tutorial, characters, resources, film, writing

The Portrait of a Lady (1881) is generally regarded as the masterpiece of James’s middle period. Isabel Archer, a young American woman with looks, wit, and imagination, arrives to discover Europe. She sees the world as “a place of brightness, of free expression, of irresistible action”. Turning aside from suitors who offer her their wealth and devotion, she follows her own path.

But that way leads to disillusionment and a future as constricted as “a dark narrow alley with a dead wall at the end”. James explores here one of his favourite themes – the New World in contest with the Old. In a conclusion that is one of the most moving in modern fiction, Isabel is forced to make her final choice.

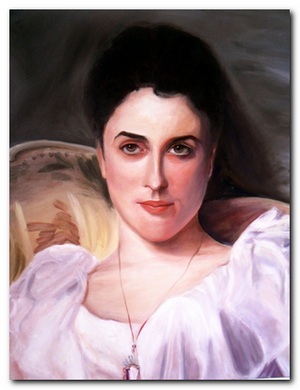

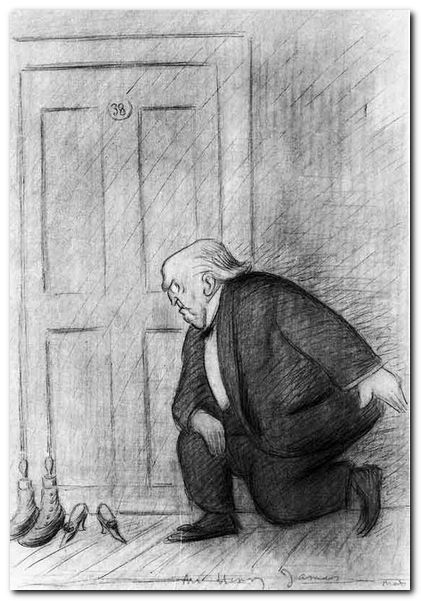

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

The Portrait of a Lady – plot summary

Isabel Archer, originally from Albany, New York, is invited by her maternal aunt, Lydia Touchett, to visit Lydia’s rich husband Daniel at his estate near London, following the death of Isabel’s father. There, she meets her cousin Ralph Touchett, a friendly invalid, and the Touchetts’ robust neighbor, Lord Warburton.

Isabel later declines Warburton’s sudden proposal of marriage. She also rejects the hand of Caspar Goodwood, the charismatic son and heir of a wealthy Boston mill owner. Although Isabel is drawn to Caspar, her commitment to her independence precludes such a marriage, which she feels would demand the sacrifice of her freedom. The elder Touchett grows ill and, at the request of his son, leaves much of his estate to Isabel upon his death.

With her large legacy, Isabel travels the Continent and meets an American expatriate, Gilbert Osmond, in Florence. Although Isabel had previously rejected both Warburton and Goodwood, she accepts Osmond’s proposal of marriage. She is unaware that this marriage has been actively promoted by the accomplished but untrustworthy Madame Merle, another American expatriate, whom Isabel had met at the Touchetts’ estate.

With her large legacy, Isabel travels the Continent and meets an American expatriate, Gilbert Osmond, in Florence. Although Isabel had previously rejected both Warburton and Goodwood, she accepts Osmond’s proposal of marriage. She is unaware that this marriage has been actively promoted by the accomplished but untrustworthy Madame Merle, another American expatriate, whom Isabel had met at the Touchetts’ estate.

Isabel and Osmond settle in Rome, but their marriage rapidly sours due to Osmond’s overwhelming egotism and his lack of genuine affection for his wife. Isabel grows fond of Pansy, Osmond’s presumed daughter by his first marriage, and wants to grant her wish to marry Ned Rosier, a young art collector. The snobbish Osmond would rather that Pansy accept the proposal of Warburton, who had previously proposed to Isabel. Isabel suspects, however, that Warburton may just be feigning interest in Pansy to get close to Isabel again.

The conflict creates even more strain within the unhappy marriage. Isabel then learns that Ralph is dying at his estate in England and prepares to go to him for his final hours, but Osmond selfishly opposes this plan. Meanwhile, Isabel learns from her sister-in-law that Pansy is actually the daughter of Madame Merle, who had an adulterous relationship with Osmond for several years.

Isabel visits Pansy one last time, who desperately begs her to return some day, something Isabel reluctantly promises. She then leaves, without telling her spiteful husband, to comfort the dying Ralph in England, where she remains until his death.

