tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

The Voyage Out was Virginia Woolf’s first full length novel. It was written and re-written many times between (probably) 1907 and its eventual publication by Duckworth in 1915 (the publishing house run by her step-brother Gerald Duckworth). It was originally called Melymbrosia, and an earlier version was completed in 1912. This alternative version was published with that title in 1962. But when her own publishing house the Hogarth Press produced a Uniform Edition of Woolf’s works in 1929, it was the later 1915 version that was used as the definitive text.

first edition 1915

The Voyage Out – critical comment

The principal theme

Virginia Woolf was to devote a great deal of her career as a novelist and essayist to issues of women’s education and their position in society – from her earliest story Phyllis and Rosamond (1906) to her epoch-making attack on patriarchy Three Guineas (1938). Her first novel is no exception – as an exploration of a young woman who has received no formal education and who has been brought up at home in a manner which does not prepare her for any sort of independent adult life.

there was no subject in the world which she knew accurately. Her mind was in the state of an intelligent man’s in the beginning of the reign of Queen Elizabeth; she would believe practically anything she was told. invent reasons for anything she said. The shape of the earth, the history of the world, how trains worked, or money was invested, what laws were in force, which people wanted what, and why they wanted it, the most elementary idea of a system in modern life—none of this had been imparted to her by any of her professors or mistresses

Rachel is intensely conscious of her lack of formal education, her powerlessness in society, and her exclusion from the male-dominated world of governance and decision-making. Her one consolation is that she has been left undisturbed to develop her artistic flair for piano-playing.

The experimental novel

Virginia Woolf is rightly celebrated as one of the most talented innovators of the modernist period for the work she produced between Jacob’s Room in 1922 and The Waves in 1932. For that reason her earlier first novel The Voyage Out (1915) is often classified as ‘traditional’ or ‘conventional’. That is partly because its main subject is a young woman’s ‘coming of age’, partly because the narrative follows a linear chronology, and partly because the book contains a substantial proportion of well-observed middle-class social life which could have come from any number of nineteenth century novels – from Jane Austen to George Meredith.

But the novel is far from conventional – for a number of reasons. First, it does not have a ‘plot’ as such. A group of people go on a cruise from London to Latin America. Whilst there, they organise an expedition into the interior, and when they get back one of them dies of fever. There is no mystery to be solved; there are no surprising coincidences or revelations; the one serious romance between the characters is abruptly terminated by Rachel’s death; and the narrative is even denied any structural closure. There is no return journey to the starting point:.

Instead we are presented with what Rachel Vinrace calls for during the events of the novel – “Why don’t people write about the things they do feel?” . Despite all the symbolism of a first journey away from home, a first love affair, and the dawning of mature consciousness which Rachel experiences, the bulk of the novel is taken up with what people say and think about each other. This was a bold alternative to the plot-driven novels of the late Victorian era.

[In fact Woolf’s next novel, Night and Day (1919) is far more conventional. Another young middle-class woman, Katharine Hilbery, is facing the limited social choices offered to her in life – but the novel is grounded in a family saga and a rather complex love quadrangle.]

Point of view

The other major innovation Woolf developed in this novel is what might be called the floating or roaming point of view. Novelists very often choose to relay their narratives from the point of view of a single character or a narrator who might be a character or a surrogate for the author. Woolf uses a combination of a reasonably objective third person narrative mode with passages in which the point of view switches from one character to another. She does this in order to explore three separate issues which she developed even further in her later novels.

The first of these issues is what might be called the relativity of human perception – how one person perceives another, and how this perception might change from one moment to the next. The second is to explore the distance which separates human beings, even when they feel that they closely understand each other. The third is to explore the differences between what a person does and what is said – or to point directly at internal contradictions in the human psyche. Very often people say things they do not mean, or they make statements about themselves which are contradicted by their behaviour.

Setting

The novel begins in London, then moves via a very convincing storm at sea to Portugal, where the Dalloways join the ship. This part of the narrative is quite credible, and is possibly based on a journey at sea Virginia Woolf made to Portugal with her younger brother Adrian in 1905. But after the Dalloways are dropped off (almost parenthetically) in North Africa the location switches with virtually no transition to the fictitious Santa Marina.

The implication is that this is located somewhere near the mouth of a ‘great river’ – presumably the Amazon. But despite adding historical background details of European colonialism in the region, and a sprinkling of exotic vegetation which Woolf adds to the narrative, the topography of the story never becomes really convincing.

It is significant that one feature of the indigenous vegetation that she mentions repeatedly is cypress trees – ‘at intervals cypresses striped the hill with black bars’ – which are characteristic of the Mediterranean but certainly not of tropical Latin-American vegetation. This might be ignored were it not for the fact that she was to do something very similar in later novels.

