tutorial, study guide, commentary, further reading

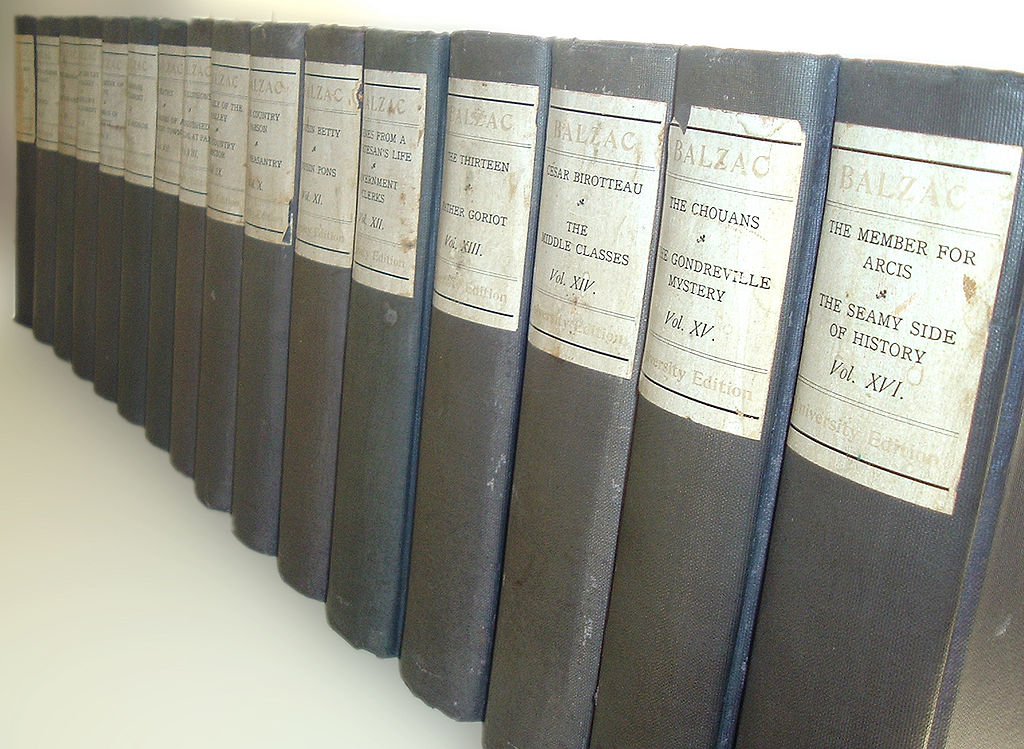

A Commission in Lunacy (1836) is one story from the many which make up La Comedie Humaine. Its original French title was L’Interdiction and it features two characters – Eugene de Rastignac and Horace Bianchon – who appear in many of Balzac’s other novels and stories which constitute the fictional world he generated.

A Commission in Lunacy – commentary

Structure

This story is a very brief episode in the vast work that is The Comedie Humaine. It has a simple but very powerful structure. Basically, it is in two parts, contrasting Greed and Honour, pivoting around Principle. It can also be seen as the ‘new’ values of vulgar social ambition contrasted with old-fashioned patrician modesty and restraint. In briefest terms, it is Self-interest versus Self-sacrifice.

We are introduced to a fashionable society woman who wishes to bring legal proceedings against her estranged husband. Her damning case against him is discussed in close detail.

The judge who will examine the case is then presented as a somewhat saintly figure – neglected by himself and the state, he spends his spare time and money helping the poor.

He then interviews both parties to the dispute. First the wife, who is exposed as a self-indulgent and money-grabbing villain. Then her husband, who is revealed as a man of integrity who has voluntarily repaid a family debt of honour.

Characters

The principal characters in the story illustrate perfectly the complex nature of La Comedie Humaine – its interdependent associations and overlapping events, as well as the recurrent appearances of its individuals.

Eugene de Rastignac and Horace Bianchon are old friends, both former student lodgers at the Maison Vauquer which features in the novel Old Goriot (1834). Rastignac was an ambitious student of law who has risen rapidly via social connections to become an influential politician.

Horace Bianchon was once a humble student of medicine who has mixed with raffish arrivistes but who has never lost his Hippocratic principles of helping those in need. He has risen to become a leading medical authority in fashionable Paris, and he appears in several other Balzac novels, including Cousin Bette (1846) and Lost Illusions (1837-1843).

Popinot the judge is Bianchon’s uncle, and he also appears in a number of other episodes in La Comedie Humaine. So too does the judge who replaces him in the final pages of the story. Camusot has recently arrived in Paris from the provinces: he presides over the report on the d’Espard case and decides in favour of the Marquis.

Interestingly, we learn in another novel Scenes from a Courtesan’s Life that Camusot is assisted in reaching this judgement by Lucien Rubempré, who also appears in several volumes of La Comedie Humaine.

What is a ‘commission in lunacy’?

This expression is not merely a picturesque example of translation. The French title of the story is L’Interdiction. The Commission in Lunacy was a body established (in the UK) in 1845 to oversee the treatment of people who were deemed mentally ill. It was a board comprising legal and medical experts, plus a cohort of laymen.

