tutorial, study guide, resources, and web links

Jude the Obscure (1895) was the last of Thomas Hardy’s novels, and it is generally regarded as expressing his most tragic vision of the world. The novel was subject to extensive censorship on grounds of blasphemy and indecency when it was first published. It was this interference with the creative process that led Hardy to give up writing novels. After this point he concentrated instead on writing poetry, and went on to produce some of the greatest and most influential poems of the twentieth century.

In the novel Hardy explores themes that had interested him throughout his career as a novelist – education, class, sexuality, craftsmanship and tradition, the condition of marriage, and the forces of society and conventions that thwart individual ambition.

Jude the Obscure – a note on the text

The novel had a long and complex genesis. Hardy began its composition in 1890, writing from notes he had made in 1887. He worked on the narrative between 1892 and 1894, and it first saw light of day as a serial story in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine published simultaneously in London and New York.

During this time it had three separate titles – The Simpletons, Hearts Insurgent, and The Recalcitrants before Hardy settled on the final title. However, the text of this early version was heavily bowdlerised, and some of the incidents in the story were significantly different from the story in its final edited version.

The novel first appeared in volume form in 1895, published by Osgood McIlvaine. For this edition Hardy restored some of the missing scenes and put slightly different emphasis on the behaviour and motivation of his characters. It was not until Hardy revised the text for the 1912 edition of the ‘Wessex Edition’ of his novels published by Macmillan that the text became ‘stable’.

For a full account of the history of the text, see Patricia Ingham’s study The Evolution of Jude the Obscure.

Jude the Onscure – critical commentary

Structural parallels

Most readers will have little difficulty spotting the structural elements of the novel that twin and echo each other. Jude Fawley marries Arabella Donn, and lives to regret it. Then Sue Bridehead marries Richard Phillotson, and the result is the same. These parallels constitute the first part of the novel.

Sue and Jude then begin to live together, even though they are not married, but society puts obstacles in their way, because of the prejudice against ‘living in sin’. At this stage both Sue and Jude are both technically still married to other people. Jude is married to Arabella who has gone to Australia, and Sue is married to Phillotson, but has separated from him.

In an attempt to break the prejudice that society has against them, Jude and Sue both secure divorces, but they then live in a state of ambiguity. Many of the other characters they live amongst continue to imagine that they are either adulterous or bigamous. The couple make matters worse for themselves by pretending to get married, but they do not actually go through a formal ceremony. These events constitute the two main central sections of the novel.

Finally, Sue decides she must re-marry Phillotson even though she does not love him and finds him physically repulsive. Then Jude too re-marries Arabella (in a drunken stupor). The outcomes are equally disastrous for both characters. For Sue it is a living death, and for Jude it is death itself. These are the closing chapters of the novel. It is not surprising that many readers find these outcomes unbearably tragic – especially so since Jude’s son murders his brother and sister, then hangs himself.

The sensation novel

In the latter part of the nineteenth century there was a vogue for what was called the ‘sensation novel’. These were novels which featured plot elements of murder, disguise, bigamy, madness, blackmail, fraud, theft, kidnapping, incarceration, or disputed wills. They were a sort of half-way house between the conventional novel of social life and the Gothic horror story which also might include ghosts, vampires, ruined castles, and dead bodies.

Hardy steers clear of the Gothic, but he comes close to the sensation novel in his exploration of personal relationships, sexuality, and the conventions of marriage in Jude the Obscure. All the problems of censorship he endured at the first publication of the novel hinged on infractions of what were considered acceptable topics for polite literature.

At a very minor level, Arabella traps Jude into marriage by pretending to be pregnant after they first start their relationship. In other words, they have had sex before marriage – a phenomenon Hardy had featured in many of his other novels and stories – often citing ‘rural customs’ as justification.

Arabella leaves Jude, goes to Australia, and marries another man. She is therefore committing bigamy – but she argues on return that nobody worries about such matters “in the Colony”. When she returns to work at the modernised bar in Christminster, she and Jude spend the night together. The situation is morally problematic: she is technically bigamous – married to two men at the same time. But Jude has a sexual encounter with her that night (about which he later feels ambivalent). Actually, they are married to each other, but since she is also married to someone else (illegally) Jude is guilty by association. Jude however has the slim moral consolation that he does not know she is married to someone else until the next morning.

