design , modernism, and Russian Suprematism

El Lissitzky (1890-1941) was one of the pioneers of the modernist movement in Russian art which flourished in the period 1915-1925. He was one of the most graphically radical of his era, and yet only a few years earlier he was painting rather conventional landscape paintings in the tradition of Russian realism. El Lissitzky’s earliest creative period was spent at Vitebsk working with Mark Chagall and Kasimir Malevich. With the latter he spearheaded to Suprematist movement. His geometric constructions developed from two to three dimensions and became a sort of theoretical architecture – shapes which float in space. He called the works ‘Proun’ – an invented word which means ‘Project for asserting the New’. El Lissitzky Design is an elegantly illustrated introduction to all this work.

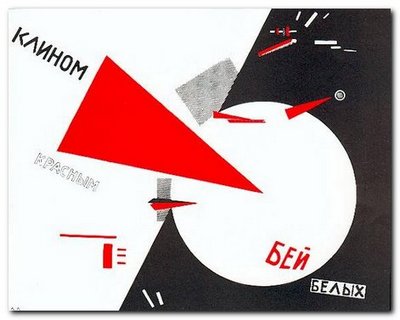

He is best known for his propaganda painting ‘Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge’ of 1919 – a work which very typically for its time was geometric in form, non-representational, and included typographical elements in the same style as his contemporaries Alexander Rodchenko and Malevich. At the same time he also started producing abstract constructions in two and three dimensions which were (like Rodchenko’s) geometrically based, but more mature and developed than any works of this kind that had emerged up to this date.

He is best known for his propaganda painting ‘Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge’ of 1919 – a work which very typically for its time was geometric in form, non-representational, and included typographical elements in the same style as his contemporaries Alexander Rodchenko and Malevich. At the same time he also started producing abstract constructions in two and three dimensions which were (like Rodchenko’s) geometrically based, but more mature and developed than any works of this kind that had emerged up to this date.

His finest work seems to have been produced in an amazing creative outburst between 1917 and 1925 – just at the point where unfettered Russian modernist art theory was taking off alongside the political revolution in its positive and expansive phase.

When El Lissitzky crossed the line between art and work after 1917, he became an international social activist promoting a political message. Like the Russian Constructivists that he admired, he sought to use his creative energy to help design a new social structure in which the new engineer-architect-artist could erase old boundaries.

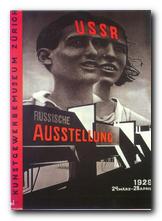

El Lissitzky was fortunate to be at his creative peak at a time when foreign travel was still possible in the USSR. He took exhibitions to Germany and mixed with other modernists such as Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Kurt Schwitters. He had connection with the De Stijl group in Holland, and he taught at the Bahaus.

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.

He lived until 1943, but there is very little that he produced after the mid 1920s that stands up to any degree of scrutiny today. What he produced before then was awe inspiring – and remains so to this day.

© Roy Johnson 2010

John Milner, El Lissitzky – Design, Suffolk: Antique Collectors Club, 2009, pp.96, ISBN: 185149619X

More on art

More on media

More on design

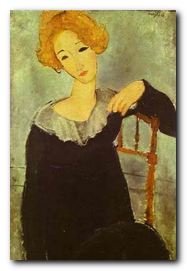

In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and

In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and