creating firm structure and clear argument

1. Essay plans

You can approach the composition of an essay using a number of different writing strategies. Some people like to start writing and wait to see what develops. Others work up scraps of ideas until they perceive a shape emerging. However, if you are in any doubt at all, it’s a good idea to create essay plans for your work. The task of writing is usually much easier if you create a set of notes which outline the points you are going to make. Using this approach, you will create a basic structure on which your ideas can be built.

2. Planning techniques

This is a part of the essay-writing process which is best carried out using plenty of scrap paper. Get used to the idea of shaping and re-shaping your ideas before you start writing, editing and rearranging your arguments as you give them more thought. Planning on-screen using a word-processor is possible, but it’s a fairly advanced technique.

3. Analyse the question

Make sure you understand what the question is asking for. What is it giving you the chance to write about? What is its central issue? Analyse any of its key terms and any instructions. If you are in any doubt, ask your tutor to explain what is required.

4. Generate ideas

You need to assemble ideas for the essay. On a first sheet of paper, make a note of anything which might be relevant to your answer. These might be topics, ideas, observations, or instances from your study materials. Put down anything you think of at this stage.

5. Choosing topics

On a second sheet of paper, extract from your brainstorm listings those topics and points of argument which are of greatest relevance to the question and its central issue. Throw out anything which cannot be directly related to the essay question.

6. Put topics in order

On a third sheet of paper, put these chosen topics in some logical sequence. At this stage you should be formulating a basic response to the question, even if it is provisional and may later be changed. Try to arrange the points so that they form a persuasive and coherent argument.

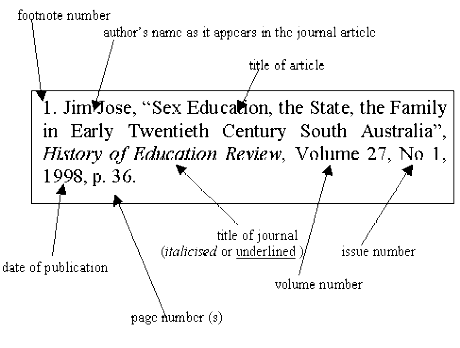

7. Arrange your evidence

All the major points in your argument need to be supported by some sort of evidence. On any further sheets of paper, compile a list of brief quotations from other sources (together with page references) which will be offered as your evidence.

8. Make necessary changes

Whilst you have been engaged in the first stages of planning, new ideas may have come to mind. Alternate evidence may have occurred to you, or the line of your argument may have shifted somewhat. Be prepared at this stage to rearrange your plan so that it incorporates any of these new materials or ideas. Try out different arrangements of your essay topics until you are sure they form the most convincing and logical sequence.

9. Finalise essay plan

The structure of most essay plans can be summarised as follows:

Introduction

Arguments

Conclusion

State your case as briefly and rapidly as possible, present the evidence for this case in the body of your essay, then sum up and try to ‘lift’ the argument to a higher level in your conclusion. Your final plan should be something like a list of half a dozen to ten major points of argument. Each one of these points will be expanded to a paragraph of something around 100-200 words minimum in length.

10. Relevance

At all stages of essay planning, and even when writing the essay, you should keep the question in mind. Keep asking yourself ‘Is this evidence directly relevant to the topic I have been asked to discuss?‘ If in doubt, be prepared to scrap plans and formulate new ones – which is much easier than scrapping finished essays. At all times aim for clarity and logic in your argument.

11.Example

What follows is an example of an outline plan drawn up in note form. It is in response to the question ‘Do you think that depictions of sex and violence in the media should or should not be more heavily censored?‘. [It is worth studying the plan in its entirety. Take note of its internal structure.]

Sample essay plan

Question

‘Do you think that depictions of sex and violence in the media should or should not be more heavily censored?‘

Introduction

Sex, violence, and censorship all emotive subjects

Case against censorship

1. Aesthetic: inhibits artistic talent, distorts art and truth.

2. Individual judgement: individuals have the right to decide for

themselves what they watch or read. Similarly, nobody has the right to make up someone else’s mind.

3. Violence and sex as catharsis (release from tension): portrayal of these subjects can release tension through this kind of experience at ‘second hand’.

4. Violence can deter: certain films can show violence which

reinforces opposition to it, e.g. – A Clockwork Orange, All Quiet on the Western Front.

5. Censorship makes sex dirty: we are too repressed about this

subject, and censorship sustains the harmful mystery which has surrounded us for so long.

6. Politically dangerous: Censorship in one area can lead to it

being extended to others – e.g., political ideas.

7. Impractical: Who decides? How is it to be done? Is it not

impossible to be ‘correct’? Any decision has to be arbitrary

Case for censorship

1. Sex is private and precious: it should not be demeaned by

representations of it in public.

2. Sex can be offensive: some people may find it so and should not have to risk being exposed to what they would find pornographic.

3. Corruption can be progressive: can begin with sex and continue until all ‘decent values’ are eventually destroyed.

4. Participants might be corrupted: especially true of young

children.

5. Violence can encourage imitation: by displaying violence – even while condemning it -it can be legitimised and can also encourage

imitation amongst a dangerous minority.

6. Violence is often glorified: encourages callous attitudes.

Conclusion

Case against censorship much stronger. No necessary connection between the two topics.

© Roy Johnson 2004

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills