novels, novellas, short stories, criticism

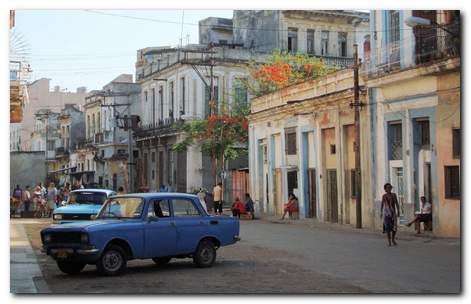

Alejo Carpentier (1904-1980) was a Cuban writer who made a connection between European culture and the native history of Latin-America. His literary style is a wonderful combination of dazzling images and a rich language, full of the technical jargon of whatever subject he touches on – music, architecture, painting, history, or agriculture.

He was also the first to use the techniques of ‘magical realism’ (he coined the term, lo real maravilloso) in which the concrete, real world becomes suffused with fantasy elements, myths, dreams, and a fractured sense of time and logic.

Carpentier is generally considered one of the fathers of modern Latin American literature. His complex, baroque style has inspired such writers as Gabriel García Márquez and Carlos Fuentes.

Alejo Carpentier – novels in English

![]() The Kingdom of this World (1949) – Amazon UK

The Kingdom of this World (1949) – Amazon UK

![]() The Kingdom of this World (1949) – Tutorial, study guide, web links

The Kingdom of this World (1949) – Tutorial, study guide, web links

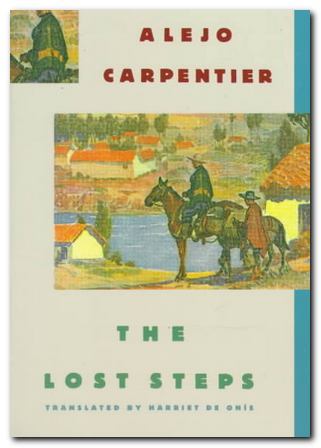

![]() The Lost Steps (1953) – Amazon UK

The Lost Steps (1953) – Amazon UK

![]() The Lost Steps (1953) – Tutorial, study guide, web links

The Lost Steps (1953) – Tutorial, study guide, web links

![]() Explosion in a Cathedral (1962) – Amazon UK

Explosion in a Cathedral (1962) – Amazon UK

![]() Reasons of State (1974) – Amazon UK

Reasons of State (1974) – Amazon UK

![]() The Consecration of Spring (1978) – Amazon UK

The Consecration of Spring (1978) – Amazon UK

![]() The Harp and the Shadow (1979) – Amazon UK

The Harp and the Shadow (1979) – Amazon UK

![]() The Harp and the Shadow (1979) – Tutorial, study guide, web links

The Harp and the Shadow (1979) – Tutorial, study guide, web links

Alejo Carpentier – stories in English

![]() The Chase (1956) – Amazon UK

The Chase (1956) – Amazon UK

![]() The Chase (1956) – Tutorial and study guide

The Chase (1956) – Tutorial and study guide

![]() The War of Time (1963) – Amazon UK

The War of Time (1963) – Amazon UK

![]() Journey Back to the Source (1963) – Amazon UK

Journey Back to the Source (1963) – Amazon UK

![]() Journey Back to the Source (1963) – Tutorial and study guide

Journey Back to the Source (1963) – Tutorial and study guide

![]() The Road to Santiago (1963) – Amazon UK

The Road to Santiago (1963) – Amazon UK

![]() The Road to Santiago (1963) – Tutorial and study guide

The Road to Santiago (1963) – Tutorial and study guide

![]() Right of Sanctuary (1967) – Amazon UK

Right of Sanctuary (1967) – Amazon UK

![]() Right of Sanctuary (1967) – Tutorial and study guide

Right of Sanctuary (1967) – Tutorial and study guide

![]() Baroque Concerto (1974) – Amazon UK

Baroque Concerto (1974) – Amazon UK

![]() Baroque Concerto (1974) – Tutorial and study guide

Baroque Concerto (1974) – Tutorial and study guide

Alejo Carpentier – novels in Spanish

![]() Ecue-yamba-O! (1933) – Amazon UK

Ecue-yamba-O! (1933) – Amazon UK

![]() El reino de este mundo (1949) – Amazon UK

El reino de este mundo (1949) – Amazon UK

![]() Los pasos perdidos (1953) – Amazon UK

Los pasos perdidos (1953) – Amazon UK

![]() El siglo de las luces (1962) – Amazon UK

El siglo de las luces (1962) – Amazon UK

![]() El recurso del metodo (1974) – Amazon UK

El recurso del metodo (1974) – Amazon UK

![]() La consegracion de la primavera (1978) – Amazon UK

La consegracion de la primavera (1978) – Amazon UK

![]() El arpa y el sombra (1979) – Amazon UK

El arpa y el sombra (1979) – Amazon UK

![]() Cuentos completos (1979) – Amazon UK

Cuentos completos (1979) – Amazon UK

Alejo Carpentier web links

![]() Carpentier at Wikipedia

Carpentier at Wikipedia

Background, biography, magical realism, major works, literary style, further reading

![]() Carpentier at Amazon UK

Carpentier at Amazon UK

Novels, criticism, and interviews – in Spanish and English

![]() Carpentier at Internet Movie Database

Carpentier at Internet Movie Database

Films and TV movies made from his novels

![]() Carpentier in Depth

Carpentier in Depth

Spanish video documentary and interview with Carpentier (1977)

© Roy Johnson 2017

More on Alejo Carpentier

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Alejo Carpentier was a Cuban writer who straddled the connection between European literature and the native culture of Latin-America. He was for a long time the Cuban cultural ambassador in Paris. Carpentier was trying to place Latin-American culture into a historical context. This was done via a conscious depiction of the colonial past – as in The Kingdom of This World, and Explosion in a Cathedral (title in Spanish El Siglo de las Luces – or The Age of Enlightenment).

Alejo Carpentier was a Cuban writer who straddled the connection between European literature and the native culture of Latin-America. He was for a long time the Cuban cultural ambassador in Paris. Carpentier was trying to place Latin-American culture into a historical context. This was done via a conscious depiction of the colonial past – as in The Kingdom of This World, and Explosion in a Cathedral (title in Spanish El Siglo de las Luces – or The Age of Enlightenment). The Kingdom of This World

The Kingdom of This World The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps Explosion in a Cathedral

Explosion in a Cathedral The Chase

The Chase