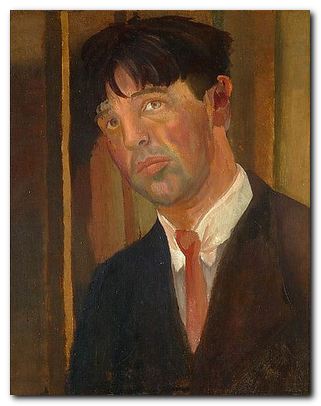

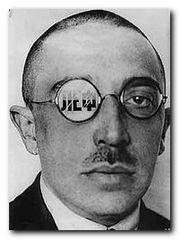

English modernist painter and war artist

Richard Nevinson – (1899-1946) was an English artist of the early modernist period, the second child of Suffragette-supporters and Christian Socialists who lived in Hampstead. His mother was a teacher and his father (an Oxford classics graduate) was a war correspondent with the Daily Chronicle and the Manchester Guardian. Nevinson was generally unhappy and often ill as a child, and was particularly undistinguished at school. When he was thirteen his father made the disastrous decision to send him to a low-ranking public school, where he endured three pointless years of learning virtually nothing and which left him emotionally scarred, with an enduring hatred of ‘the national code of snobbery and sport’.

The only thing for which he had any aptitude was art, so in 1907 he was sent to St John’s Wood School of Art. This opened up the world of bohemian culture to him, and although his painting and drawing were still undeveloped he spent time drinking in the Cafe Royal in Regent Street with Arthur Symonds who was a friend of his father.

He was supposed to be preparing for entry into the Royal Academy Schools, but when he saw a publication of drawings by artists at the Slade, he knew that this was where he wanted to be. The Slade School of Art was part of University College, London and his contemporaries included Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, and Dora Carrington.

However, when he got there he felt lonely and isolated, but became close friends with Mark Gertler – both of them ‘outsiders’ and both fond of the music halls. But whilst Gertler progressed rapidly and had some remarkable early success, Nevinson had yet to find his own n distinctive style. He painted scenes of railway sidings, factories, and gasometers in the north London suburbs.

Nevinson and Gertler began exhibiting with some degree of success in 1911. They discussed art together all the time, but their friendship was ended not by theories of art but by Dora Carrington. Both of them were paying court to her at the same time, and she (terrified of any possible sexual contact at that stage of her life) was playing one off against the other. Nevinson was older and more experienced, Gertler was better looking and more successful. In the end she chose Gertler – not that it brought him much satisfaction.

After Nevinson’s first year, and following the Dora Carrington problem, he felt that the Slade had nothing more to offer him, and he moved north to Bradford where he felt better painting pictures of mills, factories, and coal mines. But the triangular struggle with Gertler and Carrington continued nevertheless. He then moved to Paris and studied for a while at the Academie Julien. He copied paintings in the Louvre, shared a studio with Modigliani for a while, and met Lenin who at that time was living in exile.

Returning to London in 1913, Nevinson was plunged back into despair by his jealous obsession with Carrington, and eventually had a complete breakdown. He recovered in a health spa in Buxton, after which he was something of a changed man. He threw in his lot with Wyndham Lewis and the other English futurists who set themselves up as an alternative to Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops.

Unfortunately, this move only cut him off even further from the artistic success he sought. The Vorticists (as they called themselves) became mired in factional disputes, they lost their patron, and disappeared rapidly into obscurity, despite issuing Manifestos and calling for revolutions. Their timing couldn’t have been worse or more ironic, because just across the English Channel real wars and revolutions were going on.

