conflict, culture, language, and literature 1914-1918

Literature and the Great War is a study of the relationship between language, literature, and the events of the conflicts that took place between 1914 and 1918. It also addresses the fact that quite a lot of what we call ‘war poetry’ and ‘first world war memoirs’ was not produced during that period, but many years later – for very good reasons.

With the exception of poetry, which can quickly capture impressions and emotions on the fly, most writing about major events in other genres such as stories, novels, documentaries, histories, and autobiographies require a period of reflection and digestion before they can be properly expressed. This is especially true of events as cataclysmically disruptive as the first world war – which turned the whole world’s view of itself upside down.

There were memorable and enduring works written during the conflict — Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire (1916) and the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Edward Thomas. However, the majority of works which seem to encapsulate both the horrors of the war and the almost universal sense of disillusionment which followed were produced almost a decade later — Robert Graves Goodbye to All That (1929), Ernest Hemingway A Farewell to Arms (1929), Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero (1929), Siegfried Sassoon Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), R.C. Sheriff Journey’s End (1929), Erich Maria Remarque All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

There were memorable and enduring works written during the conflict — Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire (1916) and the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Edward Thomas. However, the majority of works which seem to encapsulate both the horrors of the war and the almost universal sense of disillusionment which followed were produced almost a decade later — Robert Graves Goodbye to All That (1929), Ernest Hemingway A Farewell to Arms (1929), Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero (1929), Siegfried Sassoon Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), R.C. Sheriff Journey’s End (1929), Erich Maria Remarque All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

There are a number of explanations for this delay. Many people felt that the horrors of the war were almost too shocking to write about at the time – especially when official propaganda and the newspapers were telling everybody about ‘heroic’ victories and not mentioning the vast number of men slaughtered (the hundreds of thousands killed were described as ‘wastage’).

After the war very few combatants wanted to talk about their experiences, and those who had survived understandably wanted to simply get back to normal life, often feeling guilty about those they had left behind on the Somme, Passchendale, and Gallipoli.

Because everyone had been persuaded that it had been a ‘war to end all wars’ there was a general sense that optimism would prevail. But then in the 1920s came a period of economic collapse, austerity, and poverty throughout most of Europe. Instead of having fought a war to achieve a better world, it appeared that nothing had been achieved at all, and the huge sacrifice of lost lives had been wasted. .It was the period from late 1920s onward when the spate of angry, critical, and anti-establishment narratives concerning 1914—1918 were produced

Nor should it be thought that during the war itself the public were eager for critical accounts of the carnage, the gassings, and the colossal numbers of people killed. Some of the most popular publications at the time were patriotic and religious works speaking to ‘heroism’, ‘sacrifice’. and ‘victory’.

Stevenson’s (persuasive) argument is that society in the post-war period felt saturated by this sort of language, and writers purged their vocabularies of these now-corrupted abstract generalisations. They used instead a language of concrete nouns, in which only that-which-can-be-known was named. Hence the rise in popularity in the 1920s of writers such as Ernest Hemingway, whose terse and pared-down literary prose style had been shaped by his experience of the first world war:

I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice and the expression in vain … I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago …. Abstract words such as glory, honour, courage or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.

The Sun Also Rises (1926) and A Farewell to Arms (1929) were enormously popular at the time, and went on to influence two or three generations of writers (particularly writers of thrillers and crime fiction) until the fashion for this sort of writing faded (following Hemingway’s suicide) in the 1960s.

Stevenson argues that the war produced a fracturing of time and language. Events began to be described as ‘pre-war’ and post-war’; double summer-time was introduced; and ordinary men and women were plunged into a linguistic vortex in which official language in no way reflected the reality they faced every day in the trenches.

An interesting point he makes about the language of the war is that many of the volunteers and conscripts who took part from the early days of 1914 onwards would be young men (almost boys) who at that time had probably never travelled more than a few miles beyond their own towns and villages. Consequently, since there was at that time, no national broadcasting system, they would never have heard speech other than their own regional accents.

In addition to this, they were plunged into Picardy, where the vast majority of them had never heard the French language spoken before. It is not surprising that towns such as Ypres and Auchonvillers were translated into ‘Wipers and ‘Ocean Villas’ and indeed the satirical newspaper produced by the troops was called the Wipers Times. Newly conscipted men also had to grapple with enormous amounts of army slang and jargon – some of it remnants of the imperial past. Words such as cushy, blighty, and dekko were Hindi or Urdu in origin.

