Chicago, the PMLA, and the MHRA conventions.

These style guides on academic referencing and citation are designed to show that you can make accurate and consistent use of other people’s work in your own writing. They will also help you to avoid any suggestion of plagiarism.

Follow the conventions required by the system down to the smallest detail. It is easy to lose marks for not following the conventions, because mistakes are easy for tutors and examiners to spot.

5. Organise your materials

Create a separate folder for each part of your written materials and your data. This applies to both paper and digital files. Keep clearly labelled storage systems for your written arguments, data, bibliography, questionnaires, tables, and data analysis. Don’t keep everything in one long document or one folder.

Long pieces of written work deserve to be handled with respect and good organisation. You will also be able to find your work and control it if it’s well organised.

6. Use cloud storage

Create an account with iCloud or Dropbox or Microsoft Drive and store your materials in the cloud. This will reproduce the system of separate folders that exist on your own computer. Dropbox (and the others) will synchronise the work on your computer with copies stored in the cloud, keeping both up to date as you work on them. The copies are stored safely on remote servers. They can be accessed from any computer – including mobile devices. This means you can access your up-to-date documents wherever you happen to be. This system also keeps your materials safe in the event of computer breakdowns.

Copies stored in the cloud are normally password-protected and available only to the account owner (you). However, it is also possible to have shared folders, so if you happen to be working on a joint project, access can be granted to co-workers.

7. Design an outline plan

Use your list of headings (3) to create an outline plan of the research proposal. The proposal does not need to have any substantial content yet, but the outline is a reminder of all the topics you should keep in mind. The order of the items in the plan can be changed later if necessary. You can also work on the generation of your written proposal in any order you wish. It does not have to be composed in the same order as the research will be conducted.

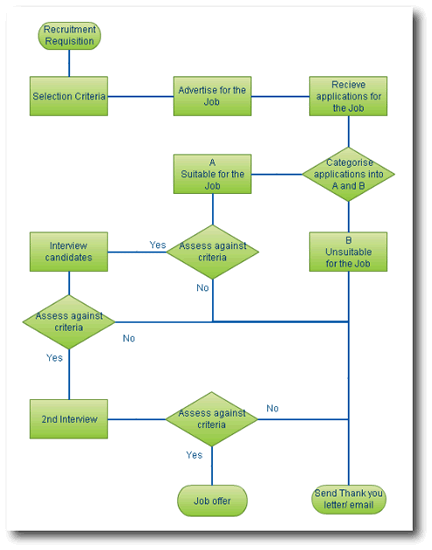

You might find it useful to translate your proposal into some sort of visual flow chart or diagram of events. This will help you to conceptualise the work you are proposing, and it can make clear your intentions for the people who will be assessing your proposal.

a workflow diagram

8. List background reading

At all times, keep a full bibliographic record of any materials you consult whilst designing your proposal. The bibliography will include text books, articles, journals, web sites, and other sources from which you have quoted or which you have consulted during the composition of your proposal. You should include page numbers for easier retrieval and checking of quotations at a later date. Follow the conventions of bibliographic presentation specified by the style guide you are using (4).

9. Acknowledge the ethics of research

Many types of research now require a formal recognition of the ethical issues which might be involved. This applies to such things as conducting surveys amongst the public; using other people’s data; asking people to complete questionnaires; observing people’s behaviour; or taking samples of public attitudes on controversial topics.

You need to show that you are aware of the possible ethical implications of your research and its methodology. You will also need to indicate what practical steps you intend to take.

Examples of any questionnaires or surveys should be included in your final research proposal submission. A successful proposal might also include a contract of agreement or consent to be used with participants.

10. Make a timetable

Work backwards from the submission deadline. Make a calendar that shows the exact number of days available to you. Allocate time in proportion to the task, and make sure you include all stages of composition – from data gathering and background reading, to writing, editing, and checking the finished proposal.

Sample research proposal brief

Extended research proposal and rationale

Submission date: May 9th, 2014.

Word limit: 4,000 words

Decide on a research question related to Linguistics, Applied Linguistics or Language Teaching, which you would like to explore in your MA dissertation. Bear in mind that the research project needs to be small-scale and realistic to complete within the 3-month dissertation period.

Devise research questions/hypotheses and a research methodology that will allow you to gather data needed to answer your research question/test your hypotheses.

Design and produce appropriate research instruments and data collection procedures.

Write up the research proposal as a short paper with an emphasis on:

- justification/motivation for your choice of research area

- research context: understanding of work in the area

- explanation of the research questions/hypotheses

- justification for the methodology used

- reliability and validity issues

- research ethics

- timescale for the research

- awareness of possible limitations of the research

You should make reference to research methodology literature in order to justify your choices throughout the paper. The paper will serve as the basis for a research proposal for the MA dissertation to be undertaken in Semester 3.

