secrecy, intellectual elitism, and cultural history

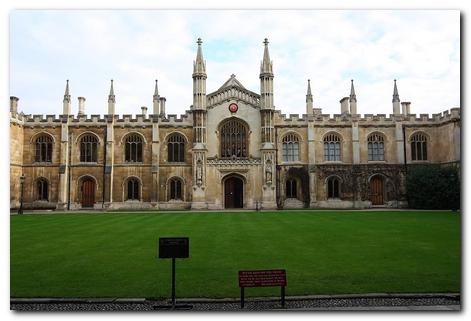

The Cambridge Apostles was a quasi-secret discussion group (also known as The Cambridge Conversazione Society) that was established at Cambridge University in the nineteenth century, drawing its members largely from Christ’s, St John’s, Jesus, Trinity, and King’s Colleges. It was called The Apostles because there were originally twelve founder members, who met on Saturday night to discuss a given topic. Members were generally undergraduates, but post graduates and even teaching staff were permitted. Membership was strictly by invitation only, and former members of the group were called ‘angels’. The group met at midnight, drank coffee, and ate sardines on toast – which were called ‘Whales’.

Cambridge University – King’s College

The Cambridge Apostles – history

The group was founded in 1830 by George Tomlinson, who went on to become the Bishop of Gibraltar – a fact that reflects both the religious and the evangelical origins of the group. Most of its early members were destined to become clergymen of one kind or another. It began as a debating society which met each Saturday night, and the element of secrecy was such that no member even knew he had been proposed until he was elected.

The group had its own coded language. Someone being considered for membership was called an ’embryo’. All matters relating to the group were known as ‘reality’, whilst everything and all people outside it were referred to as ‘phenomena’. All records of membership and copies of delivered talks were kept in a wooden trunk called ‘the ark’.

Although the group was religious in origin and debated issues of conscience and belief, it gradually changed from an ideology of Toryism to a radical examination of general ethics. An early influence was Samuel Taylor Coleridge – not as a poet, but as a social philosopher who was renowned in his day both as a powerful intellectual and a great talker. He was also given to fuelling his tirades by doses of laudanum (opium).

Tennyson was an early member, but was fined five shillings and asked to resign for non-attendance. However, he was later re-admitted as an ‘angel’. The spirit of radicalism was in the group from its earliest days. They debated the possibility of admitting women (motion defeated) and gave assistance to the Spanish revolutionaries of 1850.

The group facilitated the establishment of lifelong friendships and in many cases established an Old Boys network which oiled the wheels of promotion in employment, be it in the university system, the Church, or in government. The close bonding also merged effortlessly into the homosexuality that easily took root in an all male environment in which females were generally regarded as lesser beings:

the theory that the love of a man for man was greater than that of a man for woman became an Apostolic tradition.

This tendency was fuelled intellectually later in the century by the pervasive influence of G.E. Moore who promoted a philosophy of close friendships and the pursuit of both pleasure and ‘the Good’ – without specifying what it was. In the early twentieth century this continued under the influence of Lytton Strachey (‘the arch bugger of Bloomsbury’) who controlled events and set the tone of the Apostles as its secretary and founded a powerful leadership with his fellow homosexual and one time lover, John Maynard Keynes.

The Bloomsbury Group

Without a doubt, the father of the Bloomsbury Group was the Victorian biographer and essayist, Sir Leslie Stephen. He attended Trinity Hall Cambridge and was elected a fellow – though not as an Apostle. However, his two sons Thoby and Adrian were also Cambridge undergraduates, where they became friends with Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Maynard Keynes, Saxon Sydney-Turner, and E.M. Forster, all of whom were Apostles.

These friendship networks were formed in the university, but then consolidated when individuals began to socialise at the soirees held by Thoby Stephen and his sisters, Vanessa (painter) and Virginia (writer) in their new home in Gordon Square, which at that time was considered a slightly bohemian district of London. Vanessa eventually married the apostle Clive Bell (art critic) and Virginia married the writer Leonard Woolf. There was therefore a considerable overlap between the Apostles and the Bloomsbury Group, which eventually included people such as Roger Fry (art critic and painter) and Desmond MacCarthay (journalist and editor) both of whom were Apostles.

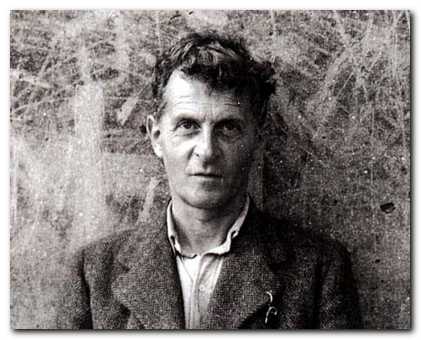

To be elected as an Apostle was generally regarded as a recognition of outstanding ability and talent, but some of the members of this elite group were quite unorthodox. The reclusive Saxon Sydney-Turner for instance, described by Leonard Woolf as ‘an absolute prodigy of learning’, attended meetings but hardly contributed a single word to discussion. When he returned from his holidays he showed photographs of rural Finnish railway stations and was considered a monumental bore. The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein was elected a member in 1912, but resigned almost immediately because he could not tolerate the atmosphere of levity and the style of humour prevalent amongst members.