The background events of Jacob’s Room (1922) concerning Betty Flanders are supposed to be set in Scarborough, on the East coast of Yorkshire, but these scenes are never as convincing as the others set in Cambridge and London. And nobody in their right mind can read To the Lighthouse (1927) without visualising its setting as St Ives and the Godrevy Lighthouse where Woolf spent many summer holidays in her childhood. Yet the novel is supposed to be set in the Hebrides. This remains completely unconvincing throughout the whole of the novel.

Weaknesses

There are a number of minor characters who are written into the story line of The Voyage Out, but who then disappear from the text as if they have been forgotten. Mrs Chairley the Cockney housekeeper; Mr Grice the self-educated steward; the briefly identified Hughling Elliot; and even a major figure such as Willoughby Vinrace, captain of the Euphrosyne, owner of the shipping line, and Rachel’s own father who disappears half way through the narrative, never to reappear.

It is not clear from the structure or the logic of the novel why Rachel has to die. There are no practical or thematic links to what has gone on before in the events of the narrative; nobody else is affected by the ‘fever’; and the conclusion of the novel (‘woman dies suddenly’) is not related to any of the previous events.

It is true that Woolf was surrounded by many unexpected deaths amongst her own friends and relatives (her mother, her brother, her friend Lytton Strachey) but this biographical connection does not provide a justification for the lack of a satisfactory resolution to the narrative.

The Voyage Out – study resources

![]() The Voyage Out – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

The Voyage Out – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Voyage Out – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

The Voyage Out – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Voyage Out – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

The Voyage Out – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Voyage Out – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

The Voyage Out – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

![]() The Voyage Out – Collins Classics – Amazon UK

The Voyage Out – Collins Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Voyage Out – Collins Classics – Amazon US

The Voyage Out – Collins Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Voyage Out – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

The Voyage Out – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Voyage Out – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

The Voyage Out – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Voyage Out – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

The Voyage Out – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Voyage Out – Kindle edition

The Voyage Out – Kindle edition

![]() Virginia Woolf – biographical notes

Virginia Woolf – biographical notes

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Virginia Woolf at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Mont Blanc pen – the Virginia Woolf special edition

The Voyage Out – plot summary

Chapter I. Ridley Ambrose and his wife Helen are leaving London to join their ship, the Euphrosyne which is due to take them on a cruise to South America. They join their niece, Rachel Vinrace, whose father owns the ship. A fellow traveller, Mr Pepper reminisces critically with Ambrose about their contemporaries at Cambridge. They are then joined by the captain Willoughby Vinrace.

Chapter II. The story switches between Helen’s reflections on Rachel, Mr Pepper’s bachelor interests and habits, and Mrs Chairley’s rage against the ship’s linens. It then covers Rachel’s lack of formal education, her talent for music, and her upbringing by aunts. She searches for coherence and meaning whilst she is critical of the adults who surround her.

Chapter III. In Portugal, Richard and Clarissa Dalloway are taken on board as extra passengers. At dinner there is conversation on the arts and politics, after which Clarissa writes a satirical letter criticising the other guests. Her husband joins her, and they both feel superior but sympathetic towards their fellow travellers.

Chapter IV. Clarissa meets Mr Grice, the self-educated steward, and then shares confidences with Rachel after breakfast. They read Jane Austen on deck, and Rachel discusses political philosophy with Richard Dalloway, who reveals his traditional and deep-seated male chauvinism.

Chapter V. The ship encounters a stormy passage at sea, which lays everybody low for two days. Helen comforts Mrs Dalloway with champagne. Meanwhile Richard Dalloway follows Rachel into her cabin and kisses her impulsively. That night Rachel has disturbing dreams.

Chapter VI. The Dalloways leave the ship. Rachel confides her mixed feelings about the incident to Helen, who advises her about Men and The Facts of Life. The two women agree to be friends, and Helen invites Rachel to stay at their villa whilst the captain sails up the Amazon, to which her father agrees for slightly selfish reasons.

Chapter VII. The ship reaches Santa Marina. Its colonial history is described. The Ambrose villa San Gervasio is dilapidated. After a week Mr Pepper decamps to a local hotel because he thinks the vegetables are not properly cooked at dinner.

Chapter VIII. Three months pass. Helen reflects on the inadequate education of young women. Helen and Rachel post letters then walk through the town to the hotel where they encounter guests playing cards. They are observed by Hirst and Hewet.

Chapter IX. In the hotel, people are preparing for the night. Hirst and Hewet discuss the possibility of organising a party excursion. Next day there is desultory chat over tea until Ridley Ambrose joins with Hirst and Hewet.

