tutorial, characters, resources, videos, writing

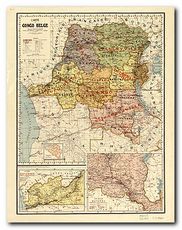

Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of the process of Imperialism. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement, and it is based on his own experiences as a sea captain.

Joseph Conrad

Heart of Darkness – plot summary

The story opens with five men on a boat on the river Thames. Marlow begins telling a story of a job he took as captain of a steamship in Africa. He begins by ruminating on how Britain’s image among Ancient Roman officials must have been similar to Africa’s image among nineteenth century British officials. He describes how his aunt secured the job for him. When he arrives in Africa, he encounters many men he dislikes as they strike him as untrustworthy. They speak of a man named Kurtz, who has a reputation as a rogue ivory collector, but who is “essentially a great musician,” a journalist, a skilled painter and “a universal genius.”

Marlow arrives at the Central Station run by the general manager, an unwholesome conspiratorial character. He finds that his steamship has been sunk and spends several months waiting for parts to repair it. Kurtz is rumored to be ill, making the delays in repairing the ship all the more costly. Marlow eventually gets the parts and he and the manager set out with a few agents and a crew of cannibals on a long, difficult voyage up river. The dense jungle and oppressive silence make everyone aboard a little jumpy and the occasional glimpse of a native village or the sound of drums works the voyagers into a frenzy.

Marlow arrives at the Central Station run by the general manager, an unwholesome conspiratorial character. He finds that his steamship has been sunk and spends several months waiting for parts to repair it. Kurtz is rumored to be ill, making the delays in repairing the ship all the more costly. Marlow eventually gets the parts and he and the manager set out with a few agents and a crew of cannibals on a long, difficult voyage up river. The dense jungle and oppressive silence make everyone aboard a little jumpy and the occasional glimpse of a native village or the sound of drums works the voyagers into a frenzy.

Marlow and his crew come across a hut with stacked firewood together with a note saying that the wood is for them but that they should approach cautiously. Shortly after the steamer has taken on the firewood it is surrounded by a dense fog. When the fog clears, the ship is attacked by an unseen band of natives, who fire arrows from the safety of the forest. A Russian trader who meets them as they come ashore, assures them that everything is fine and informs them that he is the one who left the wood. Kurtz has established himself as a god with the natives and has gone on brutal raids in the surrounding territory in search of ivory.

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

One night Marlow happens upon Kurtz, obviously near death. As Marlow comes closer with a candle, Kurtz seems to experience a moment of clarity and speaks his last words: “The horror! The horror!” Marlow believes this to be Kurtz’s reflection on the events of his life. Marlow does not inform the Manager or any of the other voyagers of Kurtz’s death; the news is instead broken by the Manager’s child-servant.

Marlow later returns to his home city and is confronted by many people seeking things and ideas of Kurtz. Marlow eventually sees Kurtz’s fiancée about a year later; she is still in mourning. She asks Marlow about Kurtz’s death and Marlow informs her that his last words were her name — rather than, as really happened, “The horror! The horror!”

The story’s conclusion returns to the boat on the Thames and mentions how it seems as though the boat is drifting into the heart of the darkness.

Study resources

![]() Heart of Darkness – Oxford University Press – Amazon UK

Heart of Darkness – Oxford University Press – Amazon UK

![]() Heart of Darkness – Oxford University Press – Amazon US

Heart of Darkness – Oxford University Press – Amazon US

![]() Heart of Darkness – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Heart of Darkness – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Heart of Darkness – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Heart of Darkness – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Heart of Darkness – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

Heart of Darkness – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Heart of Darkness – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

Heart of Darkness – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() Heart of Darkness – eBook version at Project Gutenberg – [FREE]

Heart of Darkness – eBook version at Project Gutenberg – [FREE]