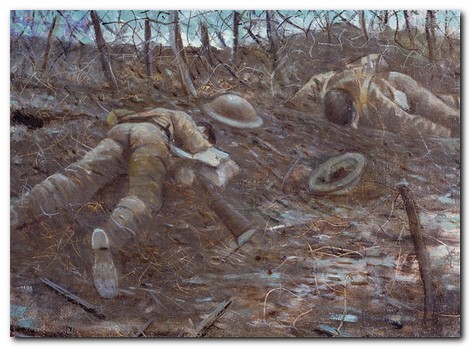

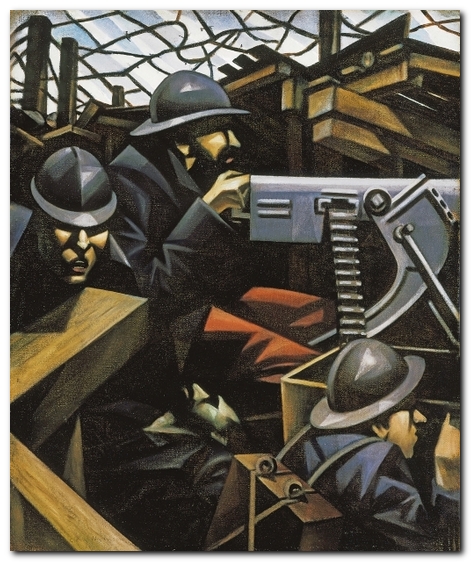

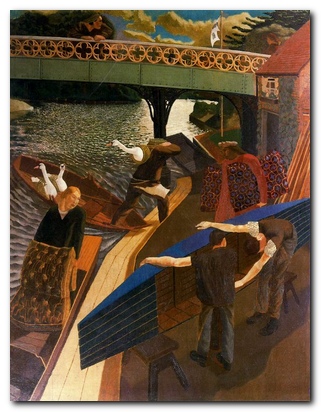

Nevinson joined the Ambulance Brigade and worked with his father in the makeshift field hospitals of northern France. The scenes of horror he encountered there were so bad that he returned to England in January 1915 and never went back into combat. He transformed these experiences into what was to become his greatest work, La Mitrailleuse, and the success of this work alone led to a one man show at the Leicester Galleries which was a sell out.

However, his shattered nerves were not bad enough to prevent his being re-conscripted. Various wires were pulled and people of influence contacted, and he was returned to the conflict as a war artist – but with no status and no salary. However, many of the paintings which came out of these experiences were criticised and even censored because they were not considered sufficiently patriotic.

After the war Nevinson (like Paul Nash) became ‘a war artist without a war’. His post-war years were tortured – mainly by his rancour at not being celebrated. He reverted to painting in a realistic style, and produced some dramatic cityscapes of New York, Paris, and London which were well received. During the Second World War he worked as a stretcher-bearer in London throughout the Blitz, in which time his own studio and the family home in Hampstead were hit by bombs. He suffered a stroke which paralysed his right hand, and even though he taught himself to paint with his left hand he died somewhat embittered in 1946.

![]() Richard Nevinson: Modern War Paintings – Amazon UK

Richard Nevinson: Modern War Paintings – Amazon UK

![]() Richard Nevinson: Modern War Paintings – Amazon US

Richard Nevinson: Modern War Paintings – Amazon US

![]() A Crisis of Brilliance – Amazon UK

A Crisis of Brilliance – Amazon UK

![]() A Crisis of Brilliance – Amazon US

A Crisis of Brilliance – Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2015

More on art

More on media

More on design

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice.

However, it should perhaps be remembered that many visual artists, from art-college onwards, come badly unstuck when it comes to expressing their ideas in words. That’s why theories of constructivism and any other movement should be founded on what is produced, not what is said. This is one of the weaknesses of extrapolating aesthetic theories from documents such as those reproduced here. Much huffing and puffing can be expended on whatever artists said about their art, rather than what they produced. But these are theories based on opinions rather than material practice. Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.

Taking a sympathetic attitude to the early efforts of these artists to develop a revolutionary approach to art, it’s interesting to note that they thought subjective individual expression ought to be replaced by collective works. They also fondly imagined that the working class would unerringly prefer the most imaginative and original works over traditional offerings. This was a period in which the term ‘easel painting’ was used in a tone of sneering contempt. The fact that they were largely ignored by the class for whom they thought they were fighting this aesthetic war in no way diminishes their achievements.