tutorial, commentary, study resources, video, and web links

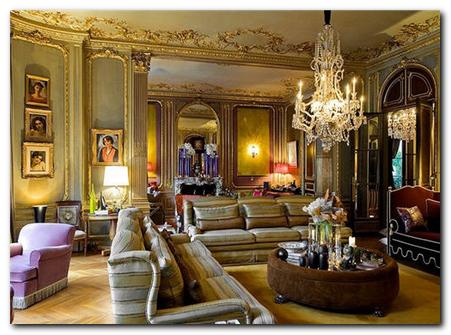

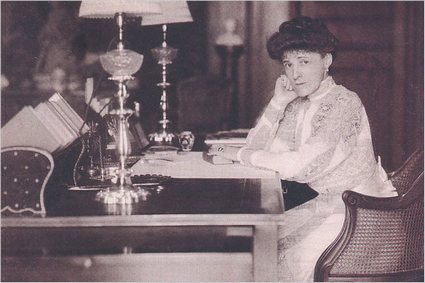

The Age of Innocence (1920) is perhaps Edith Wharton’s most famous novel. It was written immediately after the First World War, when she had settled permanently to live just outside Paris. She takes as her subject three issues she knew very well from first-hand experience: old New York upper-class society of the 1870s, marriage, and divorce. She had been encouraged to take this as her material by her friend Henry James, who urged her to ‘do’ old New York. And like James she also included as a substantial fourth subject, the tensions between European and American culture.

first edition dust cover 1920

The Age of Innocence – plot summary

Part I

Newland Archer is a rather conventional member of ‘old money’ New York society. He works half-heartedly in a legal firm and has just become engaged to May Welland, who is also a member of a respectable family. Into this group there suddenly appears Countess Ellen Olenska, an American who has separated from her Polish husband. Archer and his set try to arrange a dinner to integrate Ellen into New York society, but they receive refusals on the unspoken grounds that she is not respectable because of her tainted past. So her relatives appeal to one of the oldest families, the Van der Luydens, who invite Ellen to meet a visiting English Duke. The occasion is a social success, and it provides Ellen with the seal of approval she needs.

Archer visits Ellen (at her request) and is impressed by her bohemianism and her radical attitudes. He feels increasingly stifled by the expectations of his family and what he sees as the dull predictability of the married life ahead of him. Almost unknown to himself, he is attracted to Ellen and what she represents as a free spirit. Archer is asked by his law firm to handle the case Ellen wishes to bring against her husband for divorce. New York society prefers to avoid such a scandal, and Archer is successful in managing to persuade her against the action.

Archer visits Ellen (at her request) and is impressed by her bohemianism and her radical attitudes. He feels increasingly stifled by the expectations of his family and what he sees as the dull predictability of the married life ahead of him. Almost unknown to himself, he is attracted to Ellen and what she represents as a free spirit. Archer is asked by his law firm to handle the case Ellen wishes to bring against her husband for divorce. New York society prefers to avoid such a scandal, and Archer is successful in managing to persuade her against the action.

When his fiancee May goes south for a winter holiday, Archer follows Ellen to a weekend in the country, but their intimacy is spoiled by the arrival of Julius Beaufort, of whom Archer feels jealous. Archer then abruptly visits May on her holiday, where he tries to convince himself that he still wants to marry her. He asks her to bring their marriage date forward. She wonders if there is somebody else in Archer’s life – and he is relieved to discover that she is thinking of someone in his distant past.

Returning to New York, Archer finally manages to arrange a private audience with Ellen, whereupon he declares his love for her. She reciprocates his feelings but argues that having provided her with his protective friendship, he should now stand by his engagement to May. She feels it would be dishonourable to take advantage of people who have shown her friendship. On returning home he receives a telegram from May announcing that she will marry him in a month’s time.

Part II

On his wedding day Archer is oppressed by the weight of expectancy and tradition that he realises marriage will entail. Even on his honeymoon he also realises that there is an emotional and intellectual gulf between himself and May – though he realises that she is likely to be a good and loyal wife.

He continues to be disturbed by visions of Ellen. He follows her to Boston where she has just turned down an offer to re-join her husband. Over a private lunch they agree that they must stay separate and love each other from a distance. Archer also meets Count Olenski’s emissary, who pleads that Ellen should remain in America, and reveals that Archer’s family now want her to return to her husband.

