understanding how stories are told

What is analysing narratives?

Analysing narratives is making a critical assessment of features in a piece of work. This activity goes from making a detailed inspection of grammar and vocabulary, to offering judgements on major issues such as structure and genre.

A narrative is the account of a sequence of events. It’s the term used to describe the whole of a story, a tale, or even a process.

The term is used mainly in literary studies when discussing major genres such as the short story, the novella, and the novel. There are also narrative poems – such as Robert Browning’s The Pied Piper of Hamelin (1842).

A narrative is an account which has a discernable beginning, includes a sequence of events, and an outcome or a conclusion.

Narratives and media

The term narrative is also used for non-literary works. In such cases its used in a general and neutral sense, when the work does not have the consciously engineered structure of written works such as the short story or the novel.

For instance, any of the following can be considered narratives:

- A newspaper report of a natural disaster such as a volcanic eruption

- A television documentary covering the whole of a general election

- The description of a manufacturing process such as car production

The analysis of narratives is a form of study which arose in literary studies, and has been continued in related cultural fields of media studies such as film, television, and even computer games.

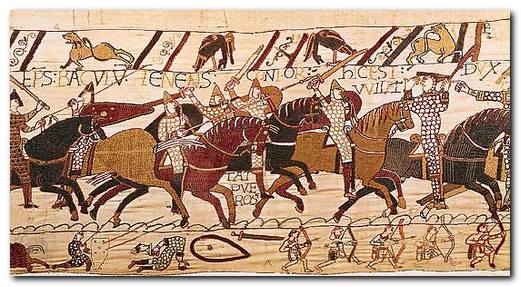

It is even possible to have narrative paintings. The Bayeaux Tapestries for instance provide an account of the Battle of Hastings in 1066, depicting a sequence of its key events, but all presented simultaneously within one frame.

The language of narratives

The term narrative is used to described the whole of the piece of writing or the sequence of its events – as in

The narrative of Great Expectations is one in which Dickens combines all his favourite themes and unites them with a complex plot which is full of dramatic suspense.

The term story is used to describe the content of the narrative – as in

The story of Great Expectations is one of a young boy from a humble country background who becomes a London gentleman. In doing so he loses his moral sense – only to recover himself through painful scenes of redemption.

You can see that this is an extremely compressed summary of the novel which focuses only on its most important theme and excludes any of its smaller details.

The term theme is used to describe the underlying topic or issue of the narrative. This is often of a general or abstract nature, as distinct from the overt subject with which the work deals. It should be possible to express theme in a single word or short phrase such as ‘redemption through suffering’, ‘moral education’, or ‘coming of age’.

The term theme is used to describe the underlying topic or issue of the narrative. This is often of a general or abstract nature, as distinct from the overt subject with which the work deals. It should be possible to express theme in a single word or short phrase such as ‘redemption through suffering’, ‘moral education’, or ‘coming of age’.

The term plot is used to describe the manner in which elements of the narrative have been arranged to create dramatic interest, suspense, and possibly surprise. This arrangement could be the withholding of certain information, rearranging the sequence in which it is revealed, or embedding mysteries which only become clear when a later piece of information is presented.

A surprising turn of events, or the unmasking of a hidden identity are well-known plot devices of traditional fiction. Contemporary readers might feel that such devices have been so over-used as to become poor clichés.

Narrative mode

It is the author who writes the story, But an author can choose to convey events using one of what are called narrative modes. The two simplest are the first person singular (‘I’) and the third person singular (‘he’).

It is also possible to have stories related by multiple narrators. This is a device often used to present events from different perspectives or points of view.

Modern writers have also introduced further complexities into their stories by using what are called unreliable narrators. These are first person accounts given by characters with a limited, distorted, or even mistaken understanding of events.

First person narrators

The author creates a character who tells the story from his or her own point of view. That character may or may not be part of the story. Charles Dickens’ famous novel David Copperfield (1867) is an example of someone telling their own life story and participating in its events as one of the characters in the novel. Dickens is the author, David Copperfield is the narrator, and he is also a character in the story.

F Scott-Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby (1925) is largely concerned with the mysterious and very rich Jay Gatsby, but it is narrated by Nick Carraway, one of his neighbours and also a participating character in the novel.

Fyodor Dostoyevski on the other hand has a first person narrator in Notes from Underground (1864) whose name we never know. Almost the entire events of the novella consist of what’s going on in his head.

First person narrators tend to create a strong relationship with the reader, and many authors exploit this attraction to make the narrator persuasive or acceptable. The important thing to keep in mind is that the narrator does not necessarily represent the author’s own personal opinions.

Sometimes the author may act as the first person narrator, or make little attempt to create a fictional constructed character. But readers should never assume that narrators are a direct reflection of the author’s own opinions.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. The book was written by the author of these web page guidance notes.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. The book was written by the author of these web page guidance notes.

Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon US

Third person narrators

This is the most traditional manner of delivering narratives, in which the author creates a distance between author, character, and reader.

John Belstaff was a gentleman farmer who had lived at Aylesbury Reach ever since inheriting the property from his father twenty years previously. He had worked the land to profitable advantage during that time, and was now looking forward to a peaceful retirement.