Please include a copy of your research instruments in an appendix to your proposal.

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

Doing Your Research Project: A Guide for First-Time Researchers in Education and Social Science is a best-selling UK guide which covers planning and record-keeping, interviewing, reviewing ‘the literature’, questionnaires, and writing the final report. Even if you are studying a subject other than education or social science, this is a wonderfully helpful guide on organising your ideas and your writing at research level. It’s a model of clarity and good sense. Now in its third edition – and deservedly so. Highly recommended.

Doing Your Research Project: A Guide for First-Time Researchers in Education and Social Science is a best-selling UK guide which covers planning and record-keeping, interviewing, reviewing ‘the literature’, questionnaires, and writing the final report. Even if you are studying a subject other than education or social science, this is a wonderfully helpful guide on organising your ideas and your writing at research level. It’s a model of clarity and good sense. Now in its third edition – and deservedly so. Highly recommended. Writing your Doctoral Dissertation: Invisible Rules for Success is a US guide to writing at post-graduate level which uses practical examples, is strong on planning, and offers advice on negotiating the process of research – from making an application to submitting a dissertation. It’s also good on the issue of selecting a research topic and developing it into a feasible project. One of the features which has made this a popular choice is that it offers tips from former students on the problems they have faced in doing research – and how they have overcome them.

Writing your Doctoral Dissertation: Invisible Rules for Success is a US guide to writing at post-graduate level which uses practical examples, is strong on planning, and offers advice on negotiating the process of research – from making an application to submitting a dissertation. It’s also good on the issue of selecting a research topic and developing it into a feasible project. One of the features which has made this a popular choice is that it offers tips from former students on the problems they have faced in doing research – and how they have overcome them. If you have any serious intention of preparing text for publication, then Copy-Editing: The Cambridge Handbook for Editors, Authors and Publishers is your encyclopedia on typography, style, and presentation. It has become the classic UK guide and major source of reference for all aspects of editing and text-presentation, covering every possible bibliographic detail. It also covers a wide range of subjects – from languages to mathematics and music – as well as offering tips on copyright and preparing text for electronic publication.

If you have any serious intention of preparing text for publication, then Copy-Editing: The Cambridge Handbook for Editors, Authors and Publishers is your encyclopedia on typography, style, and presentation. It has become the classic UK guide and major source of reference for all aspects of editing and text-presentation, covering every possible bibliographic detail. It also covers a wide range of subjects – from languages to mathematics and music – as well as offering tips on copyright and preparing text for electronic publication. The Classic Guide to Better Writing is more-or-less what its title suggests. It’s a best-selling US guide with emphasis on how to generate, plan, and structure your ideas. It also covers basic grammar, good style, and common mistakes. The approach is step-by-step explanations on each topic, plenty of good advice on how to avoid common mistakes, and tips on how to gain a reader’s attention. Suitable for all types of writing, it well deserves its good reputation.

The Classic Guide to Better Writing is more-or-less what its title suggests. It’s a best-selling US guide with emphasis on how to generate, plan, and structure your ideas. It also covers basic grammar, good style, and common mistakes. The approach is step-by-step explanations on each topic, plenty of good advice on how to avoid common mistakes, and tips on how to gain a reader’s attention. Suitable for all types of writing, it well deserves its good reputation. If you need just one book which will answer all your questions on writing – from punctuation to publication – then this is it. The Little, Brown Handbook is an encyclopaedic US guide to all aspects of writing. It includes vocabulary, punctuation, grammar, style, document design, MLA conventions, editing, bibliography, and the Internet. All topics are profusely illustrated and cross-indexed, and some of the longer entries are virtually short essays. It also has self-assessment exercises so that you can check that you have understood the contents of each chapter. The Swiss army penknife of writing guides. Highly recommended.

If you need just one book which will answer all your questions on writing – from punctuation to publication – then this is it. The Little, Brown Handbook is an encyclopaedic US guide to all aspects of writing. It includes vocabulary, punctuation, grammar, style, document design, MLA conventions, editing, bibliography, and the Internet. All topics are profusely illustrated and cross-indexed, and some of the longer entries are virtually short essays. It also has self-assessment exercises so that you can check that you have understood the contents of each chapter. The Swiss army penknife of writing guides. Highly recommended. Hart’s Rules for Compositors and Readers at the University Press Oxford This is a UK classic guide to the finer points of editing and print preparation, spelling and typography. It was first written as the style guide for OUP, but quickly established a reputation well beyond. There’s no hand-holding here. Everything is pared to the bone. the centre of the book deals with ‘difficult’ and irregular spellings. A masterpiece of compression, it is now in its thirty-ninth edition. This is one for professionals rather than student writers.

Hart’s Rules for Compositors and Readers at the University Press Oxford This is a UK classic guide to the finer points of editing and print preparation, spelling and typography. It was first written as the style guide for OUP, but quickly established a reputation well beyond. There’s no hand-holding here. Everything is pared to the bone. the centre of the book deals with ‘difficult’ and irregular spellings. A masterpiece of compression, it is now in its thirty-ninth edition. This is one for professionals rather than student writers. The Oxford Dictionary for Writers & Editors . This is a specialist dictionary for writers, journalists, and text-editors. Unlike most dictionaries, it does not offer explanations of the words meanings. It deals with problematic English and foreign words, offering correct spellings and consistent usage in the OUP house style. By concentrating on difficult cases, it saves you a lot of time. The latest edition also includes American spellings. Strongly recommended.

The Oxford Dictionary for Writers & Editors . This is a specialist dictionary for writers, journalists, and text-editors. Unlike most dictionaries, it does not offer explanations of the words meanings. It deals with problematic English and foreign words, offering correct spellings and consistent usage in the OUP house style. By concentrating on difficult cases, it saves you a lot of time. The latest edition also includes American spellings. Strongly recommended. The Elements of Style. This is an old favourite – a ‘bare bones’ guidance manual which cuts out everything except the essential answers to the most common writing problems. It covers the elements of good usage, how to write clearly, commonly misued words and expressions, and advice on good style. The emergency first-aid kit of writing guides. It’s very popular, not least because it’s amazingly cheap. Suitable for beginners. There’s an online version available if you do a search – but the cost of a printed version will pay dividends.

The Elements of Style. This is an old favourite – a ‘bare bones’ guidance manual which cuts out everything except the essential answers to the most common writing problems. It covers the elements of good usage, how to write clearly, commonly misued words and expressions, and advice on good style. The emergency first-aid kit of writing guides. It’s very popular, not least because it’s amazingly cheap. Suitable for beginners. There’s an online version available if you do a search – but the cost of a printed version will pay dividends. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. This is a modern American classic guidance manual for academic writing. It covers everything from abbreviations and numbers to referencing and page layout. It also includes sections showing how to lay out tables and statistics; lots on bibliographic referencing; and how to deal with public and government documents. The latest edition also includes advice on word-processing.

A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. This is a modern American classic guidance manual for academic writing. It covers everything from abbreviations and numbers to referencing and page layout. It also includes sections showing how to lay out tables and statistics; lots on bibliographic referencing; and how to deal with public and government documents. The latest edition also includes advice on word-processing. Style: Ten Lessons in Clarity and Grace. This is a popular guide – particularly amongst creative writing enthusiasts. It offers advice for improving your writing – by putting its emphasis on editing for clarity, creating structure, and keeping the audience in mind. These lessons are useful for all types of writing however. It has plenty of illustrative examples and exercises, an appendix with advice on punctuation, and a good glossary. Recommended.

Style: Ten Lessons in Clarity and Grace. This is a popular guide – particularly amongst creative writing enthusiasts. It offers advice for improving your writing – by putting its emphasis on editing for clarity, creating structure, and keeping the audience in mind. These lessons are useful for all types of writing however. It has plenty of illustrative examples and exercises, an appendix with advice on punctuation, and a good glossary. Recommended. Successful Writing for Qualitative Researchers. This is one for specialist academic writing at post-graduate level. It covers all the stages of creating a scholarly piece of work – from the preparation of a project through to the completion and possible publication of the finished article. Includes sections on style, editing, and collaborative writing. It takes a positive and encouraging tone – which will be welcome to those embarking on such tasks for the first time.

Successful Writing for Qualitative Researchers. This is one for specialist academic writing at post-graduate level. It covers all the stages of creating a scholarly piece of work – from the preparation of a project through to the completion and possible publication of the finished article. Includes sections on style, editing, and collaborative writing. It takes a positive and encouraging tone – which will be welcome to those embarking on such tasks for the first time. On Writing Well. This is a best-selling title, now in its sixth edition. It offers reassuring guidance from an experienced journalist on writing more effectively in a number of genres. He covers interviews, travel writing, memoirs, sport, humour, science and technology, and business writing. The approach is to take a passage and analyse it, showing how and why it works, or where it might be improved. It is particularly good on editing and re-writing.

On Writing Well. This is a best-selling title, now in its sixth edition. It offers reassuring guidance from an experienced journalist on writing more effectively in a number of genres. He covers interviews, travel writing, memoirs, sport, humour, science and technology, and business writing. The approach is to take a passage and analyse it, showing how and why it works, or where it might be improved. It is particularly good on editing and re-writing.