Chapter X. Rachel is reading modern literature and reflecting philosophically about the nature of life. She and Helen receive an invitation to Hewet’s expedition. The outing presents the radical young figure of Evelyn Murgatroyd, and Helen meets Terence Hewet,

Chapter XI. The party splits up at the top of the climb. Arthur declares his love to Susan. Their embraces are observed by Hewet and Rachel: she recoils ambivalently from the spectacle. They are joined by Hirst and Helen, whereupon they all agree to tell each other about themselves. The party then returns to town amidst a display of fireworks.

Chapter XII. A dance is held to celebrate Susan’s engagement to Arthur. Rachel is patronised then insulted by Hirst, whereupon Hewet makes excuses for him. Hirst then goes on to unburden himself to a sympathetic Helen. At dawn Hirst and Hewet walk back to the villa with Helen and Rachel.

Chapter XIII. Next day Rachel takes books by Balzac and Gibbon into the countryside to read, her mind full of impressions from the dance. She feels strangely moved by reading Gibbon, as if on the verge of some exciting discovery, and she thinks a lot about Hirst and Hewet.

Chapter XIV. Guests at the hotel read letters from friends and relatives back home. Susan is obsessed with the subject of marriage. Hewet can’t stop thinking about Rachel, and he goes up to the villa where he overhears her talking to Helen about her dead mother. He goes back to the hotel in a state of excitement, and is then quizzed by Evelyn about her flirtatious entanglements. Last thing at night he sees a woman coming out of someone’s bedroom.

Chapter XV. Some days later Helen and Ridley are visited by Mrs Flushing who is on a ‘collecting’ trip with her nouveau riche husband. They are joined by Hirst, Hewet, and Rachel who has tired of reading Gibbon. When Rachel and Hewet go for a walk, it leaves Hirst free to engage Helen in an intimate conversation, during which he reveals his fears and weaknesses, as well as expressing his admiration for her.

Chapter XVI. On their excursion Rachel and Hewet discuss the life of the typical unmarried middle-class girl (and its limitations) plus the issues raised by women’s suffrage. As he tells her about his literary ambitions she feels romantically attracted to him. He is excited yet dissatisfied by their intimacy and the tension between them.

Chapter XVII. Rachel is powerfully disturbed by her feelings for Hewet, and a distance grows between her and Helen. One Sunday there is a service in the hotel chapel. Rachel is distressed by the absence of any genuine religious belief, and she objects to the spirit in which the service is held. When Mrs Flushing invites her to lunch, she erupts into a criticism of the sermon. Mrs Flushing proposes a river trip to visit a traditional native village. Hirst and Hewet argue over religion, literature, and Rachel.

Chapter XVIII. Hewet realises that he is in love with Rachel, but he is in doubt about the idea of marriage. He wonders what her feelings are and cannot make up his mind about what to do.

Chapter XIX. Evelyn complains to Rachel about two men with whom she is romantically involved. Then she becomes enthusiastic about social reform – including the rescue of prostitutes. Rachel feels oppressed by her appeal to intimacy. She then meets Mrs Allan who invites her to her room and asks her to help her get dressed for tea. Rachel feels oppressed by this appeal too, and escapes into the garden, but she is irritated by the chatter and the discussion of plans for the excursion, and she then quarrells with Helen.

Chapter XX. The Flushings, along with Hewet and Hirst plus Rachel and Helen go on the expedition. They sail upstream in a small ship. Hewet is very conscious of Rachel’s presence. They go on a walk together in to the forest – to declare their love for each other. When they return to the ship they feel detached from their companions.

Chapter XXI. The expedition continues. Hewet and Rachel try to discuss the consequences of their love – which seem to lead inevitably towards marriage, about which neither of them is sure. The expedition reaches the native village. Hewet and Rachel are completely absorbed in each other. At night, back on the ship, they ask Helen for advice. She reassures them that they will be happy.

Chapter XXII. Hewet and Rachel become engaged. Whilst she plays the piano, he writes notes for his novel – on women, which reveal his traditional chauvinism. They plan their future and get to know about each other’s past lives. They become very nostalgic for England – both the countryside and London.

Chapter XXIII. Rachel is annoyed by people’s inquisitiveness now that she is engaged. A message from home brings news of the suicide of a housemaid. A ‘prostitute’ is expelled from the hotel. Hirst admits to himself that he is unhappy, but he brings himself to congratulate Hewet and Rachel.

Chapter XXIV. Sitting in the hotel, Rachel comes to an appreciation of her independent identity, even though she is joining herself to Hewet for the rest of her life. Miss Allan finishes her book on the English poets. Evelyn envies Susan and Rachel for being engaged, but she herself dreams of becoming a revolutionary.

Chapter XXV. Rachel develops a headache and is confined to her room. The headache gets worse and she becomes delirious. ‘Dr’ Rodriguez reassures them it is nothing serious, but Rachel gets steadily worse. Hirst is despatched in search of another doctor and returns with Dr Lesage. He confirms that Rachel is seriously ill – probably with fever. Hewet, Helen, and Hirst wait anxiously for days. Rachel starts to hallucinate, then eventually she dies.

