tutorial, study guide, plot summary, study resources

The Illustrious Gaudissart (1833) features a character who will crop up in a number of Balzac’s later novels – Scenes from the Life of a Courtesan (1838-1846), Cesar Birotteau (1837), and Cousin Pons (1846-1847). Gaudissart goes on later to become the owner of a theatre, but is here put forward as the epitome of the travelling salesman.

The Illustrious Gaudissart – commentary

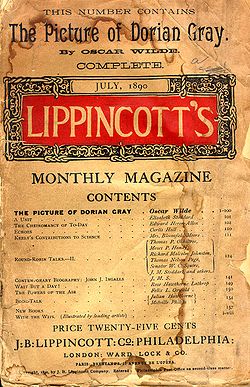

The story offers a wonderful example of Balzac as a satirical, ironic sociologist. He astutely identifies a new social type and pours mockery onto him as a vulgar parvenu, a man who (to quote Oscar Wilde) ‘knows

the price of everything and the value of nothing’.

The first part of the story is a detailed analysis of everything Balzac sees as meretricious and shoddy in this ‘hail fellow, well met’ type with his jokes, his sales patter, and his lack of social or ethical depth.

Balzac was a staunch conservative, royalist, and Catholic. He sees this new style of seedy entrepreneur as an example of the declining civic values following the revolution. Yet Balzac was himself an ambitious and hard-working provincial – with social aspirations. He cannot but partly admire Gaudissart’s persistence and enterprise – peddling newspaper subscriptions and life insurance policies, plus selling hats and the ‘article Paris‘ at the same time.

He takes from the luminous centre a handful of light, and scatters it broadcast among the drowsy populations of the duller regions. This human pyrotechnic is a scholar without learning, a juggler hoaxed by himself, an unbelieving priest of mysteries and dogmas, which he expounds the better for his want of faith. Curious being! He has seen everything, known everything, and is up in all the ways of the world.

The story is essentially an episode in which this vain, boastful, and over-confident con man is duped by wily provincials. The narrative peters out with a rather farcical conclusion, but leaves behind an interesting study in ‘enterprise’ which sits comfortably within the grand scheme of La Comedie Humaine.

Gaudissart II

In a later story by this title, published in 1846, the name Gaudissart is used as a generic term to describe all cunning salesmen. The story centres on a fashionable Parisian store in which the manager sells an Englishwoman an expensive shawl. He does so by a mixture of subtle sales techniques, psychological insight, flattery, and boastfulness mixed with a dash of sharp practice. Balzac sees this example of ‘Gaudissart’ as a social force.

The Illustrious Gaudissart – study resources

The Human Comedy – NYRB Classics – Amazon UK

The Human Comedy – NYRB Classics – Amazon US

Cousin Pons – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Cousin Pons – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

All characters in La Comedie Humaine

Cambridge Companion to Balzac – Cambridge UP – Amazon UK

The Illustrious Gaudissart – plot summary

Ch.I The commercial traveller as a new social type. He moves between the city and the provinces but belongs to neither. His task is to extract commissions by persuasion. Gaudissart is a successful example who is living in Paris in semi-retirement – all things to all men. He is approached to sell life insurance, and thinks to promote newspaper subscriptions at the same time – to both a Monarchist and a republican publication.

Ch.II Gaudissart promises to bring home wealth to his mistress Jenny Courand. He also plans to sell subscriptions to a children’s newspaper – and he nurtures secret political ambitions. He writes Jenny a letter from the provinces, boasting of his commercial success.

Ch.III He arrives in Tours, a city which prides itself on hard-headed realism. When Gaudissart tries his vague salesmanship on M. Vernier, the Tourangian as a joke steers him towards Margaritis, the local lunatic, pretending that he is a banker.

Ch.IV Gaudissart tries to sell life insurance to Margaritis, who in his turn tries to sell wine (which he doesn’t have) to Gaudissart. In the end Gaudissart buys the wine, and Margaritis buys subscriptions to the children’s newspaper.

Ch.V Gaudissart discovers that he has been duped and complains to Vernier. The two men quarrel and a duel is arranged. It turns out to be a farce, with Vernier shooting a cow in a nearby field. They call a truce, and Vernier takes out twenty subscriptions to the children’s newspaper. Gaudissart later brags about killing a man in a duel.

The Illustrious Gaudissart – characters

| Felix Gaudissart | a 38 year old boastful travelling salesman |

| Jenny Courand | Gaudissart’s mistress in Paris, a florist |

| Vernier | a retired dyer in Tours |

| Margaritis | a lunatic in Tours who thinks he owns vineyards |

© Roy Johnson 2018

More on Honore de Balzac

More on literary studies

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles Jude the Obscure

Jude the Obscure Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

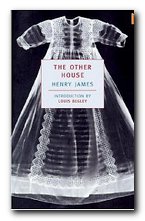

The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All essays are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work.

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All essays are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel – the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian father. She has a handsome young suitor – but her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant town house. Who wins out in the end? You will be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, with a sensitive picture of a woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel – the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian father. She has a handsome young suitor – but her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant town house. Who wins out in the end? You will be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, with a sensitive picture of a woman’s life.  The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.