Jude and Sue spend a number of years living together even though they are not married – during which time they have two children. Hardy’s ‘argument’ against the conventions surrounding conventional marriage are that this period of their lives represents a ‘marriage of true minds’ [Shakespeare: Sonnet 113] as well as bodies (though these are not mentioned). Jude abd Sue are harassed for defying conventions, but they truly love and understand each other.

However, to live in defiance of society has its costs. They find it difficult to find accommodation, and eventually Sue undergoes a religious conversion that leads her into a state of mind in which she feels compelled to obey the letter of the law which she swore in marrying Phillotson. Since she does not love him and feels physically repelled by him, this a form of masochistic self-punishment.

In reaction to this turn of events, Jude does the same thing in re-marrying Arabella – a woman who he does not love, and the results are similarly negative. Hardy is using elements of the sensation novel to highlight his criticisms of the conventions and taboos surrounding marriage. The sensation elements are – bigamy, people ‘living in sin’, children born out of wedlock, and even the murder of children and suicide at the hands of Little Father Time.

Education

The most important secondary theme of the novel is education – and its relation to social class. Jude is the brightest student of the schoolmaster Phillotson, who at the start of the novel is leaving Marygreen to go to Christminster (Oxford) with the ambition of graduating and becoming a clergyman. Hardy accurately captures the relationship between the church and higher education that existed at that time. The sons of middle and upper class families would be privately educated, then expected to go to university as a natural step towards joining the professions – the church, law, medicine, or the army.

Phillotson does not make the grade. He remains a school teacher, and is even demoted to a teaching assistant because of his unorthodox personal life when he condones Sue’s leaving him to live with Jude. This is frowned upon socially, and it is significant that one of his reasons for re-marrying Sue is that it will enhance his chances of professional promotion.

Jude is a similar case – trapped as he is in an upper working class existence, He has the natural talents to teach himself Latin and Greek, which at that time were thought to be the natural subjects of study in what we now call higher education. As a stonemason he knows he has little chance of escaping his social status, yet he is aware that some provision was being made for working students in the universities

Once again Hardy was entirely accurate historically. Ruskin College Oxford was established in 1899 for the education of working men, and the Cambridge ‘extension classes’ were instituted around the same time – though these were to ‘offer’ academic lectures to working people, rather than enrolling them as students who might graduate.

Jude is enterprising enough to write to one of the college masters for advice on gaining entry – only to be rebuffed by a reply telling him he would do better to remain in his present station. Jude is mortified by this response, and it contributes to his growing sense of disillusionment.

Ultimately he is employed in repairing the stonework of the very buildings that have housed the rejection of him intellectual aspirations. The tragic decline of his hopes reaches its nadir when he denounces the former university luminaries who were formerly his cultural heroes.

This thwarting of intellectual ambitions, combined with the problems of his personal life, contribute powerfully to the tragic sense of resolution in the novel. This double sense of disappointment for the characters may be one of the reasons many readers find the novel a difficult literary experience to endure.

Jude the Onscure – study resources

![]() Jude the Obscure – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

Jude the Obscure – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Jude the Obscure – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

Jude the Obscure – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

![]() Jude the Obscure – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Jude the Obscure – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Jude the Obscure – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Jude the Obscure – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Jude the Obscure – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

Jude the Obscure – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Jude the Obscure – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

Jude the Obscure – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() Jude the Obscure – York Notes – Amazon UK

Jude the Obscure – York Notes – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

Jude the Onscure – chapter summaries

Part First- at Marygreen

I – i Richard Phillotson takes leave of his favourite pupil Jude Fawley as he goes to Christminster to pursue his ambition of obtaining a degree and becoming a clergyman.

I – ii Farmert Troutham beats and sacks Jude from his job of scaring birds off the corn. Jude’s great-aunt reproaches him, and he feels he does not want to be grown up. He walks out of the village to look towards Christminster.

I – iii Jude looks on Christchurch from afar, investing it with romantic powers. A group of wagoners he meets reinforce the notion that life there is lived on a higher plane.

I – iv The quack physician Vilbert promises to bring Jude his old Latin and Greek primers – but fails to do so. Jude writes to Phillotson for grammar guides, but is disappointed when they do not offer simple formulas for translation.

I – v Jude expands his aunt’s bakery business and reads classics whilst making his deliveries. He then becomes an apprentice stonemason in a nearby town.

