notes and style guide for reviewers

notes and style guide for reviewers

1. Good book reviews should as a bare minimum be informative, but if they are good they will also be entertaining. Keep three things in mind whilst writing – your readers, the type of review, and the purpose of the review.

2. Your readers may be beginners – or advanced specialists. You should write reviews in different ways, according to the audience. A general reader will not have detailed technical knowledge. Advanced readers will want specialist information. The type of audience is likely to be determined by the publication – either in print or on the Web.

3. The kind of publication will also determine the type of review that is required. Popular newspapers and magazines have very short reviews – some as short as 100-200 words. Specialist journals might have reviews up to 2,000 words long. Make sure you have a clear idea of the type of review you are writing by getting to know the publication first.

4. The purpose of a review is to give an account of the subject in question (the book, film, play, or event) and offer a reasoned opinion about its qualities. Your main task is to report on the content, the approach, and the scope of the work for the benefit of your readers.

5. Even short reviews will be more successful if they have a firm structure. Here’s a bare-bones plan for a review:

- Brief introduction

- Description of contents

- Assessment of value

- Comparison with others

- Conclusion

6. Unless you are writing for a specialist journal, you should write in an easy reader-friendly manner.

7. Some publications give their reviewers scope for showing off or being controversial. (Pop music, restaurant, and television reviewers seem particularly prone to this.) In general however, you will be doing your readers a favour by putting their interests before your own.

8. If you are writing for the Web (in pages like these) remember to write in shorter sentences and shorter paragraphs than you would for a print publication. Reading extended prose on a computer screen is not easy. You will keep your reader’s attention by ‘chunking’ your information.

9. Apart from professional journalists, most reviewers do not get paid. However, you will get to keep the book, CD, or the object you are reviewing.

Review Structure

Here is the structure of a typical book review from this Mantex web site.

1. Title

2. Sub-title

3. One-sentence summary (ten words maximum)

4. Opening paragraph. This should be attention-grabbing, conversational in tone, and it might be slightly provocative. It’s purpose is to introduce the work under review – and to encourage the site visitor to read on. (Fifty words maximum)

5. Body of review. This will be a series of short paragraphs – around fifty words each in length. The total length of the review should be between 500 and 1,000 words – with longer reviews for exceptionally good or interesting works.

6. The review should give some account of the work’s positive qualities.

7. A typical review might take into account any of the following topics:

- What is the intended audience?

- Is it physically well produced?

- Is it pitched at the right level?

- Does it have any unusual features?

- What distinguishes it from similar publications of its type?

8. Concluding paragraph (fifty words maximum). This can summarise the reviewer’s opinion and may offer a personal flourish which echoes the introduction.

9. Full bibliographic details of the work under review – Author(s) – Title and Sub-title – Place of publication – Publisher – Date of publication – Number of pages – Full ISBN

10. The review should be accompanied by a graphic file of the book jacket or the software package design. These can be taken from the publisher’s site, or from Amazon.

Some Do’s and Don’ts

Do give examples

A brief quotation to illustrate good qualities of the work will brighten up your review. But keep it very short. Alternatively, use it as a ‘pull quote’. This is a statement which can appear separated from the main text of your review – placed in a box or highlighted in some way. These are usually chosen to capture the flavour of the work under review.

Don’t go on too long

Reviews which are short and to-the-point are more effective than ones which go on at great length. Unless you have lots of interesting things to say, readers will quickly become bored.

Don’t be over-negative

If you think something is entirely bad, then it’s probably not worth writing the review. After all, why bother giving publicity to bad work? There are only a couple of exceptions to this. One is if you wish to counter other reviews which you think have been mistaken or over-generous. The other is if the author is very well known and seems to you to have written badly. In such cases, make sure you give convincing reasons for your negative opinions – otherwise you risk seeming prejudiced.

How to write reviews of fiction

1. When reviewing fiction you are writing as an experienced reader, and your review is a personal response to your reading experience. A first person mode of address is permitted more than normal.

2. If possible you should consider the text in the context of the type or genre to which it belongs. It’s no good judging science fiction against the conventions of a traditional realist novel.