The main theme

At the heart of this story is a conflict between what Balzac sees as two sets of social values. The Marquise is greedy, self-obsessed, and full of vulgar social ambition. Her husband the Marquis on the other hand represents self-denial, honesty, and a respect for an old-fashioned but honourable system of values.

The Marquise is obsessed with appearances: she lies about her age and doesn’t even wish to be seen with her own teenage sons in case this reveals how old she is. She lives in luxurious surroundings, but wants to have her husband committed as a lunatic so that she can take over his money. She constructs what adds up to a pack of lies and distortion to defame him in court.

The Marquis on the other hand lives in a simple (but tasteful) fashion: he brings up his two sons; and he has lived within his means for twelve years so as to pay back to the Jeanrenaud family wealth that has been unfairly seized from them by his own grandfather. Meanwhile he is working (and providing employment for others) on a scholarly research project which has the backing of a distinguished Parisian publishing house.

The general picture

Balzac is renowned for his insights into the social, political, legal, and economic workings of society. Indeed Frederick Engels said of him “I have learned more from Balzac than from all the professional historians, economists, and statisticians put together”. Balzac exposes how society is governed via money, law (especially inheritance), property, political power, and ruling elites.

What is not so frequently remarked upon is how realistically he renders the material fabric of the living world he creates. He has acute powers of observation, and can depict both the architectural history of someone’s housing, plus their moral and aesthetic attitudes as revealed by interior decor.

[Monsieur d’Espard] restored the woodwork to those brown tones beloved in Holland, and by the old Parisian bourgeoisie, which, in our day, afford such fine effects to painters of genre. The walls we hung with plain papers which harmonised with the woodwork. The windows had curtains of some material that was not costly, and yet was chosen in a manner to produce an effect in keeping with the general harmony. The furniture was choice and well arranged.

Whoever entered these rooms could not fail to be conscious of a peaceful, tranquil feeling, inspired by the stillness and silence that reigned there, by the quietness and symphony of the colouring

Balzac – selected reading

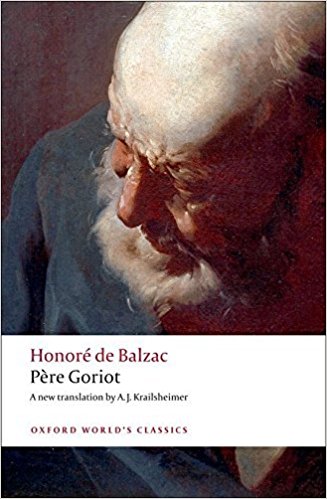

The best current editions of the major novels are those published in the Oxford World’s Classics paperback series. Each volume contains a critical introduction, a note on the text, a bibliography of further reading, a chronology of Honore de Balzac, and most importantly a series of explanatory notes giving historical, geographical, and scientific information about details mentioned in the text.

Pere Goriot – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

Eugenie Grandet – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

Cousin Bette – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Ursule Mirouet – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Selected Stories – NYRB – Amazon UK

Cambridge Companion to Balzac – Cambridge UP – Amazon UK

A Commission in Lunacy – plot summary

Eugene de Rastignac and Horace Bianchon discuss the fashionable socialite Marquise d’Espard. Bianchon warns against women of this type, whilst Rastignac thinks a connection with her will assist his social ambitions.

Jean-Jules Popinot is a conscientious but neglected judge who dresses badly. He devotes his early mornings to supporting the poor and destitute. His nephew Bianchon arrives to discuss the petition made by the Marquise to have her husband declared insane.

The petition claims that Marquis d’Espard has become demented and is under the psychic influence of Mme Jeanrenaud and her son. The Marquis has also become obsessed with the subject of China, has taken his two sons away, and given Mme Jeanrenaud a million francs. Bianchon persuades his uncle to see the Marquise.

The Marquise devotes her life to looking young and maintaining an exclusive salon. She lives in luxurious surroundings and has taken on Rastignac as a protégé.

The Marquise explains how she was abandoned by her husband when she was twenty-two. But Popinot unpicks her arguments and exposes her as a greedy gold-digger.

The fat Mme Jeanrenaud visits Popinot and rejects the claims made against her. Popinot then visits the Marquis who lives modestly and tastefully in the Latin quarter. He is a patrician of the old school.

Questioned by Popinot, the Marquis explains that he has been repaying a debt of honour caused by his family’s illegal seizure of Jeanrenaud’s assets. He proposed this restitution to his young wife, but she refused to participate. He also explains his major research project into Chinese culture and history.

Popinot writes a report exonerating the Marquis to the Commission in Lunacy, but he is unable to present it in court, because he has compromised himself by socialising with the applicant, the Marquise. He is being replaced on the case by a new provincial lawyer Camusot. However, Popinot is awarded the Legion of Honour.

© Roy Johnson 2018

A Commission in Lunacy – characters

| Eugene de Rastignac | a socially ambitious man-about-town |

| Horace Bianchon | a young and principled Parisian physician |

| Jean-Jules Popinot | a scrupulous and neglected lower court judge |

| Marquis d’Espard | an old-fashioned and high-principled aristocrat |

| Marquise d’Espard | his estranged wife, a self-indulgent socialite |

| Mme Jeanrenaud | the overweight head of family disenfranchised by the d’Espards |

More on Honore de Balzac

More on literary studies