I – vi Whilst dreaming of Christminster Jude meets Arabella when she throws a pig’s penis at him. He is powerfully attracted to her.

I – vii Next day despite his wish to study, he goes out with Arabella and they very rapidly become close. Arabella discusses her success with friends, who advise her to secure such a good prospect of marriage by entrapment.

I – viii Arabella flirts with Jude and leads him on. Arranging for her parents to be absent, she and Jude end up in her house alone at night – upstairs.

I – ix Two months later Arabella announces that she is pregnant. Jude is only nineteen when he marries her. However, she later reveals that she was ‘mistaken’. Jude immediately feels trapped.

I – x Jude and Arabella inefficiently kill the pig they have been fattening. They argue about the origin and the state of their marriage.

I – xi Next day they quarrel again. Jude feels that his marriage is a disaster. He learns from his aunt that bad marriages are a feature of the Fawley family. He thinks of suicide, then gets drunk. When he arrives home Arabella has left – and she emigrates to Australia with her parents.

Part Second – Christminster

II – i Three years later Jude arrives in Christminster (prompted by a photo of Sue Bridehead, his cousin). He wanders through the city at night, invoking the spirit of its former luminaries.

II – ii Jude looks for work as a stonemason and also locates Sue Bridehead. He has promised his aunt he will not pursue any sort of romantic liaison with her

II – iii Jude traces Sue to a Sunday service in church, but still does not approach her, mindful of his still being married. Sue buys two figures of pagan gods Venus and Apollo and keeps them in her room.

II – iv Jude is consumed by his sexual desire for Sue, but he still regards his marriage vows as a hindrance – until he gets a note form Sue introducing herself as his cousin. They visit Phillotson, who goes on to hire Sue as an assistant teacher.

II – v Sue is successful as a teacher, and Phillotson begins to develop a romantic interest in her. Jude is disappointed, but feels he is hamstrung because of his marriage to Arabella.

II – vi Jude is warned again by his aunt to stay away from Sue. He despairs of his plans to become a student, and receives a crushing reply to a letter requesting advice from a college Master.

II – vii Jude is completely despondent. He resorts to drink, recites Latin in the pub, and goes back to. Marygreen, where he talks about joining the church.

Part Third – at Melchester

III – i Jude and Sue both move to Melchester to study. She tells him she is engaged to Phillotson, who she will marry after her two years of study.

III – ii< Jude and Sue spend a day in the countryside and miss the last train home. They stay overnight in a shepherd’s cottage.

III – iii The next day Sue is reprimanded by her college for staying out. She escapes from confinement, crosses a river, and goes to Jude, who dresses her in his spare clothes.

III – iv Sue tells Jude about her sexless relationship with a young undergraduate. They exchange criticisms of Christminster, and she promises not to vex him with her religious scepticism.

III – v Sue moves to Shaston a nearby town and she is dismissed from the college for disgraceful behaviour with Jude. He visits her, even though she is very capricious towards him. He has still not told her he is married.

III – vi Richard Phillotson has also moved to Shaston. He visits Melchester and learns that Sue has been expelled. At the cathedral he meets Jude, who explains the truth about what happened. Jude meets Sue and tells her about Arabella. They part as friends, not lovers.

III – vii Sue decides to marry Phillotson, and asks Jude to give her away at the wedding. She rehearses the ceremony with Jude in an empty church.

III – viii On a visit back to Christminster Jude meets Arabella working in a modernised pub. She persuades him to stay overnight in a nearby village.

III – ix Next day Arabella reveals that she contracted a bigamous marriage whilst in Australia. They part inconclusively. He meets Sue and they travel to Marygreen where their aunt is ill. Sue reveals that whilst Phillotson is honourable, she regrets marrying him. Jude gets a letter from Arabella, telling him she is re-joining her Australian husband in London

III – x Jude visits the composer of an affecting hymn, hoping to share spiritual confidences – only to find him setting up a wine franchise.

Part Fourth – at Shaston

IV – i Jude visits Sue at her school in Shaston. They are very close, but then she capriciously makes him leave.

IV – ii Jude’s aunt dies. He meets Sue for the funeral. She reveals her ‘repugnance’ for Phillotson, and she feels trapped in the conventions of marriage.

IV – iii Jude cannot reconcile his sexual desire for Sue with his religious aspirations – so he burns his books. Sue asks Phillotson if she can go to live with Jude. They exchange notes between their classrooms discussing the matter.