All the information we have about such a character is presented to us by the author, and there is no intervening narrator. This gives the author an opportunity to create multiple characters in a single narrative, and to show events from their different points of view. If the author chooses to reveal the innermost thoughts and feelings of any characters, this approach is known as omniscient narrative mode.

Jane Austen uses a third person narrative mode for her novel Pride and Pejudice (1813). But part its charm is the ironic and witty authorial observations she scatters through the narrative.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

Omniscient narrators

The term omniscient means ‘all-knowing’ or ‘all-seing’. It comes from the language of religion, and in this sense the author is presenting a God-like view of events in which the characters’ innermost thoughts, feelings, and aspirations are revealed.

Authors are at liberty to tell us as much or as little about their characters as they wish, but once they have chosen an omniscient mode of narration they cannot claim ignorance about any aspect of their story. Having said that, many of them sometimes do – in order to create the impression of honesty or an ordinary human intelligence at work.

Unreliable narrators

Many modern writers have created what are called unreliable narrators. In this case a story is told in the first person mode by a narrator who has flawed perceptions, a limited understanding of events, or who maybe even tells lies. In such cases the reader is given the additional task of unravelling the ‘true’ story from information some parts of which are misleading.

A very famous case in point is Henry James’ ghost story The Turn of the Screw (1898). In this a governess to two children in a large country house provides a dramatic account of how they have been demonically possessed by the spirits of former servants who are now dead. The story has become famous because it can be interpreted in a number of different ways. The governess does not provide any evidence to support the claims she makes, and she invents scenes which nobody else in the story observes. However, the reader only has her account from which to make any sense of what is actually happening. It is only by comparing small details of her account that we can see that she is an unreliable narrator.

A very famous case in point is Henry James’ ghost story The Turn of the Screw (1898). In this a governess to two children in a large country house provides a dramatic account of how they have been demonically possessed by the spirits of former servants who are now dead. The story has become famous because it can be interpreted in a number of different ways. The governess does not provide any evidence to support the claims she makes, and she invents scenes which nobody else in the story observes. However, the reader only has her account from which to make any sense of what is actually happening. It is only by comparing small details of her account that we can see that she is an unreliable narrator.

In fact this story has both a first person outer narrator, and an inner narrator who reads a copy of the written account of events created by the governess herself – making it an extremely complex thread to unravel.

Another (very amusing) example is Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Pale Fire (1962) in which his first person narrator Charles Kinbote edits a long poem in four cantos composed by an American writer who was his campus neighbour. On the surface, the poem is composed of scenes from the poet’s life and his philosophic reflections on domestic relationships.

But in a series of extended footnotes Kinbote analyses the poem in detail for hidden meanings. He reveals that it contains a subtly coded account of Kinbote’s own life, and his dramatic escape from eastern Europe which he had privately related to the poet as part of their friendship. Since the poet is dead, we only have Kinbote’s own word for the truth in any of his claims. However, Nabokov provides the reader with enough information to work out that Kinbote is a madman, and all his interpretations and literary detective work is a pack of lies.

The framed narrative

Many stories begin with a first or third person narrator who establishes the circumstances by which the story is known, In other words, somebody (named or un-named) informs the reader how the details of the story have come into being. The scene is set, or some prefatory knowledge is imparted. This takes the form of an introduction.

Then the main substance of the story is related, which constitutes the bulk of the narrative. This may be presented by the opening narrator, or it might be information from a different source – a second narrator, or a story passed on via letters or a diary from someone else.

At the end of the narrative, there is usually a return to the first narrator, who might reflect on the substance of what has been revealed. This is the ‘conclusion’ or the closing part of the overall narrative.

Such a case is called a framed narrative. An outer narrator passes the storytelling over to an inner narrator who relates the bulk of events.

A famous and much-discussed example is Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1898). The story begins on board a ship moored in the Thames estuary, where a group of experienced seamen are reminiscing about their maritime experiences. An un-named outer narrator sets the scene, and then introduces Captain Marlow, who regales the company with the story of a journey he once made into the interior of Africa.

A famous and much-discussed example is Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1898). The story begins on board a ship moored in the Thames estuary, where a group of experienced seamen are reminiscing about their maritime experiences. An un-named outer narrator sets the scene, and then introduces Captain Marlow, who regales the company with the story of a journey he once made into the interior of Africa.

As readers we tend to forget all about the outer narrator, and even that the main events of the story are being spoken by Marlow. But at the end, when Marlow has finished his tale, the outer narrator comes back onto the page to ‘remind’ us that we are still on a ship in the Thames. The main narrative of a journey up an African river is ‘framed’ by the setting on the Thames, and the reader is implicitly being invited to draw parallels between the two.

© Roy Johnson 2012

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

Does this mean that dictionaries in the form of printed books are obsolete? I think not – because for most people it’s still more convenient to reach a book off the shelf to solve a problem or look up a definition. And that’s quite apart from the secondary pleasure of reference books – making those serendipitous discoveries on adjacent pages.

Does this mean that dictionaries in the form of printed books are obsolete? I think not – because for most people it’s still more convenient to reach a book off the shelf to solve a problem or look up a definition. And that’s quite apart from the secondary pleasure of reference books – making those serendipitous discoveries on adjacent pages.