![]() Heart of Darkness – York Notes (Advanced) – Amazon UK

Heart of Darkness – York Notes (Advanced) – Amazon UK

![]() Heart of Darkness – audioBook version (unabridged) – Amazon UK

Heart of Darkness – audioBook version (unabridged) – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: A Casebook – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: A Casebook – Amazon UK

![]() Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Bloomsbury) – Amazon UK

Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Bloomsbury) – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Chelsea) – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Chelsea) – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad: ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Icon) – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad: ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Icon) – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Routledge) – Amz UK

Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Routledge) – Amz UK

![]() Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Penguin) – Amazon UK

Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ – criticism (Penguin) – Amazon UK

![]() An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’

An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’

![]() Heart of Darkness – audioBook at LibriVox

Heart of Darkness – audioBook at LibriVox

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Joseph Conrad at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Joseph Conrad at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Heart of Darkness – film adaptation

Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of Heart of Darkness transforms events from Europe’s imperialist exploitation of the the Belgian Congo to America’s war in Vietnam in the 1960s. It remains amazingly faithful to the original, even whilst translating the settings and events into the fully mechanised assault of the world’s most powerful industrial nation against a country of poor farmers and peasants. Marlow becomes Captain Willard, who is sent on a mission to terminate (‘with extreme prejudice’) the command of rogue Major Kurtz, who has gone over the border into Cambodia with a band of followers.

Francis Ford Coppola adaptation 1979

![]() See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

Principal characters

| I | an unnamed outer narrator who relays Marlow’s story |

| Marlow | a ferry-boat captain, the principal character and narrator of events |

| Kurtz | chief of the Inner Station of Belgian ivory traders |

| General manager | chief of the Outer Station |

| Chief accountant | impeccably dressed functionary |

| Pilgrims | greedy agents of the Outer Station |

| Cannibals | natives hired as steamer crew |

| Russian trader | a disciple of Kurtz with patched clothes |

| Helmsman | native sailor who is killed in the attack on the boat |

| Kurtz’s African mistress | powerful and mysterious woman who never speaks |

| Kurtz’s ‘intended’ | his devoted fiancee in Bussels |

| Aunt | relative who secures Marlow his job |

Biography

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon US

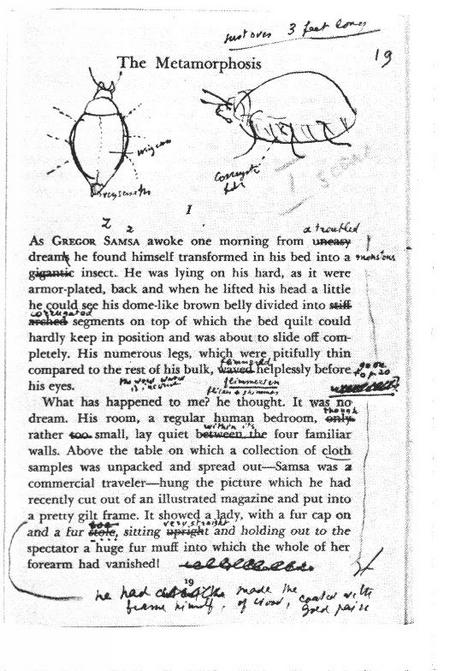

Manuscript page from Heart of Darkness

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon US

Further reading

![]() Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

![]() Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

![]() Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

![]() Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

![]() Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

![]() John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

![]() Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

![]() Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

![]() Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

![]() Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

![]() Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

![]() Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

![]() Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

![]() Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

![]() George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

![]() John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

![]() James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

![]() Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

![]() Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

![]() J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

![]() John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

![]() Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

![]() Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

![]() Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Joseph Conrad’s writing table

Other novels by Joseph Conrad

The Secret Agent (1907) is a short novel and a masterpiece of sustained irony. It is based on the real incident of a bomb attack on the Greenwich Observatory in 1888 and features a cast of wonderfully grotesque characters: Verloc the lazy double agent, Inspector Heat of Scotland Yard, and the Professor – an anarchist who wanders through the novel with bombs strapped round his waist and the detonator in his hand. The English government and police are subject to sustained criticism, and the novel bristles with some wonderfully orchestrated effects of dramatic irony – all set in the murky atmosphere of Victorian London. Here Conrad prefigures all the ambiguities which surround two-faced international relations, duplicitous State realpolitik, and terrorist outrage which still beset us more than a hundred years later.