IV -iV Phillotson consults his friend Gillingham, who advises him to avoid scandal. But Phillotson has come round to a full understanding and acceptance of Sue’s position, and he agrees to let her leave.

IV – v Jude and Sue elope together. She insists that they are to be ‘just ‘good friends’ and she behaves in a tantalising, contradictory manner towards him. They stay in separate rooms. Arabella has meanwhile asked for a divorce.

IV – vi Phillotson is asked to resign because of the scandal, but he refuses and defends himself at a public enquiry, then becomes ill. Sue visits him compassionately He asks her to stay, but she refuses – so he thinks to divorce her.

Part Fifth – at Aldbrickham

V – i The following year both Arabella’s and Phillotson’s divorces become absolute, but Sue does not want to marry Jude. They live together chastely, in separate rooms in the same house.

V – ii Arabella calls at the house asking for help. When Jude offers to see her, Sue puts up a jealous protest, and in the end offers herself sexually to Jude if he agrees not to help Arabella. Next day Sue exchanges views on Jude and marriage with Arabella, who is going back to her Australian husband.

V – iii Sue and Jude agree to delay getting married. A letter from Arabella reveals the existence of Jude’s son, who turns up the very next day – an old man in a boy’s body. Sue agrees to be like a mother to him.

V – iv Sue and Jude go off to the registry office to get married, but they are frightened off by the bad state of other couples there. They go into a church to watch a religious ceremony and come to the same conclusion – that for them marriage would be a dangerous and bad risk.

V – v Arabella and her husband see Sue and Jude at an agricultural fair. Despite their closeness, Arabella thinks she intuits Sue’s lack of passion. She buys a quack love philtre from Vilbert.

V – vi Sue and Jude go secretly to London and let it be known they are married. They secure a church restoration commission together, but are dismissed because the locals think they are not married. Jude. Is forced to auction the family furniture.

V – vii Three years later Sue has two children, Jude is ill, and they have the widow Endlin living with them. Arabella, now a widow, meets Sue whilst she is selling ginger cakes at an agricultural fair at Kennetbridge.

V – viii Driving back from the fair, Arabella decides she wants Jude back again. She meets Phillotson, who is living in reduced circumstances. Jude decides he wants to go back to Christminster.

Book Sixth – at Christminster again

VI- i Jude and family arrive in Christminster on Founders’ Day and he is humiliated again over his academic ‘failure’ They cannot find accommodation, and Sue is asked to leave one house because she admits to not being married.

VI – ii Father Time reproaches Sue for having so many children, then he hangs her son and daughter and himself ‘because we are so many’. When the children are buried Sue wants to open the coffins to see them one last time. Later the same day she gives birth to a dead child.

VI – iii Sue and Jude recover financially, but Sue falls into intellectual despair and wishes to punish herself. She feels that their relationship has been wrong, self-indulgent, and that she really still belongs to Phillotson. She and Jude argue over this reversal in her beliefs. She insists that Jude leave her and that they revert to being just friends.

VI – iv Phillotson is brought abreast of events by Arabella. He thinks to accept Sue back again, and writes to tell her so. Sue announces to Jude that she is going to re-marry Phillotson, even though she does not love him.

VI – v Sue returns to Phillotson, but is forcing herself on principle. He plans a wedding for the next day. Widow Edlin thinks it is an ill-advised venture. They marry in a joyless manner, and Phillotson accepts that the marriage will be loveless and sexless – but good for his career prospects.

VI – vi Arabella argues with her father and asks Jude for temporary shelter. She brings him news of Sue’s marriage, which sends him back to the public house to drown his sorrows. Arabella gets him drunk, then seduces him.

VI – vii Arabella moves Jude into her father’s house with an intention of re-marrying him. She organises an all-night drinking party, then the following morning Jude marries her for a second time whilst he is still drunk.

VI – viii Jude falls ill, and gets Arabella to write to Sue, asking to see her again. But Arabella doesn’t post the letter. Jude goes in the rain to see Sue. They reproach each other, declare their enduring love, then separate.

VI – ix Arabella meets Jude at the station, and they walk through Christminster whilst he repudiates all his old intellectual heroes. Sue thinks she must make the ultimate sacrifice of making herself sexually available to Phillotson – which she does with great reluctance and distaste.