3. However, it always helps to have the full range of literary traditions in mind. If somebody writes about ‘floating islands’ you will look fairly silly if you don’t know that Jonathan Swift did it in 1726.

4. Give a brief summary of the plot – but don’t on any account give away any surprise or trick endings. You can say that the book ends in a dramatic or unexpected manner, but don’t spoil the reader’s pleasure.

5. Consider the book in the light of others of its kind. Is it offering something new, or just a variation on an old theme? Maybe the variation itself reflects some contemporary issue?

6. Comment on the quality of the writing. Is the prose style worthy of mention? Here is where a brief quotation can be very telling. Does the author do anything original in the way of presentation?

7. Are any large scale contemporary themes being explored? What are the underlying issues beneath the surface story-line? These may not be immediately evident, and sometimes authors write about one subject as a metaphor or a symbol for another.

8. Are the characters vividly portrayed and memorable? If so, try to give a brief example.

9. Has the author given obvious thought to the plot and the structure of the novel? Plot is usually easy to perceive, but structure can be a more difficult feature to isolate and describe.

10. You do not need to cover every detail of the book. It will be enough if you deal with the most important issues. Make your review as interesting as possible.

© Roy Johnson 2004

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

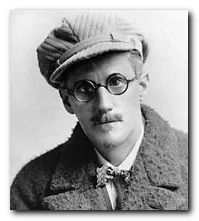

1882. James Joyce was born in Dublin, the eldest of ten children. His father was a rather improvident tax collector. The family became progressively impoverished.

1882. James Joyce was born in Dublin, the eldest of ten children. His father was a rather improvident tax collector. The family became progressively impoverished. James Joyce

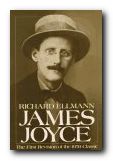

James Joyce The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book, London: Routledge, 1996.

Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book, London: Routledge, 1996. The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism. Dubliners is his first major work – a ground-breaking collection of short stories in which he strips away all the decorations and flourishes of late Victorian prose style. What remains is a sparse yet lyrical exposure of small moments of revelation – which he called ‘epiphanies’. Like other modernists, such as Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, Joyce minimised the dramatic element of the short story in favour of symbolic meaning and a more static aesthetic. This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century. The collection ends with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. It caused controversy when it first appeared, and was the first of many of Joyce’s works to be banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories. New readers should start here.

Dubliners is his first major work – a ground-breaking collection of short stories in which he strips away all the decorations and flourishes of late Victorian prose style. What remains is a sparse yet lyrical exposure of small moments of revelation – which he called ‘epiphanies’. Like other modernists, such as Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, Joyce minimised the dramatic element of the short story in favour of symbolic meaning and a more static aesthetic. This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century. The collection ends with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. It caused controversy when it first appeared, and was the first of many of Joyce’s works to be banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories. New readers should start here. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return. Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day. Finnegans Wake is famous in literary circles as a great novel which almost no one has ever read. Joyce said that he spent seventeen years of his life writing Finnegans Wake and that he expected readers to spend the rest of their lives trying to understand it. It continues where Ulysses leaves off in terms of linguistic complexity. Written and rewritten many times over, Joyce eventually decided to incorporate many languages other than English into the narrative. It is a fantastic crossword-puzzle of puns, parodies, jokes and linguistic invention which make enormous intellectual demands on the reader. This, in addition to the many arcane references and a very complex narrative make Finnegans Wake a literary experiment which has never been surpassed. It is one of the great unread masterpieces of twentieth century literature.

Finnegans Wake is famous in literary circles as a great novel which almost no one has ever read. Joyce said that he spent seventeen years of his life writing Finnegans Wake and that he expected readers to spend the rest of their lives trying to understand it. It continues where Ulysses leaves off in terms of linguistic complexity. Written and rewritten many times over, Joyce eventually decided to incorporate many languages other than English into the narrative. It is a fantastic crossword-puzzle of puns, parodies, jokes and linguistic invention which make enormous intellectual demands on the reader. This, in addition to the many arcane references and a very complex narrative make Finnegans Wake a literary experiment which has never been surpassed. It is one of the great unread masterpieces of twentieth century literature.