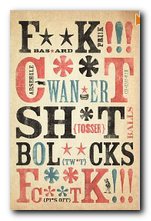

The How, Why, When, and What of Everyday Swearing

Dictionaries of slang and obscenity are often disappointing, because they define terms but shy away from discussing exactly how they are used in everyday life. Filthy English does the opposite. Peter Silverton not only tells you what swear words mean, but he illustrates and analyses their use in the very places for which they are designed – the street, the pub, the argument, the curse, and the insult. His analysis of swearing is delivered via an account of his own relation to language in 1950s UK and beyond.

The story goes down endless numbers of digressions – but fortunately he has an amusing and lively style, full of witty asides and one-liners. (“People from Maidenhead never laugh when telling you where they live”) This personal history spreads out into a very well-informed history of the words he is considering. But the humour is underpinned by a very scholarly sense of etymology.

The story goes down endless numbers of digressions – but fortunately he has an amusing and lively style, full of witty asides and one-liners. (“People from Maidenhead never laugh when telling you where they live”) This personal history spreads out into a very well-informed history of the words he is considering. But the humour is underpinned by a very scholarly sense of etymology.

He follows the well-worn tradition of presenting his observations in cod-serious, satirically po-faced categories: Chapter One – ‘Sexual intercourse and Masturbation’; Chapter Two – ‘Anuses, Faeces, Urine, and Other Excreta’. This makes what he has to say all the funnier.

He has a finely attuned ear for the subtleties of language, and spends a number of pages discussing the fine distinctions between calling someone a wanker or a tosser – despite the fact that the words appear to mean the same thing. He brings a sociological as well as an etymological knowledge to his analysis

What also makes this approach so attractive is that he is steeped in the popular culture of the last forty or fifty years in Britain. He recaptures some of its pivotal linguistic moments in vividly entertaining anecdotes from the world of television, sport, pop music, and political life.

He also considers very carefully the shock value or taboo-quotient on well known swear words (or swears as he calls them) as well as pointing to absurdities such as the fact that many people would find “Bugger that!” (anal intercourse) far less offensive than “Fuck that!” (normal sexual intercourse). This is matched by his intelligent sense of the history of language change and development:

Once we were a religious society and ‘damn’ was the word that could tear into our social and emotional fabric. As the Enlightenment edged religion aside, so sexuality became the locus of swear-power – fuck starting its rise in the nineteenth century, followed by cunt in the second half of the twentieth. Now it’s the nouns and epithets of group identity that are taking over – race words mostly, but also ones about religion and class.

It’s quite surprising how rapidly the meaning of a word can change. Spunk was originally the name for touch-wood, the stuff people carried round for starting fires. Then from the eighteenth century onwards it meant courage or bravery:

It was only in the late nineteenth century that the possession of those qualities came to be transferred to the quintessentially liquid expression of masculinity. It’s an intriguing psychological correlation: heroism and the vector of male DNA transmission. Jamaicans call it man juice.

He’s amazingly well informed on swearing in a number of languages from all over the world – which serves well to demonstrate the universality of the phenomenon. And he includes ‘hidden’ languages such as ‘mother-in-law languages’ (a form of avoidance speech) and the Russian unofficial language Mat (older than Russian language itself) which is based upon only four or five words and their infinite variations.

I was also glad to see that he’s smack up to date. In his discussion of the term ‘gay’ he notes that it’s rapidly becoming a general term of gentle teasing, in addition to its conventional use as a synonym for homosexual. One man invites his male friend out for a drink, only to be told he’s tired and wants to stay in. “Don’t be so gay” might be the response.

He finishes with a bravura excursion into psycho-analysis, where with an examination of what Freud and Ferenczi had to say about forbidden language adds up to the fact that these swear words are deeply attached to the most important parts of our bodies. People with Tourette’s Syndrome don’t shout out “Ankles! Shoulders! Opposite sex!”. They shout “Cock! Cunt! Fuck!”

For anyone interested in demotic language, this is a must. Silverton is entertaining from first page to last – and his apercus are backed up with erudition, scholarship, but more importantly with a healthy engagement with the language of everyday life on the streets of the UK and the rest of the world today.

© Roy Johnson 2011

Peter Silverton, Filthy English: The How, Why, When, and What of Everyday Swearing, London: Portobello Books, 2010, pp.314, ISBN: 184627169X

More on dictionaries

More on language

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

The Little Oxford Dictionary

The Little Oxford Dictionary

The New Oxford Dictionary

The New Oxford Dictionary

The Compact OED

The Compact OED