tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

A London Life first appeared in Scribner’s Magazine, vols 3—4 (June—September 1888). It is one of the longest of James’s tales – in fact it belongs in the category he particularly admired which we now call the nouvelle or novella. In subject matter it is fairly close to What Masie Knew (1897) and The Awkward Age (1899) in dealing with the issue of problematic marriages and their effect on children, relatives, and friends.

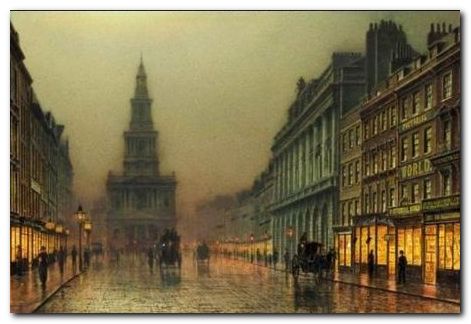

The Strand – John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836-1893)

A London Life – critical commentary

This is a curiously uneven piece of work by James’s usual standards, marred by what seem like a fractured spine and an absence of resolution. The first half of the novella, set on the Berrington estate at Mellows, is leisurely and establishes the triangulation of the family conflict quite evenly. Laura is the protagonist and the focaliser of events, whilst her sister and brother-in-law provide the dramatic conundrum, and Lady Davenant is like the Greek chorus, offering Laura humane wisdom as she faces her personal dilemma.

At the end of this period there is a lull in the drama when Lionel and Selina cease feuding and get on better together. Laura even reconciles herself to accepting the state of affairs. This is credible enough in terms of a realistic account of the ebb and flow of human relationships, but it doesn’t seem to serve any dramatic purpose, because there is not going to be any harmonising resolution in the plot.

In the second part of the tale, when the scene moves to London, there is a distinct shift in tone. A new character is introduced – Mr Wendover – who provides the romantic interest for Laura. But he proves to be an odd mixture. He declares his love to Laura, tells Lady Davenant he is leaving London, and then pursues Laura to America.

Laura’s climactic scene at the opera has all the hallmarks of a passage in which her hyperventilating view of events suggests that she might have an unreliable understanding of what is going on around her. There is no evidence in the text that her interpretation of events is sound – yet it proves to be the case that Selina does use the occasion to elope with Captain Crispin.

We are given no further account of events from Selina’s point of view, only her husband’s outrage and desire to pursue the divorce. Therefore the only dramatic point of interest remains with Laura – who decides to follow her sister with some vague idea of bringing her back.

She follows her to Brussels, but we do not learn what happens there, and can only conclude that the pursuit was fruitless, since Laura then goes back to America, pursued herself by Mr Wendover. There is therefore no satisfactory dramatic resolution to the strands of the plot that James establishes in the earlier parts of the story. All we know is that the divorce case has reached the courts.

Marriage, money, and inheritance

The story reveals some interesting details about social conventions amongst the English and American upper-classes in the late nineteenth century. Under the ‘laws’ (conventions) of primogeniture Lionel Berrington has inherited the family estate at Mellows on the death of his father. This inheritance even takes precedence over his own mother, who has been moved out of the family home and settled in a separate dower house on the estate at Plash.

Laura’s family have paid money to the Berrington family in the form of a dowry on the marriage of their eldest daughter Selina to Lionel. This has two important social consequences. First – it means there is no money left for Laura, so she is living on the charity of her sister and brother in law. This leaves her both socially and existentially anxious – because she has no independence and no social status unless she herself marries.

Moreover, if there is a scandal between Lionel and Selina (as proves to be the case) this will attach a negative social reputation to the Berrington family, which will make Laura’s chances of finding a suitable husband even more difficult.

On top of this, in the divorce court case of ‘Berrington Vs Berrington and others’, if Selina is found guilty (as seems likely) she will lose her social status and more importantly the capital invested in her marriage. Thus Laura’s future prospects will be undermined even further.

The novella

Any claims that this is a successful example of the novella form must stand up against the observation that it lacks unity of theme, location, or any consistency of preoccupation. Even the title of the story seems eccentric, since the first half of the narrative is located at a country estate, and none of the drama is essentially related to the capital.

Certainly the second half of the story is located in London – but both Laura Wing and Mr Wendover are Americans, and they are not affected by anything to do with London, so much as the bad behaviour of Selina and her husband, who could be living anywhere.

The ending of the story also leaves many of its elements unresolved. We do not know what happened when Laura reached Brussels, but can only infer that her mission to retrieve Selina was unsuccessful. We do not know what she will do back in America, or what becomes of her. We do not know if Mr Wendover’s on-off pursuit of Laura will be successful or not. These are loose ends – not the tight construction of a successful novella.

