a guide to Conrad’s classic critique of imperialism

Joseph Conrad retired from the sea and started writing romantic adventure stories. His first works were popular but light, but then in 1899 he produced a novella which struck such dark tones and offered a reading of European imperialism so profound, that it still strikes deep resonances today. Heart of Darkness, which is aimed at students and general readers who might wish to extend their understanding of Conrad and what he has to offer. The first chapter puts Conrad into historical, intellectual, cultural, and literary context. He was of the nineteenth century, but he signalled many of the concerns and even the literary techniques of twentieth century modernism. And of course, even though he is now regarded as a pillar stone of English Literature, he was Polish.

This is a study guide to that work, Allan Simmons then takes you straight into an analysis of the story via his consideration of Conrad’s use of English (which was his third language) his narrator Marlow, and his use of the novella as a literary form. A level students and undergraduates will find his analyses of the details thought-provoking – and the process should lead them towards the complexities of investigation they might be making on their own behalf. At the same time, anyone teaching the novella will find his approach useful.

This is a study guide to that work, Allan Simmons then takes you straight into an analysis of the story via his consideration of Conrad’s use of English (which was his third language) his narrator Marlow, and his use of the novella as a literary form. A level students and undergraduates will find his analyses of the details thought-provoking – and the process should lead them towards the complexities of investigation they might be making on their own behalf. At the same time, anyone teaching the novella will find his approach useful.

The central part of the book is a reading of the novella, tracing the narrator Marlow’s journey from Europe, into the ‘dark continent’, and back out again – an ambiguously changed man. Simmons traces all the subtle allusions, symbols, and thematic parallels in the narrative.

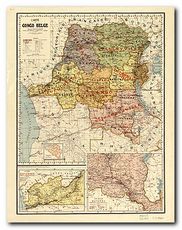

Despite the ultimate pointlessness of comparing fiction with what might have been its real life inspiration, I think a map of the Congo would have been useful here.

In the two final chapters Simmons traces Conrad’s reputation as a writer from the publication of Heart of Darkness to the present, then he looks at the adaptations – nearly ninety films and even a piano concerto.

There is still interpretive work to be done on many aspects of Conrad – not least his attitude to women – but studies such as this help to provide the means whereby this work will be done.

© Roy Johnson 2007

Allan Simmons, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, London: Continuum, 2007, pp.132, ISBN: 0826489346

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

More on Joseph Conrad tales

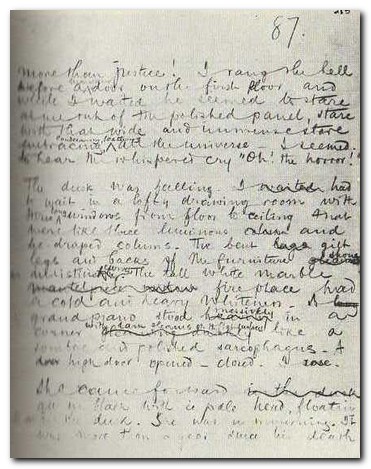

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes Almayer’s Folly

Almayer’s Folly An Outcast of the Islands

An Outcast of the Islands Lord Jim

Lord Jim Nostromo

Nostromo Chance

Chance Victory

Victory

Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912) is a classic novella – half way between a long story and a short novel. It’s a wonderfully condensed tale of the relationship between art and life, love and death. Venice provides the background for the story of a famous German writer who departs from his usual routines, falls in love with a young boy, and gets caught up in a subtle downward spiral of indulgence. The novella is constructed on a framework of references to Greek mythology, and the unity of themes, form, and motifs are superbly realised – even though Mann wrote this when he was quite young. Later in life, Mann was to declare – ‘Nothing in Death in Venice was invented’. The story was turned into a superb film by Luchino Visconti and an opera by Benjamin Britten.

Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912) is a classic novella – half way between a long story and a short novel. It’s a wonderfully condensed tale of the relationship between art and life, love and death. Venice provides the background for the story of a famous German writer who departs from his usual routines, falls in love with a young boy, and gets caught up in a subtle downward spiral of indulgence. The novella is constructed on a framework of references to Greek mythology, and the unity of themes, form, and motifs are superbly realised – even though Mann wrote this when he was quite young. Later in life, Mann was to declare – ‘Nothing in Death in Venice was invented’. The story was turned into a superb film by Luchino Visconti and an opera by Benjamin Britten. Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd (1856) deals with a tragic incident at sea, and is based on a true occurence. It is a nautical recasting of the Fall, a parable of good and evil, a meditation on justice and political governance, and a searching portrait of three men caught in a deadly triangle. Billy is the handsome innocent, Claggart his cruel tormentor, and Captain Vere the man who must judge in the conflict between them. The narrative is variously interpreted in Biblical terms, or in terms of representations of male homosexual desire and the mechanisms of prohibition against this desire. His other great novellas Benito Cereno, The Encantadas and Bartelby the Scrivener (all in this collection) show Melville as a master of irony, point-of-view, and tone. These fables ripple out in nearly endless circles of meaning and ambiguities.

Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd (1856) deals with a tragic incident at sea, and is based on a true occurence. It is a nautical recasting of the Fall, a parable of good and evil, a meditation on justice and political governance, and a searching portrait of three men caught in a deadly triangle. Billy is the handsome innocent, Claggart his cruel tormentor, and Captain Vere the man who must judge in the conflict between them. The narrative is variously interpreted in Biblical terms, or in terms of representations of male homosexual desire and the mechanisms of prohibition against this desire. His other great novellas Benito Cereno, The Encantadas and Bartelby the Scrivener (all in this collection) show Melville as a master of irony, point-of-view, and tone. These fables ripple out in nearly endless circles of meaning and ambiguities. Artistically, the novella is often unified by the use of powerful symbols which hold together the events of the story. The novella requires a very strong sense of form – that is, the shape and essence of what makes it distinct as a literary genre. It is difficult to think of a great novella which has not been written by a great novelist (though Kate Chopin’s The Awakening might be considered an exception). Another curious feature of the novella is that it is almost always very serious. It’s equally difficult to think of a great comic novella – though Saul Bellow’s excellent Seize the Day has some lighter moments.

Artistically, the novella is often unified by the use of powerful symbols which hold together the events of the story. The novella requires a very strong sense of form – that is, the shape and essence of what makes it distinct as a literary genre. It is difficult to think of a great novella which has not been written by a great novelist (though Kate Chopin’s The Awakening might be considered an exception). Another curious feature of the novella is that it is almost always very serious. It’s equally difficult to think of a great comic novella – though Saul Bellow’s excellent Seize the Day has some lighter moments. Seize the Day (1956) focusses on one day in the life of one man, Tommy Wilhelm. A fading charmer who is now separated from his wife and his children, he has reached his day of reckoning and is scared. In his forties, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. Some people might wish to argue that this is a short novel, but it is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a novella. It is now generally regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works, even though he went on to write a number of successful and much longer novels – for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976.

Seize the Day (1956) focusses on one day in the life of one man, Tommy Wilhelm. A fading charmer who is now separated from his wife and his children, he has reached his day of reckoning and is scared. In his forties, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. Some people might wish to argue that this is a short novel, but it is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a novella. It is now generally regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works, even though he went on to write a number of successful and much longer novels – for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976. Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1897) is a classic novella, and a ghost story which defies easy interpretation. A governess in a remote country house is in charge of two children who appear to be haunted by former employees who are now supposed to be dead. But are they? The story is drenched in complexities – including the central issue of the reliability of the person who is telling the tale. This can be seen as a subtle, self-conscious exploration of the traditional haunted house theme in Victorian culture, filled with echoes of sexual and social unease. Or is it simply, “the most hopelessly evil story that we have ever read”? This collection also includes James’s other ghost stories – Sir Edmund Orme, Owen Wingrave, and The Friends of the Friends.

Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1897) is a classic novella, and a ghost story which defies easy interpretation. A governess in a remote country house is in charge of two children who appear to be haunted by former employees who are now supposed to be dead. But are they? The story is drenched in complexities – including the central issue of the reliability of the person who is telling the tale. This can be seen as a subtle, self-conscious exploration of the traditional haunted house theme in Victorian culture, filled with echoes of sexual and social unease. Or is it simply, “the most hopelessly evil story that we have ever read”? This collection also includes James’s other ghost stories – Sir Edmund Orme, Owen Wingrave, and The Friends of the Friends. The Aspern Papers (1888) also by Henry James, is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s private correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer seeks a husband for her plain niece, whereas the potential purchaser of the letters she possesses is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who wins out? Henry James keeps readers guessing until the very end. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in the outcome. This collection of stories also includes The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion which is another classic novella.

The Aspern Papers (1888) also by Henry James, is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s private correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer seeks a husband for her plain niece, whereas the potential purchaser of the letters she possesses is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who wins out? Henry James keeps readers guessing until the very end. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in the outcome. This collection of stories also includes The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion which is another classic novella. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of late nineteenth century imperialism and the colonial process. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement. It is certainly regarded as a classic of the novella form, and a high point of twentieth century literature – even though it was written at its beginning. This volume also contains the story An Outpost of Progress – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’. The differences between a story and a novella are readily apparent here if you read both texts and compare them.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of late nineteenth century imperialism and the colonial process. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement. It is certainly regarded as a classic of the novella form, and a high point of twentieth century literature – even though it was written at its beginning. This volume also contains the story An Outpost of Progress – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’. The differences between a story and a novella are readily apparent here if you read both texts and compare them. Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis is the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. His family are bewildered, find it difficult to deal with him, and despite the good human intentions struggling underneath his insect carapace, they eventually let him die of neglect. He eventually expires with a rotting apple lodged in his side. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s other masterly transformations of the short story form – ‘The Great Wall of China’, ‘Investigations of a Dog’, ‘The Burrow’, and the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’.

Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis is the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. His family are bewildered, find it difficult to deal with him, and despite the good human intentions struggling underneath his insect carapace, they eventually let him die of neglect. He eventually expires with a rotting apple lodged in his side. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s other masterly transformations of the short story form – ‘The Great Wall of China’, ‘Investigations of a Dog’, ‘The Burrow’, and the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’.