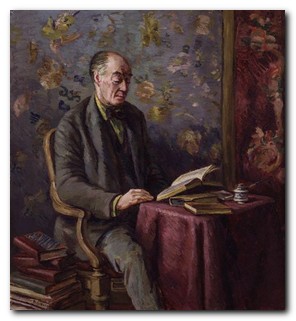

journalist, literary critic, and raconteur

Desmond MacCarthy (full name Charles Otto Desmond MacCarthy) was born in Plymouth, Devon in 1877. He was educated at Eton College, the famous public (that is, private) school, and went on to Trinity College Cambridge in 1894. He became a close friend of G.E Moore, whose Principia Ethica had a profound influence on all those who went on to form the Bloomsbury Group.

He was older than the cohort of Leonard Woolf, Clive Bell, Saxon Sydney-Turner, and Thoby Stephen who all arrived later in 1899 – but because of his close friendship with Moore he re-visited frequently and formed friendships with the younger network. He was also a friend of Henry James and Thomas Hardy.

He married Mary (Molly) Warre-Cornish in 1906 and the next year edited The New Quarterly. Roger Fry asked him to become the secretary for the first Post-Impressionist exhibition he organised at the Grafton Galleries in 1910 – an event which Virginia Woolf described as of such significance that it changed human character. This gave MacCarthy the opportunity to tour Europe, buying paintings by Van Gogh, Cezanne, and Matisse, who at that time were relatively unknown.

During the first world war he served as an ambulance driver in France and he also spent some time in Naval Intelligence. He started writing reviews for the New Statesman in 1917 and went on to become its editor from 1920 to 1927. He wrote a weekly column under the nom de plume of ‘Affable Hawk’. After leaving the New Statesman he went on to be editor of Life and Letters and later succeeded Edmund Gosse as senior literary critic on the Sunday Times.

Although he was a professional man of letters who published a great deal of criticism, he was celebrated in the Bloomsbury Group as a brilliant raconteur and a creative writer of great promise. However, the promise never resulted in the production of the great novel he was always threatening to write. His gifts as a speaker are illustrated by a famous incident from a meeting of the Memoir Club, at which Bloomsbury members would give papers recalling past events and memoirs of fellow members. E.M. Forster recalls:

In the midst of a group which included Lytton Strachey, Virginia Woolf, and Maynard Keynes, he stood out in his command of the past, and in his power to rearrange it. I remember one paper of his in particular – if it can be called a paper. Perched away in a corner of Duncan Grant’s studio, he had a suit-case open before him. The lid of the case, which he propped up, would be useful to rest his manuscript upon, he told us. On he read, delighting us as usual, with his brilliancy, and humanity, and wisdom, until – owing to a slight wave of his hand – the suit-case unfortunately fell over. Nothing was inside it. There was no paper. He had been improvising.

In his autobiography Leonard Woolf, a friend and fellow editor, analyses the reasons for what he sees as the failure of Desmond MacCarthy to fulfil his promise as a creative writer. He acknowledges the fact that MacCarthy published several volumes of well-received literary criticism, but this is seen as lacking a certain moral courage which genuinely creative writers face when they commit themselves to print. This is amusingly coupled to MacCarthy’s pathological procrastination and lack of self-discipline. a view echoed by Quentin Bell in his affectionate memoir of the MacCarthy family:

He would turn up at Richmond [Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s house] for dinner, uninvited very probably, and probably committed to a dinner elsewhere, charm his way out of his social crimes on the telephone, talk enchantingly until the small hours, insist that he be called early so that he might attend to urgent business on the morrow, wake up a little late, dawdle somewhat over breakfast, find a passage in The Times to excite his ridicule, enter into a lively discussion of Ibsen, declare he must be off, pick up a book which reminded him of something which, in short, would keep him talking until about 12.45, when he would have to ring up and charm the person who had been waiting in an office for him since 10, and at the same time deal with the complications arising from the fact that he had engaged himself to two different hostesses for lunch, and that it was now 1 o’clock, and it would take forty minutes to get from Richmond to the West End. In all this Desmond had been practising his art – the art of conversation.

He was knighted in 1951 and died in 1952. He was buried in Cambridge.

Bloomsbury Group – web links

![]() Hogarth Press first editions

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, featuring designs by Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and others.

![]() The Omega Workshops

The Omega Workshops

A brief history of Roger Fry’s experimental Omega Workshops, which had a lasting influence on interior design in post First World War Britain.

![]() The Bloomsbury Group and War

The Bloomsbury Group and War

An essay on the largely pacifist and internationalist stance taken by Bloomsbury Group members towards the First World War.

![]() Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Mini web site featuring photos, paintings, a timeline, sub-sections on the Omega Workshops, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant, and biographical notes.

![]() Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Exhibition of paintings, designs, and ceramics at Toronto University featuring Hogarth Press, Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Quentin Bell, and Stephen Tomlin.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

A rich enthusiast site featuring news of events, exhibitions, new book reviews, relevant links, study resources, and anything related to Bloomsbury and Virginia Woolf

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search the texts of all Woolf’s major works, and track down phrases, quotes, and even individual words in their original context.

![]() A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

An annotated description of Clarissa Dalloway’s walk from Westminster to Regent’s Park, with historical updates and a bibliography.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Annotated tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury, including Gordon Square, University College, Bedford Square, Doughty Street, and Tavistock Square.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

News of events, regular bulletins, study materials, publications, and related links. Largely the work of Virginia Woolf specialist Stuart N. Clarke.

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

A charming sound recording of a BBC radio talk broadcast in 1937 – accompanied by a slideshow of photographs of Virginia Woolf.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephens’ collection of family photographs which became known as the Mausoleum Book, collected at Smith College – Massachusetts.

![]() Bloomsbury at Duke University

Bloomsbury at Duke University

A collection of book jacket covers, Fry’s Twelve Woodcuts, Strachey’s ‘Elizabeth and Essex’.

© Roy Johnson 2000-2014

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

The Complete Critical Guide to D. H. Lawrence

The Complete Critical Guide to D. H. Lawrence Sons and Lovers

Sons and Lovers The Rainbow

The Rainbow Women in Love

Women in Love Lady Chatterley’s Lover

Lady Chatterley’s Lover The Complete Short Stories

The Complete Short Stories The Short Novels

The Short Novels The Complete Poems

The Complete Poems

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth The Reef

The Reef