Jazz criticism from a major English poet

Larkin’s Jazz is a collection of record and book reviews that has been assembled to flesh out Philip Larkin’s oeuvre of writings on jazz. It also seeks to correct the idea that he was a jazz reactionary — an impression he created himself by his introduction to All What Jazz, the collection of his monthly record reviews for The Daily Telegraph. This also covers a wider time span – starting with a piece he wrote for a school magazine and going up into the early 1980s.

It’s a collection of reviews from the Guardan the Observer and elsewhere. What emerges is a rational, humane view of jazz and related topics, a sincere concern for the plight of African-Americans (who he refers to as Negroes – which was PC at the time) and of course a lustful sense of fun for the music. He writes on Count Basie, Billy Holiday, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, jazz photography, other jazz critics such as Francis Newton and LeRoi Jones. The editors Richard Palmer and John White do everything they can to reclaim the image of Larkin which has been generated by his biographies and published correspondence:

It’s a collection of reviews from the Guardan the Observer and elsewhere. What emerges is a rational, humane view of jazz and related topics, a sincere concern for the plight of African-Americans (who he refers to as Negroes – which was PC at the time) and of course a lustful sense of fun for the music. He writes on Count Basie, Billy Holiday, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, jazz photography, other jazz critics such as Francis Newton and LeRoi Jones. The editors Richard Palmer and John White do everything they can to reclaim the image of Larkin which has been generated by his biographies and published correspondence:

these book reviews give the lie to the charges of misogynist, racist and anti-modernist curmudgeon levelled against Larkin by politically correct critics who also revealed themselves as incapable of detecting irony or wit in the purple prose that vivifies much of his correspondence.

Whether they do that or not depends partly on how much else any reader already knows about Larkin and his – ahem, idiosyncratic views and tastes. But these pieces are certainly well worth reading in their own right. As a reviewer myself, I noticed how well-crafted the reviews are – amazingly short, yet combining an account of the book or the record, a personal opinion, and a neat sliver of readable journalism as well.

Of course much of what he has to say is about very traditional forms of jazz, and even though that’s clearly his own taste it’s not entirely his own fault. He was reviewing at a time when most print publications on the subject of jazz were rather conservative.

He admires the writing of Whitney Balliett, but sees its limitations:

in the end we are left with the impression of brilliant superficiality. Perhaps that is editorial policy: the New Yorker was always strong on polish. But the only thing you can polish is a surface.

This collection has been edited with loving care. Even the smallest items and least-known names are swaddled in supportive endnotes. It’s one for connoisseurs: devotees of jazz music, or those interested in the opinions and occasional writings of a very influential poet.

© Roy Johnson 2002

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Richard Palmer and John White (eds) Larkin’s Jazz: Essays and Reviews 1940-84, London: Continuum, 2001, pp.190, ISBN: 0826453465

More on music

More on media

More on lifestyle

In the magazine and on his blog at

In the magazine and on his blog at

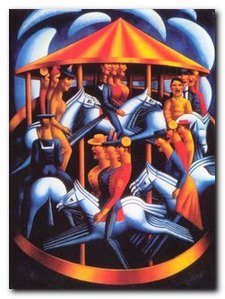

Mark Gertler (1896—1939) was born in Spitalfields in London’s East End, the youngest son of Jewish immigrant parents. When he was a year old, the family was forced by extreme poverty back to their native Galicia (Poland). His father travelled to America in search of work, but when this plan failed the family returned to London in 1896. As a boy he showed a marked talent for drawing, and on leaving school in 1906 he enrolled in art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic, which was the first institution in the UK to provide post-school education for working people.

Mark Gertler (1896—1939) was born in Spitalfields in London’s East End, the youngest son of Jewish immigrant parents. When he was a year old, the family was forced by extreme poverty back to their native Galicia (Poland). His father travelled to America in search of work, but when this plan failed the family returned to London in 1896. As a boy he showed a marked talent for drawing, and on leaving school in 1906 he enrolled in art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic, which was the first institution in the UK to provide post-school education for working people. In 1914 he was also taken up by Edward Marsh an art collector who was later to become secretary to Winston Churchill. Even this relationship became difficult, since Gertler was a pacifist, and he disapproved of the system of patronage. He broke off the relationship, and around this time painted what has become his most famous painting – The Merry-Go-Round.

In 1914 he was also taken up by Edward Marsh an art collector who was later to become secretary to Winston Churchill. Even this relationship became difficult, since Gertler was a pacifist, and he disapproved of the system of patronage. He broke off the relationship, and around this time painted what has become his most famous painting – The Merry-Go-Round.