Chapter XXVI. News of Rachel’s death quickly reaches the hotel. It is thought she was unwise to go on the expedition where she has caught the fever. Mr Perrot makes a final appeal to Evelyn, but she turns him down,, as she is leaving for Moscow.

Chapter XXVII. Life returns to normal at the hotel. There is a tropical thunderstorm, and people prepare to return home.

OUP World Classics edition

The Voyage Out – characters

| Mr Ridley Ambrose | a classics scholar, translating Pindar |

| Helen Ambrose | his wife (40) |

| Rachel Vinrace | their niece (24) |

| Willoughby Vinrace | a shipping line owner – Rachel’s father |

| Mr William Pepper | a dogmatic Cambridge friend of Ambrose |

| Mrs Emma Chairley | the Vinrace housekeeper (50) |

| Richard Dalloway | a former member of parliament (42) |

| Clarissa Dalloway | the daughter of a peer – his wife |

| Mr Grice | the self-educated steward |

| St John Hirst | a clever but boorish Cambridge don (24) |

| Terence Hewet | former student at Winchester and Cambridge |

| Evelyn Murgatroyd | a strong-willed feminist |

| Arthur Venning | a romantic young man |

| Susan Warrington | a romantic young woman |

| Wilfred Flushing | a nouveau riche art collector |

| Alice Flushing | his wife, an artist |

| Miss Allan | an elderly teacher of English |

| Mrs Thornbury | a wise old woman (72) |

| Dr Rodriguez | the (dubious) town doctor |

| Dr Lesage | the replacement doctor |

Virginia Woolf’s writing

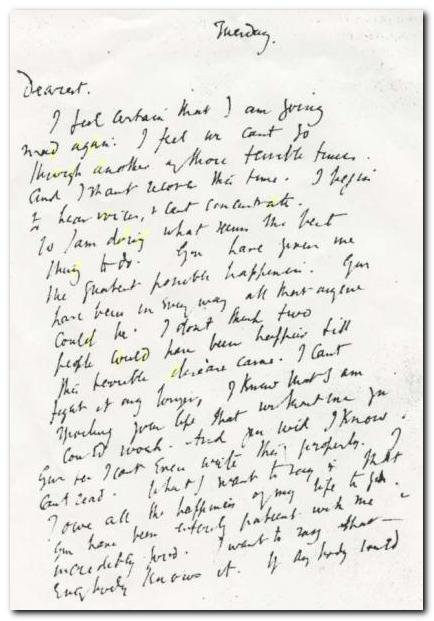

“I feel certain that I am going mad again.”

Other works by Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf – web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

Book reviews, Bloomsbury related issues, links, study resources, news of conferences, exhibitions, and events, regularly updated.

![]() Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of her work, fiction and non-fiction publications, photograph albumns, list of biographies, and external web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Selected eTexts of the novels The Voyage Out, Night and Day, Jacob’s Room, and the collection of stories Monday or Tuesday in a variety of digital formats.

![]() Woolf Online

Woolf Online

An electronic edition and commentary on To the Lighthouse with notes on its composition, revisions, and printing – plus relevant extracts from the diaries, essays, and letters.

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search texts of all the major novels and essays, word by word – locate quotations, references, and individual terms

![]() Virginia Woolf – a timeline in phtographs

Virginia Woolf – a timeline in phtographs

A collection of well and lesser-known photographs documenting Woolf’s life from early childhood, through youth, marriage, and fame – plus some first edition book jackets – to a soundtrack by Philip Glass. They capture her elegant appearance, the big hats, and her obsessive smoking. No captions or dates, but well worth watching.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury – including Gordon Square, Gower Street, Bedford Square, Tavistock Square, plus links to women’s history web sites.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Bulletins of events, annual lectures, society publications, and extensive links to Woolf and Bloomsbury related web sites

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

Charming sound recording of radio talk given by Virginia Woolf in 1937 – a podcast accompanied by a slideshow of photographs.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephen compiled a photograph album and wrote an epistolary memoir, known as the “Mausoleum Book,” to mourn the death of his wife, Julia, in 1895 – an archive at Smith College – Massachusetts

![]() Virginia Woolf first editions

Virginia Woolf first editions

Hogarth Press book jacket covers of the first editions of Woolf’s novels, essays, and stories – largely designed by her sister, Vanessa Bell.

![]() Virginia Woolf – on video

Virginia Woolf – on video

Biographical studies and documentary videos with comments on Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group and the social background of their times.

![]() Virginia Woolf Miscellany

Virginia Woolf Miscellany

An archive of academic journal essays 2003—2014, featuring news items, book reviews, and full length studies.

© Roy Johnson 2015

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group