Goodwood encounters her at Ralph’s estate and begs her to leave Osmond and come away with him. He passionately embraces and kisses her, but Isabel flees. Goodwood seeks her out the next day, but is told she has set off again for Rome. The ending is ambiguous, and the reader is left to imagine whether Isabel returned to Osmond to suffer out her marriage in noble tragedy (perhaps for Pansy’s sake) or whether she is going to rescue Pansy and leave Osmond.

Study resources

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

The Portrait of a Lady – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

The Portrait of a Lady – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

The Portrait of a Lady – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

The Portrait of a Lady – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Portrait of a Lady – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – Cliff’s Notes – Amazon UK

The Portrait of a Lady – Cliff’s Notes – Amazon UK

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Portrait of a Lady – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – Kindle eBook edition

The Portrait of a Lady – Kindle eBook edition

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – eBook version at Project Gutenberg

The Portrait of a Lady – eBook version at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – audioBook version at LibriVox

The Portrait of a Lady – audioBook version at LibriVox

![]() Preface to The Portrait of a Lady – for the 1910 New York edition

Preface to The Portrait of a Lady – for the 1910 New York edition

![]() The Portrait of a Lady – audio book (abridged, with music)

The Portrait of a Lady – audio book (abridged, with music)

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() The Ladder – A Henry James web site

The Ladder – A Henry James web site

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

The Portrait of a Lady – characters

| Lord Warburton | English peer and landowner |

| Daniel Touchett | Vermont banker |

| Ralph Touchett | young invalid – Isobel’s cousin |

| Lydia Touchett | Ralph’s sister in Florence |

| Isabel Archer | Ralph’s (maternal) cousin |

| Lilian Archer | Isobel’s married sister |

| Edith Archer | Isobel’s married sister |

| Edmund Ludlow | Lilian’s husband |

| Caspar Goodwood | rich Boston industrialist |

| Henrietta Stackpole | feminist and journalist |

| Bunchie | Terrier dog |

| Miss Molyneux | Lord Warburton’s elder sister |

| Mr Bantling | Bachelor friend of Ralph’s |

| Lady Pensil | Bantling’s sister |

| Miss Climbers | friend of Henrietta Stackpole |

| Madame Merle | friend of Mrs Touchett’s from Florence |

| Mr & Mrs Luce | friends of Mrs Touchett’s in Paris |

| Edward Rosier | aesthete living in Paris |

| Gilbert Osmond | asthete living in Italy for 20 years |

| Pansy Osmond | Osmond’s 15 year old daughter |

| Countess Gemini | Osmond’s sister |

| Gardencourt | Mr Touchett’s estate |

| Lockleigh | Lord Warburton’s estate |

| Palazzo Crescentini | Mrs Touchett’s home |

The Portrait of a Lady – film version

Jane Campion 1996 – Nicole Kidman and John Malkovich

![]() See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

The Portrait of a Lady – further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on Henry James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Part III. Their relationship comes to life again, and Sam proposes marriage to her for a second time. She accepts in principle, even though by doing so she would lose the home and the living Twycott has provided for her. But she needs time to break the news to her son. When she does so, he forbids her to marry Sam because the shame of it would downgrade him in the eyes of his friends. Sophy asks Sam to wait, and he does so for five years, after which he repeats his offer. Sophy renews her appeal to Randolph, who is now an undergraduate at Oxford. He forces her kneel down and swear that she will never marry Sam, claiming that he does this to honour the memory of his father. Five years later Sam has become a prosperous greengrocer. He stands in his shop doorway as Sophy’s funeral procession passes by on its way to her home village. Randolph who has now become a priest scowls at Sam from the mourner’s coach.

Part III. Their relationship comes to life again, and Sam proposes marriage to her for a second time. She accepts in principle, even though by doing so she would lose the home and the living Twycott has provided for her. But she needs time to break the news to her son. When she does so, he forbids her to marry Sam because the shame of it would downgrade him in the eyes of his friends. Sophy asks Sam to wait, and he does so for five years, after which he repeats his offer. Sophy renews her appeal to Randolph, who is now an undergraduate at Oxford. He forces her kneel down and swear that she will never marry Sam, claiming that he does this to honour the memory of his father. Five years later Sam has become a prosperous greengrocer. He stands in his shop doorway as Sophy’s funeral procession passes by on its way to her home village. Randolph who has now become a priest scowls at Sam from the mourner’s coach.