Desmond MacCarthay on the other hand was a great talker and a writer considered to be of great promise. However, the promise never resulted in the production of the great novel he was always threatening to write. His gifts as a speaker are illustrated by a famous incident from a meeting of the Bloomsbury Memoir Club, at which attendees would give papers recalling past events and fellow members. E.M. Forster recalls:

he had a suit-case open before him. The lid of the case, which he propped up, would be useful to rest his manuscript upon, he told us. On he read, delighting us as usual, with his brilliancy, and humanity, and wisdom, until – owing to a slight wave of his hand – the suit-case unfortunately fell over. Nothing was inside it. There was no paper. He had been improvising.

It is interesting to note the subtle connections that allowed the Apostles to control much of the literary and intellectual life in its heyday in the early twentieth century. Leonard Woolf was in charge of the literary pages of The Nation, Desmond MacCarthy did the same at the New Statesman, and Lytton Strachey’s uncle was at the helm of The Spectator.

During the first world war the society was split between pacifists – Bertrand Russell, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Saxon Sydney-Turner – and those who chose to fight – Ralph Wedgwood and Rupert Brooke – the ‘war poet’ who was never in the war and who died of an infected mosquito bite.

In the post-war period of the 1920s the society took a generally leftward direction and the first of the Marxists formed a sub-group, supporting the miners during the General Strike. The other momentous event in 1929 was the re-election of Ludwig Wittgenstein who was to dominate intellectual life at the university during the next ten years, although he did not get on well with the other influential figure of the 1930s, F.R. Leavis.

The next generation to join the Apostles included figures such as Julian Bell (son of apostle Clive Bell and his wife Vanessa) and the art historian Anthony Blunt. There was a generally sympathetic attitude taken towards the Soviet Union shared by many except those who had actually been there. The central event of this period was the Spanish Civil War when almost everyone supported the Republicans. But the same period also saw the establishment of what later became known as the Cambridge Spy Ring.

During the second world war Cambridge and its Apostles were all active in the fight against Nazism – some of them at Bletchley Park working on the Enigma decoding system under the direction of the brilliant mathematician Alan Turing – who was not elected an Apostle.

In the 1950s and 1960s the society included names which form a link to the modern world: Arnold Kettle, literary critic who became Professor at the Open University; Peter Shore, the Labour Party minister; the historian and unrepentant Marxist, Eric Hobsbawm; and polymath doctor and theatre director, Jonathan Miller. The society eventually decided to include women – though these remain few in number.

The Cambridge Spy Ring

In the 1930s the Apostles were largely sympathetic to left-wing causes and continued to generate personal links on the basis of their homosexual links. Both of these issues were at the root of the spy ring, which was formed between Anothony Blunt, Guy Burgess, Kim Philby, and Donald MacLean. Various other contemporaries have been accused and investigated as spies, but without positive outcomes.

Anthony Blunt is possibly the most spectacular example of establishment deception, since he was a friend of the royal family, eventually became keeper of the Queen’s pictures, and was given a knighthood. But in 1953 the American writer Michael Straight, who was an apostle and publisher of The New Republic was uncovered as a Soviet spy and named Blunt in his confession. Blunt named others in his deposition, and was eventually stripped of his knighthood by Margaret Thatcher in 1979.

In 1951 Burgess and MacLean both fled to Moscow when they came under suspicion of espionage. MacLean became a respected Soviet citizen, but Burgess never even bothered to learn Russian and lived in a seedy flat furnished with English memorabilia, became more or less an alcoholic, and died aged fifty-two.

© Roy Johnson 2016

The Cambridge Apostles – study resources

![]() The Cambridge Apostles – Early Years – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Apostles – Early Years – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Apostles – Early Years – Amazon US

The Cambridge Apostles – Early Years – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Apostles – A History – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Apostles – A History – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Apostles – A History – Amazon US

The Cambridge Apostles – A History – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Apostles – 1820-1914 – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Apostles – 1820-1914 – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Apostles – 1820-1914 – Amazon US

The Cambridge Apostles – 1820-1914 – Amazon US

![]() G.E. Moore and the Cambridge Apostles – Amazon UK

G.E. Moore and the Cambridge Apostles – Amazon UK

![]() G.E. Moore and the Cambridge Apostles – Amazon US

G.E. Moore and the Cambridge Apostles – Amazon US

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature