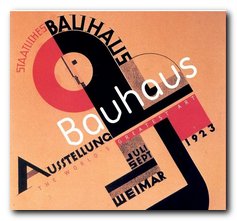

design, modernism, and constructivism

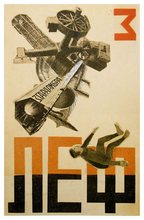

Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956) was one of the most influential artists to emerge from the explosion of Russian modernism which took place between 1915 and 1923. Initially working as a painter, he stripped bare the canvas and worked with ruler and compasses to devise minimalist pictures which he described as ‘subjectless’. But then given the opportunities presented by the early years of the revolution, he went on to become a designer in furniture and fabrics, ceramics, posters, typography, stage and film design, exhibition display, and radical innovations in photography. He was a central figure in the movement of Russian constructivism, a radical activist, a theorist, teacher, and a pioneer of photo-montage. Alexander Rodchenko Design is an elegantly illustrated introduction to the full range of his work.

After the early abstract designs he moved on to public artworks – kiosks, posters, and theatre designs which you could say provided him with a subject – yet he continued to create what he called ‘spatial compositions’, many of which look like bicycle wheels distorted into three dimensional sculptural arrangements.

After the early abstract designs he moved on to public artworks – kiosks, posters, and theatre designs which you could say provided him with a subject – yet he continued to create what he called ‘spatial compositions’, many of which look like bicycle wheels distorted into three dimensional sculptural arrangements.

He worked alongside and sometimes in collaboration with Malevich, Kandinsky, and Tatlin, developing his abstract work into three-dimensional paintings, product designs, and constructions that were half way between art works and domestic objects. It was in the spirit of the new communism to produce an art that aimed to be useful, classless, and practical. This was the aim of what came to be called ‘Constructivism’, even if its results were what we would now call modernist art.

In the early 1920s he produced the work for which he is best known – the combinations of collage images, new typography, and asymmetric graphic design which created the hallmark of Russian modernism. It is this brief period of state-sponsored radical designs that still have an influence today – as you can see in the work of Neville Brody and his many imitators.

His work in the late 1920s and 1930s centred largely on photography, much of it featuring objects shot from unusual angles – street scenes from overhead, trees and chimneys from ground level, all objects highlighted wherever possible by dark expressive shadows.

The illustrations are very well chosen to avoid some of the better-known images. Instead, they draw on quite rare materials from the Rodchenko and Stepanova archive in Moscow, the Burman Collection in New York, and the David King collection in London.

It’s amazing that such an original and gifted artist survived the Stalinist purges (unlike so many others) but then he did produce propaganda work which glorified the regime – including even such projects as the construction of the White Sea Canal in 1933 which cost the lives of 100,000 GULAG prisoners.

In fact the depictions of his subjects become more and more heroic, almost in inverse proportion to the degree of social and political misery in the Soviet Union under Stalin. There is very little evidence (anywhere) of his work beyond 1940, even though he lived until 1956 – although there is one astonishing image in this collection dated 1943-44 which you would swear was a Jackson Pollock painting. But it seems quite obvious that the creative highpoint of his career is the 1920s, when he was free to experiment and theorise with his fellow pioneers, and even (dare one say it) when the state encouraged and supported such experimentation.

In fact the depictions of his subjects become more and more heroic, almost in inverse proportion to the degree of social and political misery in the Soviet Union under Stalin. There is very little evidence (anywhere) of his work beyond 1940, even though he lived until 1956 – although there is one astonishing image in this collection dated 1943-44 which you would swear was a Jackson Pollock painting. But it seems quite obvious that the creative highpoint of his career is the 1920s, when he was free to experiment and theorise with his fellow pioneers, and even (dare one say it) when the state encouraged and supported such experimentation.

The series of design monographs of which this volume is part feature very high design and production values. They are slim but beautifully stylish productions, each with an introductory essay, and all the illustrative material is fully referenced. Even the cover design is taken from Rochenko’s work. It’s from a 1923 poster advertising Zebra biscuits.

© Roy Johnson 2010

John Milner, Rodchenko: Design, Suffolk: Antique Collectors Club, 2009, pp.98, ISBN: 1851495916

More on art

More on media

More on design

Strangely enough, there was no Art Nouveau school of painting, mainly because it constituted an approach to design. It was in the realm of posters, woodcuts, illustrated books, and typography that it made its greatest impact, and there are excellent examples of posters by Lautrec, Mucha, and Bonnard. These were works which gave birth to the figure that came to symbolise fin de siecle Paris and la Belle Epoque – a young woman with serpentine hair, clad fashionably in jewelled or feathered headgear and wearing immense sweeping skirts, all of which flowed abundantly to fill the frame of the picture. It’s amazing to realise that these romantically stylised images were being used to advertise such mundane objects as bicycles, wine, household soap, and cigarette papers.

Strangely enough, there was no Art Nouveau school of painting, mainly because it constituted an approach to design. It was in the realm of posters, woodcuts, illustrated books, and typography that it made its greatest impact, and there are excellent examples of posters by Lautrec, Mucha, and Bonnard. These were works which gave birth to the figure that came to symbolise fin de siecle Paris and la Belle Epoque – a young woman with serpentine hair, clad fashionably in jewelled or feathered headgear and wearing immense sweeping skirts, all of which flowed abundantly to fill the frame of the picture. It’s amazing to realise that these romantically stylised images were being used to advertise such mundane objects as bicycles, wine, household soap, and cigarette papers.

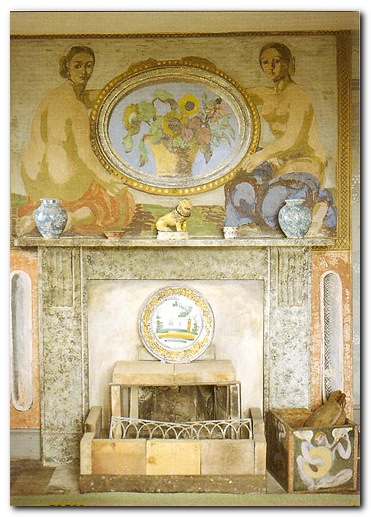

It is most famous for the fact that Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant covered the entire surface of the house – walls, fireplace, cupboards, tables, chairs – with their decorations and paintings, an impulse that was also part of the

It is most famous for the fact that Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant covered the entire surface of the house – walls, fireplace, cupboards, tables, chairs – with their decorations and paintings, an impulse that was also part of the

He was just too young to make a major contribution to the Festival of Britain in 1951, but well-enough connected with its major graphic designers to help him launch a successful career.

He was just too young to make a major contribution to the Festival of Britain in 1951, but well-enough connected with its major graphic designers to help him launch a successful career. There’s an overall feeling of softness and a deep feeling for English traditions. But this isn’t to say that his work is feeble or nostalgic. Indeed, some of his most striking graphics are the posters designed to support radical social causes, such as his opposition to the war in Iraq.

There’s an overall feeling of softness and a deep feeling for English traditions. But this isn’t to say that his work is feeble or nostalgic. Indeed, some of his most striking graphics are the posters designed to support radical social causes, such as his opposition to the war in Iraq.