VI – x Jude becomes ill again. Mrs Edlin tells him about Sue’s capitulation to Phillotson, and it breaks his spirit. Arabella flirts with the quack doctor Vilbert.

VI – xi Arabella checks on Jude, and finds he is dead. She nevertheless goes out to the boating party in Christminster with Vilbert. Two days later Mrs Edlin and Arabella exchange views across Jude’s open coffin. Mrs Edlin reports that Sue is worn down and miserable. Arabella thinks that Sue will not feel any peace until death finds her.

Jude the Obscure – principal characters

| Jude Fawley | young stonemason with academic ambitions |

| Sue Bridehead | Jude’s free-spirited but frigid cousin |

| Arabella Donn | sensuous daughter of a pig farmer |

| Richard Phillotson | a rather puritanical schoolmaster |

| Little Father Time | Arabella and Jude’s melancholy son |

| Pruscilla Fawley | Jude’s great-aunt |

| Mr Vilbert | a quack physician |

| Mr Cartlett | Arabella’s Australian husband |

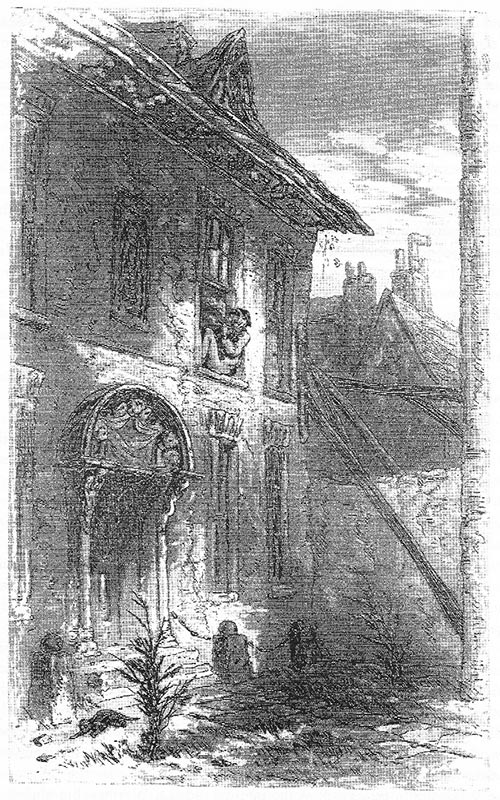

Hardy’s study

reconstructed in Dorchester museum

Jude the Obscure – further reading

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Thomas Hardy: The Tragic Novels – Amazon UK

Thomas Hardy: The Tragic Novels – Amazon UK

![]() Thomas Hardy: The Tragic Novels – Amazon US

Thomas Hardy: The Tragic Novels – Amazon US

![]() A Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

A Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Palgrave Advances in Thomas Hardy Studies – Amazon UK

Palgrave Advances in Thomas Hardy Studies – Amazon UK

Other works by Thomas Hardy

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Woodlanders (1887) Giles Winterbourne, an honest woodsman, suffers with the many tribulations of his selfless love for Grace Melbury, a woman above his station in this classic tale of the West Country. She marries the new doctor, Edred Fitzpiers, but leaves him when she learns he has been unfaithful. She turns instead to Giles, who nobly allows her to sleep in his house during stormy weather, whilst he sleeps outside and brings on his own death. It’s often said that the hero of this novel is the woods themselves – so deeply moving is Hardy’s account of the timbered countryside which provides the backdrop for another human tragedy and a study of rural life in transition.

The Woodlanders (1887) Giles Winterbourne, an honest woodsman, suffers with the many tribulations of his selfless love for Grace Melbury, a woman above his station in this classic tale of the West Country. She marries the new doctor, Edred Fitzpiers, but leaves him when she learns he has been unfaithful. She turns instead to Giles, who nobly allows her to sleep in his house during stormy weather, whilst he sleeps outside and brings on his own death. It’s often said that the hero of this novel is the woods themselves – so deeply moving is Hardy’s account of the timbered countryside which provides the backdrop for another human tragedy and a study of rural life in transition.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Thomas Hardy – web links

![]() Thomas Hardy at Mantex

Thomas Hardy at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, book reviews. bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

![]() The Thomas Hardy Collection

The Thomas Hardy Collection

The complete novels, stories, and poetry – Kindle eBook single file download for £1.29 at Amazon.