The Secret Agent (1907) is a short novel and a masterpiece of sustained irony. It is based on the real incident of a bomb attack on the Greenwich Observatory in 1888 and features a cast of wonderfully grotesque characters: Verloc the lazy double agent, Inspector Heat of Scotland Yard, and the Professor – an anarchist who wanders through the novel with bombs strapped round his waist and the detonator in his hand. The English government and police are subject to sustained criticism, and the novel bristles with some wonderfully orchestrated effects of dramatic irony – all set in the murky atmosphere of Victorian London. Here Conrad prefigures all the ambiguities which surround two-faced international relations, duplicitous State realpolitik, and terrorist outrage which still beset us more than a hundred years later.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Under Western Eyes (1911) is the story of Razumov, a reluctant ‘revolutionary’. He is in fact a coward who is mistaken for a radical hero and cannot escape from the existential trap into which this puts him. This is Conrad’s searing critique of Russian ‘revolutionaries’ who put his own Polish family into exile and jeopardy. The ‘Western Eyes’ are those of an Englishman who reads and comments on Razumov’s journal – thereby creating another chance for Conrad to recount the events from a very complex perspective. Razumov achieves partial redemption as a result of his relationship with a good woman, but the ending, with faint echoes of Dostoyevski, is tragic for all concerned.

Under Western Eyes (1911) is the story of Razumov, a reluctant ‘revolutionary’. He is in fact a coward who is mistaken for a radical hero and cannot escape from the existential trap into which this puts him. This is Conrad’s searing critique of Russian ‘revolutionaries’ who put his own Polish family into exile and jeopardy. The ‘Western Eyes’ are those of an Englishman who reads and comments on Razumov’s journal – thereby creating another chance for Conrad to recount the events from a very complex perspective. Razumov achieves partial redemption as a result of his relationship with a good woman, but the ending, with faint echoes of Dostoyevski, is tragic for all concerned.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2010

Joseph Conrad links

![]() Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Biography, tutorials, book reviews, study guides, videos, web links.

![]() Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Brief notes introducing his major works in recommended editions.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary career, style, politics, and further reading.

![]() Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production notes, box office, trivia, and quizzes.

![]() Works by Joseph Conrad

Works by Joseph Conrad

Large online database of free HTML texts, digital scans, and eText versions of novels, stories, and occasional writings.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

Conradian journal, reviews. and scholarly resources.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society of America

The Joseph Conrad Society of America

American-based – recent publications, journal, awards, conferences.

![]() Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Locate a word or phrase – in the context of the novel or story.

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

More on Joseph Conrad tales

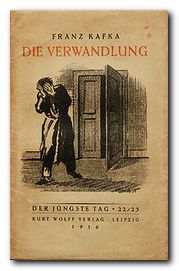

When Gregor’s supervisor arrives at the house and demands Gregor come out of his room, Gregor manages to roll out of bed and unlock his door. His appearance horrifies his family and supervisor; his supervisor flees while his family chases him back into his room.

When Gregor’s supervisor arrives at the house and demands Gregor come out of his room, Gregor manages to roll out of bed and unlock his door. His appearance horrifies his family and supervisor; his supervisor flees while his family chases him back into his room. Later, his parents take in lodgers and use Gregor’s room as a dumping area for unwanted objects. Gregor becomes dirty, covered in dust and old bits of rotten food. One day, Gregor hears Grete playing her violin to entertain the lodgers. Gregor is attracted to the music, and slowly walks into the dining room despite himself, entertaining a fantasy of getting his beloved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. The lodgers see him and give notice, refusing to pay the rent they owe, even threatening to sue the family for harboring him while they stayed there. Grete determines that the monstrous vermin is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. She suggests that they must get rid of it. Gregor retreats to his room and collapses, finally succumbing to his wound, and dying alone.