The latter part of the book is devoted largely to the reception and evaluation of poetry produced during the war and in the years since, reminding us that at the time religious and patriotic poetry was far more highly regarded, whereas the critical reputation of writers such as Owen, Thomas, and Sassoon has taken much longer to establish

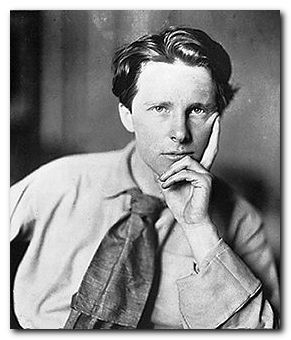

I was glad to see that he put the reputation of Rupert Brooke into perspective. Brooke had glorified a jingoistic sense of Englishness and war prior to 1914 but didn’t actually have any first-hand experience of combat – dying of a rather inglorious flea bite before he reached Gallipoli.

Stevenson does his best to be fair to modernists such as T.S.Eliot and Virginia Woolf, but he misses the opportunity to note that almost the whole of the Bloomsbury Group and its adherents were pacifists during 1914-1918. And this was not based simply on an unwillingness to fight, but on a genuine sense of internationalism and the belief that the war was a huge mistake which need not have taken place. Indeed, before the war had even ended Leonard Woolf helped set up the League of Nations (which went on to become the United Nations) with the sole aim of preventing any further conflicts of its size and kind between nations.

This was an extremely unpopular view to hold at the time – though it has become increasingly sane with hindsight. People were jailed for ‘conscientious objection’ and of course this is a period when young men were executed and crucified in no-man’s-land for crimes of ‘cowardice’ and falling asleep on duty. The only other people to oppose the war on internationalist grounds were figures such as Trotsky and Lenin.

Stevenson’s final chapter considers revisionist histories of the war which have been produced in recent years. He gives their defence of the blundering generals and the gigantic carnage a fair hearing, but eventually undermines their arguments with a few well chosen quotations that emphasise his concluding argument – that we need to read closely and not be swayed by rhetoric and false metaphors.

Revisionist history cannot be accused of ignoring the war’s loss and mutilation. [Gary Sheffield’s] Forgotten Victory is regularly attentive to the ‘callous arithmetic of battle’ and the ‘butcher’s bill’ that resulted. Yet Sheffield also suggests that at one stage that the Canadians’ capture of Vimy Ridge in 1917 was achieved ‘with relatively little difficulty, although at the cost of 11,000 casualties’. Such remarks cast doubt on his promise of ‘analysis based on firm grasp of the facts’. Avoidance of difficulty, even relatively, at the cost of 11,000 casualties, is not fact but interpretation, the kind of interpretation the generals were apt to make themselves.

© Roy Johnson 2013

Randall Stevenson, Literature and the Great War 1914-1918, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp.262, ISBN: 019959645X

The second part of the book is the heart of the matter – words grouped into sets according to their vowel sound. These are actually listed in the order of word endings – as in -ar, -ee, and -ng. So the listings for -ar run aargh, Accra, afar, aide mémoire and so on. This might sound complicated, but becomes clearer with use, as in the example which follows here.

The second part of the book is the heart of the matter – words grouped into sets according to their vowel sound. These are actually listed in the order of word endings – as in -ar, -ee, and -ng. So the listings for -ar run aargh, Accra, afar, aide mémoire and so on. This might sound complicated, but becomes clearer with use, as in the example which follows here.

Rupert Brooke (1887—1915) was only ever on the fringe of the Bloomsbury Group – but he was well acquainted with its central figures, such as

Rupert Brooke (1887—1915) was only ever on the fringe of the Bloomsbury Group – but he was well acquainted with its central figures, such as

T.S.Eliot (Thomas Stearns) was born in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1888. His father was a successful businessman, and his mother wrote poems. From 1898 to 1905 he attended Smith Academy where he studied French, German, Latin, and Ancient Greek. At the age of fourteen he began to write poetry, heavily under the influence of The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam which enjoyed a vogue around that time. He published his first poem in the Smith Academy Record when he was fifteen.

T.S.Eliot (Thomas Stearns) was born in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1888. His father was a successful businessman, and his mother wrote poems. From 1898 to 1905 he attended Smith Academy where he studied French, German, Latin, and Ancient Greek. At the age of fourteen he began to write poetry, heavily under the influence of The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam which enjoyed a vogue around that time. He published his first poem in the Smith Academy Record when he was fifteen.