A London Life – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() A London Life – Classic Reprint edition

A London Life – Classic Reprint edition

![]() A London Life – World’s Classics edition

A London Life – World’s Classics edition

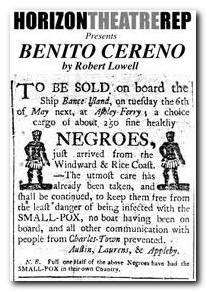

![]() A London Life – the original magazine publication

A London Life – the original magazine publication

![]() A London Life – eBook formats at Gutenberg

A London Life – eBook formats at Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

A London Life – plot summary

Part I. A young American woman Laura Wing discusses the issue of her ‘poverty’ and prospects in life with her older English friend Lady Davenant. The money in Laura’s family has gone to her elder sister Selina, with whom Laura is now living in England on a charitable basis. Selina is married to Lionel Berrington, who has inherited the Mellows estate following his father’s death. Lionel’s mother Mrs Berrington has been moved to live in a dower house at Plash, on the estate. Laura senses problems in her sister’s marriage, since the couple spend almost no time together, and she fears that her sister might create a scandal. She also feels insecure about her own lack of social status or any meaningful purpose in life.

Part II. The Berrington children are neglected by both parents, and Laura feels sympathetically drawn to Miss Steet, their governess, even though her sister snobbishly disapproves of social contacts with the family’s employees. Lionel returns unexpectedly from one of his absences to report that Selina has been seen in Paris with a friend Lady Ringrose, of whom he disapproves. He has clearly been drinking, and both Miss Steet and Laura are embarrassed by his vulgar behaviour and the unsavoury details of the family conflict he is revealing.

Part III. Lionel reappears once again later to reveal that Selina is in fact in Paris with her latest lover Captain Crispin, and that he intends to divorce her. He wants Laura’s help, but she is appalled and distressed by the idea of a scandal in the family.

Part IV. When Selina returns from Paris Lionel challenges her with this information. There is savage conflict between them, but to Laura she completely denies being with Captain Crispin, and in retaliation defames her husband’s own character.

Part V. Following this however Lionel and Selina appear to return to a tolerant attitude towards each other, which leaves Laura feeling apprehensive. She thinks of escaping, but learns to live in the morally ambiguous atmosphere which prevails at Mellows.

Part VI. When the Berrington family return from the country to lives in their various London homes for the ‘season’ Laura meets Mr Wendover, a fellow American who appeals to her because his open and forthright manner reminds her of ‘home’. He is naively eager to absorb the best of English society and manners, so Laura takes him to meet her friend Lady Davenant, where they all get on well together.

Part VII. Laura and Wendover explore London together, and she begins to reflect meanwhile more charitably on her sister’s possible innocence – since Selina is spending time with a friend in need in Weybridge. But whilst they are in the Soane Museum they bump into Selina in the company of Captain Crispin – which plunges Laura into renewed consternation.

Part VIII. Laura debates with herself the possible explanations for her sister’s socially reckless behaviour, but when they go out to dinner it is Selina who reproaches Laura for breaking the rules of social etiquette. She points out that it is not acceptable for a single woman to go sightseeing on her own with a bachelor.

Part IX. Laura contemplates revealing to Lionel that she has seen Selina with the man he suspects to be her lover. She sits up late into the night, waiting for her sister to come home. When Selina finally arrives, she bursts into tears and appeals to Laura to remain and help to ‘save’ her, promising never to see Captain Crispin again.

Part X. Laura subsequently forms a closer bond with her sister, and takes her out to concerts and galleries. She reports all this to her friend Lady Daventry, who still encourages Laura to take an interest in Mr Wendover. When Laura and her sister accept an invitation from Mr Wendover to his box at the opera, Selina goes to join Lady Ringrose in another box and doesn’t return. Laura suddenly feels exposed and betrayed again. She feels sure Selina is secretly meeting Captain Crispin, and even though Mr Wendover declares that he loves her, she doubts his sincerity.

Part X. Laura subsequently forms a closer bond with her sister, and takes her out to concerts and galleries. She reports all this to her friend Lady Daventry, who still encourages Laura to take an interest in Mr Wendover. When Laura and her sister accept an invitation from Mr Wendover to his box at the opera, Selina goes to join Lady Ringrose in another box and doesn’t return. Laura suddenly feels exposed and betrayed again. She feels sure Selina is secretly meeting Captain Crispin, and even though Mr Wendover declares that he loves her, she doubts his sincerity.

Part XI. Selina disappears, leaving Laura to appeal to Lady Davenant for help. Her friend takes her in and sends for Mr Wendover, who reveals that he has no money and no intention of marrying Laura. He says that he is shortly due to leave London

Part XII. Laura is ill for a few days. Lionel visits her but refuses to reveal her sister’s whereabouts, because he wishes to recruit Laura to his own cause in divorce proceedings. Mr Wendover comes back again – but Laura rejects him and extracts from Lionel the fact that Selina has gone to Brussels.

Part XIII. Laura follows her sister to Brussels, and from there travels on to America, where Mr Wendover follows her, as the divorce case of ‘Berrington Vs Berrington and others’ gets under way in London.