![]() Thomas Hardy at Project Gutenberg

Thomas Hardy at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of digital formats.

![]() Thomas Hardy at Wikipedia

Thomas Hardy at Wikipedia

Biographical notes, social background, the novels and literary themes, poetry, religious beliefs and influence, biographies and criticism.

![]() The Thomas Hardy Society

The Thomas Hardy Society

Dorset-based site featuring educational activities, a biennial conference, a journal (three times a year) with links to the texts of all the major works.

![]() The Thomas Hardy Association

The Thomas Hardy Association

American-based site with photos and academic resources. Be prepared to search and drill down to reach the more useful materials.

![]() Thomas Hardy on the Internet Movie Database

Thomas Hardy on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors, actors, production features, box office, film reviews, and even quizzes.

![]() Thomas Hardy – online literary criticism

Thomas Hardy – online literary criticism

Small collection of academic papers and articles ‘favoring signed articles by recognized scholars and articles published in peer-reviewed sources’.

![]() Thomas Hardy’s Wessex

Thomas Hardy’s Wessex

Evolution of Wessex, contemporary reviews, maps, bibliography, links to other web sites, and history.

© Roy Johnson 2016

More on Thomas Hardy

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first.

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first. Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Sons and Lovers

Sons and Lovers Women in Love

Women in Love

But none of these artists were working class, and before long Party apparatchiks were calling for the suppression of their work and demanding art that followed the Party line. Since the party had a monopoly of the means of production and even the supply of paper, they got what they called for. The result was worthless propaganda of the ‘boy meets tractor’ variety.

But none of these artists were working class, and before long Party apparatchiks were calling for the suppression of their work and demanding art that followed the Party line. Since the party had a monopoly of the means of production and even the supply of paper, they got what they called for. The result was worthless propaganda of the ‘boy meets tractor’ variety.

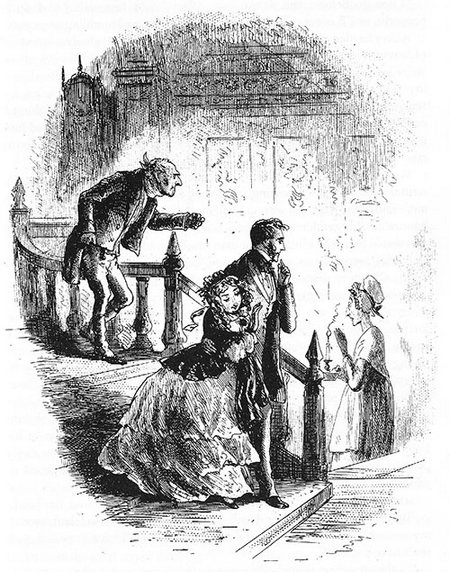

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp, pretending that Charlotte is ill and in a hospital. He takes Lolita to a hotel, where he meets a strange man (later revealed to be Clare Quilty), who seems to know who he is. Humbert attempts to use sleeping pills on Lolita so that he may molest her without her knowledge, but they have little effect on her. Instead, she consciously seduces Humbert the next morning. He discovers that he is not her first lover, as she had sex with a boy at summer camp. Humbert reveals to Lolita that Charlotte is actually dead; Lolita has no choice but to accept her stepfather into her life on his terms.

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp, pretending that Charlotte is ill and in a hospital. He takes Lolita to a hotel, where he meets a strange man (later revealed to be Clare Quilty), who seems to know who he is. Humbert attempts to use sleeping pills on Lolita so that he may molest her without her knowledge, but they have little effect on her. Instead, she consciously seduces Humbert the next morning. He discovers that he is not her first lover, as she had sex with a boy at summer camp. Humbert reveals to Lolita that Charlotte is actually dead; Lolita has no choice but to accept her stepfather into her life on his terms. One day in 1952, Humbert receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is married, pregnant, and in desperate need of money. Humbert goes to see Lolita, giving her money and hoping to kill the man who abducted her. She reveals the truth: Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte’s and the writer of the school play, checked her out of the hospital and attempted to make her star in one of his pornographic films; when she refused, he threw her out.

One day in 1952, Humbert receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is married, pregnant, and in desperate need of money. Humbert goes to see Lolita, giving her money and hoping to kill the man who abducted her. She reveals the truth: Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte’s and the writer of the school play, checked her out of the hospital and attempted to make her star in one of his pornographic films; when she refused, he threw her out.