find bargains at online bookshops

find bargains at online bookshops

I’ve bought several books for a penny each in the last couple of weeks at Amazon. Yes – that’s one penny. And they were not tatty old paperbacks, but hardback reference works of 400 pages plus, in tip top condition, plus a couple of classic novels.

There are several factors that create this state of affairs:

- new books drive down the value of old books

- book sales are dropping in global terms

- more people are buying eBooks

- eCommerce is changing business practices

What type of books for a penny?

There are lots of junk books for a penny available – as you would expect. But there are just as many that have real intrinsic value in the hands of the right person:

- dictionaries

- reference books

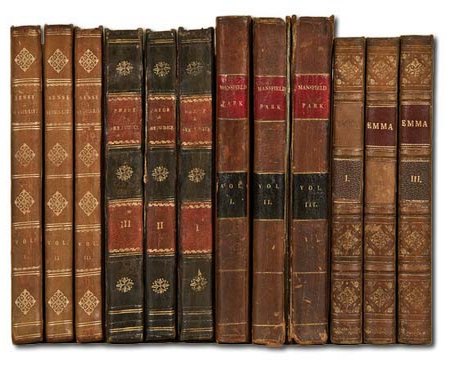

- classic novels

- out of date text books

- software and IT manuals

A copy of the classic reference book Whitaker’s Almanack for instance contains lots of valuable information, even if it’s a few years out of date.

You can bet that the capital city, the geography, and the principal imports and exports of Tasmania have not changed much in the last two or three years.

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice hasn’t changed at all since it was first published nearly two hundred years ago. So you can safely buy a copy that happens to be fifty years old – especially if it’s a nice hardback edition, printed on good paper.

Say you were a student of mathematics. A textbook explaining algebra, geometry, or calculus can’t really be ‘out of date’ – because the rules and equations in maths are fixed as part of their very nature.

In the world of computer technology, developments are so rapid that both software and hardware are updated every few weeks. A guidance manual to a digital camera, an operating system, or a laptop computer has almost zero value after about twelve months. But it might be useful to you if it matches the age of your equipment.

Why do books for a penny exist?

Theese bargain books are available for two good reasons:

Reason one

The bookseller wants to get rid of books that aren’t selling and are taking up valuable storage space.

This makes room for books that are more popular and will make more money in terms of sales.

Reason two

The bookseller is getting valuable information in return for the sale – your name, postal address, email address, and your reading preferences.

The bookseller can make use of this information in any future marketing campaigns.

Hardback Vs paperback

Check the book descriptions carefully. You might find a hardback edition available for the same price as a paperback. Old paperbacks tend to disintegrate, and a hardback edition will be more durable, even if it is much older

A hardback might also have additional features – such as illustrations, photographs, and maps.

How to interpret descriptions

Here is a typical description from a bookseller’s advert – and on some sites you might get a photograph of the book as well.

Ex-Library Book. Has usual library markings and stamps inside. Has been read but remains in clean condition. All pages are intact and the cover is intact. The spine may show signs of wear. All orders are dispatched within 1 working day from our UK warehouse. Established in 2004, we are dedicated to recycling unwanted books on behalf of a number of UK charities who benefit from added revenue through the sale of their books plus huge savings in waste disposal. No quibble refund if not completely satisfied.

- Ex-Library book – That’s OK: libraries often laminate their books, to make them more durable. The book might have tickets and coloured stamp markings inside.

- Pages and cover inteact – Good. That means it’s in reasonable external condition.

- Spine wear – That is perfectly normal on an old book.

- Despatched within one day – Good! Order it in the morning: you might receive it next day.

- Charity donation – You are helping a charity, and saving a book which would otherwise be pulped.

- Money-back guarrantee – You can trust them to honour their promise – for reasons discussed below.

If you want to go into further detail, have a look at our guidance notes on bookseller jargon.

Can you trust the seller?

Almost all bookseller want to gain reputations for good service and prompt delivery. Amazon and AbeBooks have ratings systems in place. Customers can award good (or bad) marks to the online bookseller.

Believe me – these booksellers are very, very keen to keep their ratings as high as possible. They know that if they send you shoddy goods that are badly wrapped, they will lose credibility,

Postage

Of course, you’ve got to pay the postage for these books to be delivered to your front door. But with an average charge of £2.50 (or $4.00 – €3.00) ask yourself if it would cost you that much to travel to your nearest big bookshop.

You might have to wait two or three days (in the UK) for the book to arrive – but in some cases if you order early in the morning, it’s possible that the book could arrive next day.

However, some online booksellers have free delivery options.

Examples of books for a penny

I ran a test and came up with the following examples. All were available for one penny.

These are the original book reviews on this site. Click through to Amazon, When you get there, be prepared to do a bit of clicking around.

![]() Roget’s Thesaurus [Reference – hardback]

Roget’s Thesaurus [Reference – hardback]

![]() Portrait of a Marriage [Biography – hardback]

Portrait of a Marriage [Biography – hardback]

![]() Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable [Reference – hardback]

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable [Reference – hardback]

![]() iPhone UK The Missing Manual [Guidance manual – paperback]

iPhone UK The Missing Manual [Guidance manual – paperback]

![]() Style: ten lessons in clarity and grace [Style guide – paperback]

Style: ten lessons in clarity and grace [Style guide – paperback]

© Roy Johnson 2013

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

At the end of any scholarly writing (an essay, report, or dissertation) you should offer a list of any works you have consulted or from which you have quoted. This list is called a bibliography – literally, a list of books or sources.

At the end of any scholarly writing (an essay, report, or dissertation) you should offer a list of any works you have consulted or from which you have quoted. This list is called a bibliography – literally, a list of books or sources.

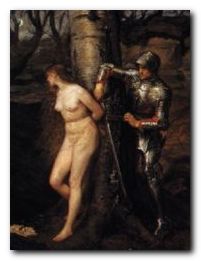

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.

1. In preparation for writing a piece of work, you should take notes from a number of different sources: course materials, set texts, secondary reading, interviews, or tutorials and lectures. You might gather information from radio or television broadcasts, or from experiments and research projects. The notes could also include your own ideas, generated as part of the planning process.

1. In preparation for writing a piece of work, you should take notes from a number of different sources: course materials, set texts, secondary reading, interviews, or tutorials and lectures. You might gather information from radio or television broadcasts, or from experiments and research projects. The notes could also include your own ideas, generated as part of the planning process.