Principal characters

| Laura Wing | a young American woman living in England |

| Selina Berrington | Laura’s elder sister |

| Mrs Berrington | a widow living in a dower house |

| Lionel Berrington | her son, who has inherited the Mellows estate |

| Lady Davenant | a friend of Mrs Berrington and confidante to Laura |

| Miss Steet | governess to the Berrington children |

| Scratch/Geordie | son of Berringtons |

| Parson/Ferdy | son of Berringtons |

| Lady Ringrose | friend of Selina’s |

| Captain Charley Crispin | Selina’s lover |

| Lord Deepmere | a previous lover of Selina’s |

| Mr Wendover | an American bachelor |

| Mr Booke | his opera-loving friend |

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2013

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

William (Billy) Budd is a handsome and popular young sailor, serving on a merchant ship The Rights of Man. He a great favourite of his ship’s master, Captain Graveling. In 1897 however, Billy is impressed into service on the HMS Bellipotent which is commanded by the aristocratic Edward Fairfax (‘Starry’) Vere. Billy is a figure of innocence and good nature. He is an illiterate foundling (an abandoned and presumably illegitimate child) and is popular with other crew members. But the ship’s master-at-arms John Claggart is fuelled by a malevolent impulse to harm Billy. He reports him to the captain, falsely accusing him of fomenting a mutiny.

William (Billy) Budd is a handsome and popular young sailor, serving on a merchant ship The Rights of Man. He a great favourite of his ship’s master, Captain Graveling. In 1897 however, Billy is impressed into service on the HMS Bellipotent which is commanded by the aristocratic Edward Fairfax (‘Starry’) Vere. Billy is a figure of innocence and good nature. He is an illiterate foundling (an abandoned and presumably illegitimate child) and is popular with other crew members. But the ship’s master-at-arms John Claggart is fuelled by a malevolent impulse to harm Billy. He reports him to the captain, falsely accusing him of fomenting a mutiny.

Gustav von Aschenbach is a famous author in his early fifties. He is a widower, dedicated to his art, and disciplined to the point of severity. While strolling outside a cemetery in his native Munich he has a disturbing encounter with a red-haired man, after which he resolves to take a trip. He reserves a suite in the Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Lido island of Venice. While en route to the island by vaporetto, he sees an elderly man with a wig, false teeth, makeup, and foppish attire, which disgusts him. Soon afterwards he has a disturbing encounter with a gondolier.

Gustav von Aschenbach is a famous author in his early fifties. He is a widower, dedicated to his art, and disciplined to the point of severity. While strolling outside a cemetery in his native Munich he has a disturbing encounter with a red-haired man, after which he resolves to take a trip. He reserves a suite in the Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Lido island of Venice. While en route to the island by vaporetto, he sees an elderly man with a wig, false teeth, makeup, and foppish attire, which disgusts him. Soon afterwards he has a disturbing encounter with a gondolier.

Thomas Mann: a life This exploration of Thomas Mann’s life by Donald Prater describes his relationship of intense rivalry with his brother Heinrich, who was also a novelist, his (much-concealed) homosexuality, his career as a prolific essayist, and the vast achievement of his novels. Particular attention is paid to Mann’s opposition to Nazism, and his role in the rise and fall of Hitlerism. It traces Mann’s political development from the nationalistic conservatism of his younger days, to the humanistic anti-Nazim of his maturity.

Thomas Mann: a life This exploration of Thomas Mann’s life by Donald Prater describes his relationship of intense rivalry with his brother Heinrich, who was also a novelist, his (much-concealed) homosexuality, his career as a prolific essayist, and the vast achievement of his novels. Particular attention is paid to Mann’s opposition to Nazism, and his role in the rise and fall of Hitlerism. It traces Mann’s political development from the nationalistic conservatism of his younger days, to the humanistic anti-Nazim of his maturity.  Mario and the Magician

Mario and the Magician The Magic Mountain

The Magic Mountain

Ethan Frome is a poor working farmer who lives in a small remote town in Massachusetts. He exists in a state of near poverty with his wife Zeena (Zenobia), a grim, prematurely aged woman who makes hypochondria her hobby and his life a misery. Ethan has travelled as far as Florida and has intellectual aspirations, but he has never been able to develop or fulfil them. Living with them as an unpaid household help is Zeena’s cousin, Mattie Silver, a young woman who has lost her parents.

Ethan Frome is a poor working farmer who lives in a small remote town in Massachusetts. He exists in a state of near poverty with his wife Zeena (Zenobia), a grim, prematurely aged woman who makes hypochondria her hobby and his life a misery. Ethan has travelled as far as Florida and has intellectual aspirations, but he has never been able to develop or fulfil them. Living with them as an unpaid household help is Zeena’s cousin, Mattie Silver, a young woman who has lost her parents.

The Age of Innocence

The Age of Innocence The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Nostromo

Nostromo The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent