illustrated review of contemporary architectural design

The previous edition of this series, Architecture Now!, was the winner of the prestigious Saint-Etienne Prize for the Best Architecture and Design Book of 2004. Now volume four brings an even more spectacular portfolio of contemporary architecture and design to a general readership via Taschen’s policy of high quality publications at budget prices. The selection here is quite breathtaking. Projects range from multi-million pound buildings to humble constructions such as a tree house, a loft extension, and a prototype for sheltered housing made out of sandbags.

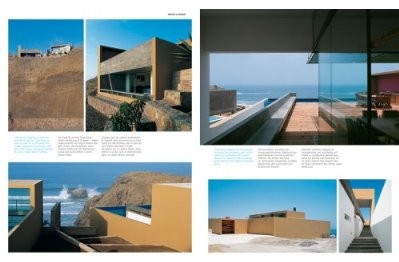

There’s an exhibition centre built out of old shipping containers, a water purification plant, and one spectacular private commission for a house built on a cliff top with a suspended swimming pool which looks as if it is floating in mid-air.

There’s an exhibition centre built out of old shipping containers, a water purification plant, and one spectacular private commission for a house built on a cliff top with a suspended swimming pool which looks as if it is floating in mid-air.

Each entry presents full contact details for the featured architects, including their web sites, many of which are works of art in their own right. The text is in three languages – English, French, and German – but the emphasis is emphatically upon visual presentation. Beautiful high-quality photographs bring out in full the contrasting textures of materials such as plate glass, brick and natural stone, water, concrete, and polished copper.

You’ve got to be on your visual toes, because some of the projects only exist as models and mock-ups; but they are rendered using digital techniques which blend natural landscapes with computer-generated images in such a way that you’d swear you were looking at a finished construction.

The selection includes all the well known names you would expect to find in a survey of this kind – Frank O Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, and Saha Hadid. But I was surprised the editor Philipe Jodidio did not include Richard Rogers, Norman Forster, Nicholas Grimshawe, or Renzo Piano. Yet strangely enough he does include work by the video installation artist Bill Viola and the painter Frank Stella, who has recently produced some sculpture with architectural forms.

I was pleased to note that Jodidio does not shy away from discussing the costs of some of these projects – many of which have notoriously run many times over budget. You get the feeling that he has not put his critical faculties on hold whilst he celebrates the obvious creativity on show. And he introduces some interesting concepts and techniques – such as ‘topographic insertion’, in which a construction is merged with its surrounding landscape.

This is a marvelously stimulating production which will appeal to anybody interested in modern building and design, and in particular those who are concerned with the integration of man-made environments into the natural world.

© Roy Johnson 2006

Philipe Jodidio (ed), Architecture Now! V.4, London: Taschen, 2006, pp.576, ISBN 3822839892

More on architecture

More on technology

More on design