Beaufort’s bank crashes, which indirectly affects Archer’s family. At the same time the family dowager matriarch Mrs Mingott has a stroke. Ellen is summoned from a retreat in Washington to live with her and provide support. Archer proposes to Ellen that they should commit themselves to each other in some sort of alliance, but she refuses on the grounds that this would put them both outside society. She finally suggests to him that they spend just one night together before she returns to Europe.

The love tryst fails to materialize, and Ellen is given a send-off dinner, at which Archer realises that everybody believes that he and Ellen are lovers. This is their way of getting rid of the social problem without even officially recognising it. Archer has decided to follow Ellen to Europe, but when he attempts to confess all to May, she reveals that she is pregnant, and has told Ellen about it earlier.

Twenty-six years later, after a faultless life of public service, Archer is visiting Paris with his son Dallas, who has made an appointment to visit his relation Countess Olenska, who still lives on the Left Bank. Dallas reveals that his mother (as she was dying) told him about the relationship between Archer and Ellen. Archer despatches his son to meet Ellen, but does not go himself.

The Age of Innocence – study resources

![]() The Age of Innocence – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

The Age of Innocence – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Age of Innocence – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

The Age of Innocence – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Age of Innocence – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

The Age of Innocence – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Age of Innocence – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

The Age of Innocence – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Age of Innocence – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Age of Innocence – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Age of Innocence – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Age of Innocence – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Age of Innocence – Cliff’s Notes study guide – Amazon UK

The Age of Innocence – Cliff’s Notes study guide – Amazon UK

![]() The Age of Innocence – Norton Critical Editions – Amazon US

The Age of Innocence – Norton Critical Editions – Amazon US

![]() The Age of Innocence – eBook formats at Gutenberg

The Age of Innocence – eBook formats at Gutenberg

![]() The Age of Innocence – audioBook version at Gutenberg

The Age of Innocence – audioBook version at Gutenberg

![]() The Age of Innocence – Kindle eBook edition

The Age of Innocence – Kindle eBook edition

![]() A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

Principal characters

| Newland Archer | a young well-to-do ‘gentleman lawyer’ |

| Mrs Adeline Archer | his old-fashioned mother |

| Janey Archer | his sister, an old-fashioned virgin |

| Mr Welland | an advanced valetudinarian |

| Mrs Welland | May’s mother |

| May Welland | Archer’s fiancee |

| Lawrence Lefferts | adulterous man-about-town, friend of Archer |

| Mr Sillerton Jackson | an authority on ‘old society’, ‘the drawing room moralist’ |

| Miss Sophy Jackson | his sister |

| Mrs Manson Mingott | a rich and obese New York dowager matriarch |

| Lovell Mingott | her son |

| Julius Beaufort | an English banker of doubtful provenance |

| Van der Luydens | old New York society family |

| Mrs Lemuel Struthers | raffish nouveau riche |

| Duke of St Austrey | shabby and comic English toff |

| Ned Winsett | journalist on woman’s weekly magazine, friend of Archer |

| Mrs Thorley Rushworth | Archer’s former married lover |

| Count Stanislas Olenski | Ellen’s Polish husband |

| Marchioness Medora Manson | Ellen’s flambouyant and eccentric aunt |

| Dr Agathon Carver | a fashionable spiritualist |

| Mr Riviére | personal tutor and emissary of Count Olenski |

The Age of Innocence – Video

1993 adaptation by Martin Scorsese

Further reading

Louis Auchincloss, Edith Wharton: A Woman of her Time, New York: Viking, 1971,

Elizabeth Ammons, Edith Wharton’s Argument with America, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1982, pp.222. ISBN: 0820305138

Janet Beer, Edith Wharton (Writers & Their Work), New York: Northcote House, 2001, pp.99, ISBN: 0746308981

Millicent Bell (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Edith Wharton, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp.232, ISBN: 0521485134

Alfred Bendixen and Annette Zilversmit (eds), Edith Wharton: New Critical Essays, New York: Garland, 1992, pp.329, ISBN: 0824078489

Eleanor Dwight, Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, ISBN: 0810927950

Gloria C. Erlich, The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton, California: University of California Press, 1992, pp.223, ISBN: 0520075838

Susan Goodman, Edith Wharton’s Women: Friends and Rivals, UPNE, 1990, pp.220, ISBN: 0874515246

Irving Howe, (ed), Edith Wharton: A collection of Critical Essays, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1986,

Jennie A. Kassanoff, Edith Wharton and the Politics of Race, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp.240, ISBN: 0521830893

Hermione Lee, Edith Wharton, London: Vintage, new edition 2008, pp.864, ISBN: 0099763516

R.W.B. Lewis, Edith Wharton: A Biography, New York: Harper and Rowe, 1975, pp.592, ISBN: 0880640200

James W. Tuttleton (ed), Edith Wharton: The Contemporary Reviews, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp.586, ISBN: 0521383196

Candace Waid, Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991,

Sarah Bird Wright, Edith Wharton A to Z: The Essential Reference to Her Life and Work, Fact on File, 1998, pp.352, ISBN: 0816034818

Cynthia Griffin Wolff, A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton, New York: Perseus Books, second edition 1994, pp.512, ISBN: 0201409186

Other works by Edith Wharton

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Reef deals with three topics with which Edith Wharton herself was intimately acquainted at the period of its composition – unhappy marriage, divorce, and the discovery of sensual pleasures. The setting is a country chateau in France where diplomat George Darrow has arrived from America, hoping to marry the beautiful widow Anna Leith. But a young woman employed as governess to Anna’s daughter proves to be someone he met briefly in the past and has fallen in love with him. She also becomes engaged to Anna’s stepson. The result is a quadrangle of tensions and suspicions about who knows what about whom. And the outcome is not what you might imagine.

The Reef deals with three topics with which Edith Wharton herself was intimately acquainted at the period of its composition – unhappy marriage, divorce, and the discovery of sensual pleasures. The setting is a country chateau in France where diplomat George Darrow has arrived from America, hoping to marry the beautiful widow Anna Leith. But a young woman employed as governess to Anna’s daughter proves to be someone he met briefly in the past and has fallen in love with him. She also becomes engaged to Anna’s stepson. The result is a quadrangle of tensions and suspicions about who knows what about whom. And the outcome is not what you might imagine.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Edith Wharton – web links

![]() Edith Wharton at Mantex

Edith Wharton at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, tutorials on the shorter fiction, bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

![]() Edith Wharton at Gutenberg

Edith Wharton at Gutenberg

Free eTexts of the major novels and collections of stories in a variety of digital formats – also includes travel writing and interior design.

![]() Edith Wharton at Wikipedia

Edith Wharton at Wikipedia

Full details of novels, stories, and travel writing, adaptations for television and the cinema, plus web links to related sites.

![]() The Edith Wharton Society

The Edith Wharton Society

Old but comprehensive collection of free eTexts of the major novels, stories, and travel writing, linking archives at University of Virginia and Washington State University.

![]() The Mount: Edith Wharton’s Home

The Mount: Edith Wharton’s Home

Aggressively commercial site devoted to exploiting The Mount – the house and estate designed by Edith Wharton. Plan your wedding reception here.

![]() Edith Wharton at Fantastic Fiction

Edith Wharton at Fantastic Fiction

A compilation which purports to be a complete bibliography, arranged as novels, collections, non-fiction, anthologies, short stories, letters, and commentaries – but is largely links to book-selling sites, which however contain some hidden gems.

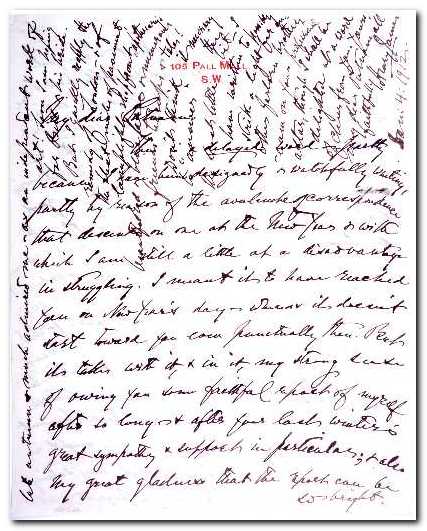

![]() Edith Wharton’s manuscripts

Edith Wharton’s manuscripts

Archive of Wharton holdings at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© Roy Johnson 2011

More on Edith Wharton

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

Ethan Frome

Ethan Frome