Later, his parents take in lodgers and use Gregor’s room as a dumping area for unwanted objects. Gregor becomes dirty, covered in dust and old bits of rotten food. One day, Gregor hears Grete playing her violin to entertain the lodgers. Gregor is attracted to the music, and slowly walks into the dining room despite himself, entertaining a fantasy of getting his beloved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. The lodgers see him and give notice, refusing to pay the rent they owe, even threatening to sue the family for harboring him while they stayed there. Grete determines that the monstrous vermin is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. She suggests that they must get rid of it. Gregor retreats to his room and collapses, finally succumbing to his wound, and dying alone. Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

The Trial

The Trial Amerika

Amerika

Herzog (1964) became highly regarded and a classic almost as soon as it was published. It centres intensely on the life of Moses Herzog, a Jewish intellectual who is driven close to the verge of breakdown by the adultery of his second wife with his close friend. He writes letters to famous people, both living and dead – Spinoza, Nietzsche, Winston Churchill, and the President of the USA – giving them a piece of his mind and asking their advice about how to live. The novel begins with a statement which sets the tone for everything that follows: “If I am going out of my mind, it’s all right with me, thought Moses Herzog”.

Herzog (1964) became highly regarded and a classic almost as soon as it was published. It centres intensely on the life of Moses Herzog, a Jewish intellectual who is driven close to the verge of breakdown by the adultery of his second wife with his close friend. He writes letters to famous people, both living and dead – Spinoza, Nietzsche, Winston Churchill, and the President of the USA – giving them a piece of his mind and asking their advice about how to live. The novel begins with a statement which sets the tone for everything that follows: “If I am going out of my mind, it’s all right with me, thought Moses Herzog”. Humboldt’s Gift (1974) traces the life and memories of writer Charlie Citrine as he reflects on the influence of his boyhood friend and mentor, Humboldt. This character is based loosely upon Delmore Schwartz, the Jewish poet and short story writer whose early promise was never fulfilled. He descended into alcoholism and poverty, and died in a cheap hotel room, creating the modern version of the myth of the ‘doomed poet’. The novel deals with the ‘gift’ for aesthetic appreciation he passes on to his close friend Charlie, the narrator of the novel.

Humboldt’s Gift (1974) traces the life and memories of writer Charlie Citrine as he reflects on the influence of his boyhood friend and mentor, Humboldt. This character is based loosely upon Delmore Schwartz, the Jewish poet and short story writer whose early promise was never fulfilled. He descended into alcoholism and poverty, and died in a cheap hotel room, creating the modern version of the myth of the ‘doomed poet’. The novel deals with the ‘gift’ for aesthetic appreciation he passes on to his close friend Charlie, the narrator of the novel. Ravelstein (2000) is something of a double portrait. Abe Ravelstein, a mega-successful Jewish academic realises that he might be dying. He invites his friend Chick to write an biographical study of him. What we get is a not-so-thinly disguised portrait of the critic Allan Bloom written by a character who has had all the brushes with life which Bellow experienced in his own: near-death illness, late-life divorce, and happiness with a new wife.

Ravelstein (2000) is something of a double portrait. Abe Ravelstein, a mega-successful Jewish academic realises that he might be dying. He invites his friend Chick to write an biographical study of him. What we get is a not-so-thinly disguised portrait of the critic Allan Bloom written by a character who has had all the brushes with life which Bellow experienced in his own: near-death illness, late-life divorce, and happiness with a new wife.

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

Washington Square

Washington Square

The Kingdom of This World

The Kingdom of This World The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps