tutorial, characters, resources, video, further reading

A Room with a View (1905) is a comedy of manners and a satirical critique of English stuffiness and hypocrisy. Lucy Honeychurch must choose between cultured but emotionally frozen Cecil Vyse and the impulsive George Emerson. The Surrey stockbroker belt is contrasted with the magic of Florence, where she eventually ends up on her honeymoon. Upper middle-class English tourists in Italy are an easy target for Forster in some very amusing scenes.

E.M.Forster

E.M. Forster is a bridge between the nineteenth and the twentieth century novel. He documents the Edwardian and Georgian periods in a witty and elegant prose, satirising the middle and upper classes he knew so well. He was a friend of Virginia Woolf, with whom he worked out some of the ground rules of literary modernism. These included the concept of ‘tea-tabling’ – making the substance of serious fiction the ordinary events of everyday life. He was also a member of The Bloomsbury Group.

His novels grew in complexity and depth, until he eventually gave up fiction in 1923. This was because he no longer felt he could write about the subject of heterosexual love which he did not know or feel. Instead, he turned to essays – which are well worth reading.

A Room with a View – plot summary

Lucy Honeychurch, a young upper middle class woman, visits Italy under the charge of her older cousin Charlotte. At their guesthouse, in Florence, they are given rooms that look into the courtyard rather than out over the river Arno. Mr. Emerson, a fellow guest, generously offers them the rooms belonging to himself and his son George. Lucy is an avid young pianist. Mr. Beebe an English clergyman guest, watches her passionate playing and predicts that someday she will live her life with as much gusto as she plays the piano.

Lucy Honeychurch, a young upper middle class woman, visits Italy under the charge of her older cousin Charlotte. At their guesthouse, in Florence, they are given rooms that look into the courtyard rather than out over the river Arno. Mr. Emerson, a fellow guest, generously offers them the rooms belonging to himself and his son George. Lucy is an avid young pianist. Mr. Beebe an English clergyman guest, watches her passionate playing and predicts that someday she will live her life with as much gusto as she plays the piano.

Lucy’s visit to Italy is marked by several significant encounters with the Emersons. George explains that his father means well, but always offends everyone. Mr. Emerson tells Lucy that his son needs her in order to overcome his youthful melancholy. Later, Lucy comes in close contact with two quarreling Italian men. One man stabs the other, and she faints, to be rescued (and kissed) by George.

On a country outing in the hills, Lucy again encounters George, who is standing on a terrace covered with blue violets. George kisses her again, but this time Charlotte sees him and chastises him and leaves with Lucy for Rome the next day.

The second half of the book centers on Lucy’s home in Surrey, where she lives with her mother and her brother, Freddy. A man she met in Rome, the snobbish Cecil Vyse, proposes marriage to her for the third time, and she accepts him. He disapproves of her family and the country people she knows. There is a small, ugly villa available for rent in the town, and as a joke, Cecil offers it to the Emersons, whom he meets by chance in a museum. They take him up on the offer and move in, much to Lucy’s initial horror.

George plays tennis with the Honeychurches on a Sunday when Cecil is at his most intolerable. Cecil reads from a book by Miss Lavish, a woman who also stayed with Lucy and Charlotte in Florence. The novel records a kiss among violets, so Lucy realizes that Charlotte let the secret out. In a moment alone, George kisses her again. Lucy tells him to leave, but George insists that Cecil is not the right man for her. Lucy sees Cecil in a new light, and breaks off her engagement that night.

However, Lucy will not believe that she loves George; she wants to stay unmarried and travel to Greece with some elderly women she met in Italy. She meets old Mr. Emerson by chance, who insists that she loves George and should marry him, because it is what her soul truly wants. Lucy realizes he is right, and though she must fly against convention, she marries George, and the book ends with the happy couple staying together in the Florence pension again, in a room with a view.

Study resources

![]() A Room with a View – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

A Room with a View – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() A Room with a View – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

A Room with a View – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() A Room with a View – unabridged classics Audio CD – Amazon UK

A Room with a View – unabridged classics Audio CD – Amazon UK

![]() A Room with a View – BBC audio books edition – Amazon UK

A Room with a View – BBC audio books edition – Amazon UK

![]() A Room with a View – Merchant-Ivory film on VHS – Amazon UK

A Room with a View – Merchant-Ivory film on VHS – Amazon UK

![]() A Room with a View – eBook version at Project Gutenberg

A Room with a View – eBook version at Project Gutenberg

![]() A Room with a View – audioBook version at LibriVox

A Room with a View – audioBook version at LibriVox

![]() The Cambridge Companion to E.M.Forster – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to E.M.Forster – Amazon UK

![]() E.M.Forster at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

E.M.Forster at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() E.M.Forster at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

E.M.Forster at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Principal characters

| Lucy Honeychurch | a musical and spirited girl |

| Mrs Honeychurch | her mother, a widow |

| Freddy | her brother |

| Charlotte Bartlett | Lucy’s older, poorer cousin and an old maid |

| Mr Emerson | a liberal, plain-speaking widower |

| George Emerson | his truth-seeking son |

| Cecil Vyse | an over-cultivated snob |

| Mr Beebe | the rector in Lucy’s home town |

| Miss Lavish | lady novelist with strident, commonplace views |

| Mr Eager | self-righteous British chaplain in Florence |

A Room with a View – film version

Merchant-Ivory 1985 film adaptation

This is a production which takes one or two minor liberties with the original novel. But it’s beautifully acted, with the deliciously pouting Helena Bonham Carter as the heroine Lucy, plus Denholm Eliot as Mr Emerson, Daniel Day-Lewis as a wonderfully pompous Cecil Vyse, and Maggie Smith as the poisonous hanger-on Charlotte. The settings are delightfully poised between Florentine Italy and the home counties stockbroker belt. I’ve watched it several times, and it never ceases to be visually elegant and emotionally well observed. This film was nominated for eight Academy awards when it appeared, and put the Merchant-Ivory team on the cultural map.

![]() See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

See reviews of the film at the Internet Movie Database

Further reading

![]() David Bradshaw, The Cambridge Companion to E.M. Forster, Cambridge University Press, 2007

David Bradshaw, The Cambridge Companion to E.M. Forster, Cambridge University Press, 2007

![]() Richard Canning, Brief Lives: E.M. Forster, London: Hesperus Press, 2009

Richard Canning, Brief Lives: E.M. Forster, London: Hesperus Press, 2009

![]() G.K. Das and John Beer, E. M. Forster: A Human Exploration, Centenary Essays, New York: New York University Press, 1979.

G.K. Das and John Beer, E. M. Forster: A Human Exploration, Centenary Essays, New York: New York University Press, 1979.

![]() Mike Edwards, E.M. Forster: The Novels, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001

Mike Edwards, E.M. Forster: The Novels, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001

![]() E.M. Forster, Aspects of the Novel, London: Penguin Classics, 2005

E.M. Forster, Aspects of the Novel, London: Penguin Classics, 2005

![]() P.N. Furbank, E.M. Forster: A Life, Manner Books, 1994

P.N. Furbank, E.M. Forster: A Life, Manner Books, 1994

![]() Frank Kermode, Concerning E.M. Forsterl, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2009

Frank Kermode, Concerning E.M. Forsterl, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2009

![]() Rose Macaulay, The Writings of E. M. Forster, New York: Barnes and Noble, 1970.

Rose Macaulay, The Writings of E. M. Forster, New York: Barnes and Noble, 1970.

![]() Nigel Messenger, How to Study an E.M. Forster Novel, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991

Nigel Messenger, How to Study an E.M. Forster Novel, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991

![]() Wendy Moffatt, E.M. Forster: A New Life, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010

Wendy Moffatt, E.M. Forster: A New Life, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010

![]() Nicolas Royle, E.M. Forster (Writers and Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1999

Nicolas Royle, E.M. Forster (Writers and Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1999

![]() Jeremy Tambling (ed), E.M. Forster: Contemporary Critical Essays, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995

Jeremy Tambling (ed), E.M. Forster: Contemporary Critical Essays, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995

A Room with a View – film interview

Daniel Day Lewis on Cecil Vyse

Other works by E.M. Forster

Where Angels Fear to Tread (1902) is Forster’s first novel and a very witty debut. A spirited middle-class English girl goes to Italy and becomes involved with a local man. The English family send out a party to ‘rescue’ her (shades of Henry James) – but they are too late; she has already married him. But when a baby is born, the family returns with renewed hostility. The clash between Mediterranean living spirit and deadly English rectitude is played out with amusing and tragic consequences.

Where Angels Fear to Tread (1902) is Forster’s first novel and a very witty debut. A spirited middle-class English girl goes to Italy and becomes involved with a local man. The English family send out a party to ‘rescue’ her (shades of Henry James) – but they are too late; she has already married him. But when a baby is born, the family returns with renewed hostility. The clash between Mediterranean living spirit and deadly English rectitude is played out with amusing and tragic consequences.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Howards End (1910) is a State of England novel, and possibly Forster’s greatest work – though that’s just my opinion. Two families are contrasted: the intellectual and cultivated Schlegels, and the capitalist Wilcoxes. A marriage between the two leads to spiritual rivalry over the possession of property. Following on their social coat tails is a working-class would-be intellectual who is caught between two conflicting worlds. The outcome is a mixture of tragedy and resignation, leavened by hope for the future in the young and free-spirited.

Howards End (1910) is a State of England novel, and possibly Forster’s greatest work – though that’s just my opinion. Two families are contrasted: the intellectual and cultivated Schlegels, and the capitalist Wilcoxes. A marriage between the two leads to spiritual rivalry over the possession of property. Following on their social coat tails is a working-class would-be intellectual who is caught between two conflicting worlds. The outcome is a mixture of tragedy and resignation, leavened by hope for the future in the young and free-spirited.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended.

E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended.

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on E.M. Forster

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes

Gustav von Aschenbach is a famous author in his early fifties. He is a widower, dedicated to his art, and disciplined to the point of severity. While strolling outside a cemetery in his native Munich he has a disturbing encounter with a red-haired man, after which he resolves to take a trip. He reserves a suite in the Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Lido island of Venice. While en route to the island by vaporetto, he sees an elderly man with a wig, false teeth, makeup, and foppish attire, which disgusts him. Soon afterwards he has a disturbing encounter with a gondolier.

Gustav von Aschenbach is a famous author in his early fifties. He is a widower, dedicated to his art, and disciplined to the point of severity. While strolling outside a cemetery in his native Munich he has a disturbing encounter with a red-haired man, after which he resolves to take a trip. He reserves a suite in the Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Lido island of Venice. While en route to the island by vaporetto, he sees an elderly man with a wig, false teeth, makeup, and foppish attire, which disgusts him. Soon afterwards he has a disturbing encounter with a gondolier.

Thomas Mann: a life This exploration of Thomas Mann’s life by Donald Prater describes his relationship of intense rivalry with his brother Heinrich, who was also a novelist, his (much-concealed) homosexuality, his career as a prolific essayist, and the vast achievement of his novels. Particular attention is paid to Mann’s opposition to Nazism, and his role in the rise and fall of Hitlerism. It traces Mann’s political development from the nationalistic conservatism of his younger days, to the humanistic anti-Nazim of his maturity.

Thomas Mann: a life This exploration of Thomas Mann’s life by Donald Prater describes his relationship of intense rivalry with his brother Heinrich, who was also a novelist, his (much-concealed) homosexuality, his career as a prolific essayist, and the vast achievement of his novels. Particular attention is paid to Mann’s opposition to Nazism, and his role in the rise and fall of Hitlerism. It traces Mann’s political development from the nationalistic conservatism of his younger days, to the humanistic anti-Nazim of his maturity.  Mario and the Magician

Mario and the Magician The Magic Mountain

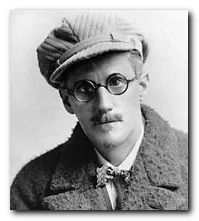

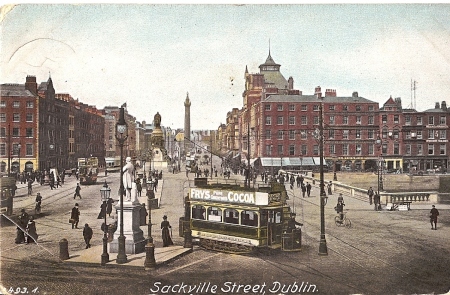

The Magic Mountain This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century, ending with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. The book caused controversy when it first appeared, and was banned in Ireland almost immediately upon publication, the first of many of Joyce’s works to be censored or banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories.

This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century, ending with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. The book caused controversy when it first appeared, and was banned in Ireland almost immediately upon publication, the first of many of Joyce’s works to be censored or banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return. Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day. The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

During Christmas dinner, whilst Pip is scared that someone will notice the missing pie. Police officers arrive and hunt through the marshes outside the village for escaped convicts. They accost the man helped by Pip, but when questioned about where he got the food and file, he claims he stole the items himself. The police take him off to the Hulk, a giant prison ship.

During Christmas dinner, whilst Pip is scared that someone will notice the missing pie. Police officers arrive and hunt through the marshes outside the village for escaped convicts. They accost the man helped by Pip, but when questioned about where he got the food and file, he claims he stole the items himself. The police take him off to the Hulk, a giant prison ship.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory. Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

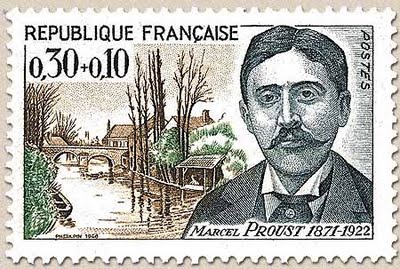

The Cambridge Companion to Proust

The Cambridge Companion to Proust Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp, pretending that Charlotte is ill and in a hospital. He takes Lolita to a hotel, where he meets a strange man (later revealed to be Clare Quilty), who seems to know who he is. Humbert attempts to use sleeping pills on Lolita so that he may molest her without her knowledge, but they have little effect on her. Instead, she consciously seduces Humbert the next morning. He discovers that he is not her first lover, as she had sex with a boy at summer camp. Humbert reveals to Lolita that Charlotte is actually dead; Lolita has no choice but to accept her stepfather into her life on his terms.

Humbert picks Lolita up from camp, pretending that Charlotte is ill and in a hospital. He takes Lolita to a hotel, where he meets a strange man (later revealed to be Clare Quilty), who seems to know who he is. Humbert attempts to use sleeping pills on Lolita so that he may molest her without her knowledge, but they have little effect on her. Instead, she consciously seduces Humbert the next morning. He discovers that he is not her first lover, as she had sex with a boy at summer camp. Humbert reveals to Lolita that Charlotte is actually dead; Lolita has no choice but to accept her stepfather into her life on his terms. One day in 1952, Humbert receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is married, pregnant, and in desperate need of money. Humbert goes to see Lolita, giving her money and hoping to kill the man who abducted her. She reveals the truth: Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte’s and the writer of the school play, checked her out of the hospital and attempted to make her star in one of his pornographic films; when she refused, he threw her out.

One day in 1952, Humbert receives a letter from Lolita, now 17, who tells him that she is married, pregnant, and in desperate need of money. Humbert goes to see Lolita, giving her money and hoping to kill the man who abducted her. She reveals the truth: Clare Quilty, an acquaintance of Charlotte’s and the writer of the school play, checked her out of the hospital and attempted to make her star in one of his pornographic films; when she refused, he threw her out.

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

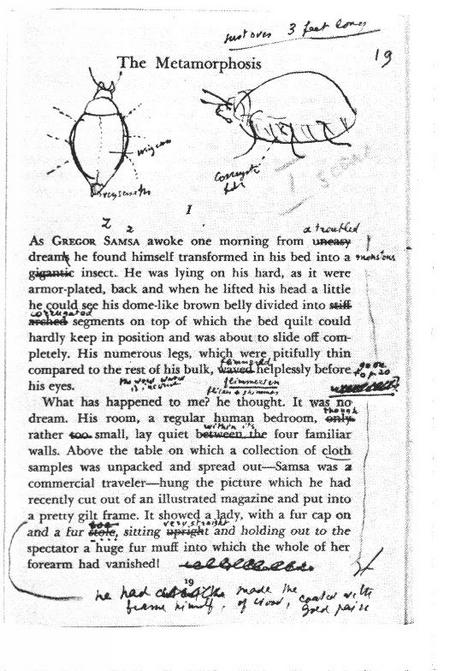

When Gregor’s supervisor arrives at the house and demands Gregor come out of his room, Gregor manages to roll out of bed and unlock his door. His appearance horrifies his family and supervisor; his supervisor flees while his family chases him back into his room.

When Gregor’s supervisor arrives at the house and demands Gregor come out of his room, Gregor manages to roll out of bed and unlock his door. His appearance horrifies his family and supervisor; his supervisor flees while his family chases him back into his room. Later, his parents take in lodgers and use Gregor’s room as a dumping area for unwanted objects. Gregor becomes dirty, covered in dust and old bits of rotten food. One day, Gregor hears Grete playing her violin to entertain the lodgers. Gregor is attracted to the music, and slowly walks into the dining room despite himself, entertaining a fantasy of getting his beloved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. The lodgers see him and give notice, refusing to pay the rent they owe, even threatening to sue the family for harboring him while they stayed there. Grete determines that the monstrous vermin is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. She suggests that they must get rid of it. Gregor retreats to his room and collapses, finally succumbing to his wound, and dying alone.

Later, his parents take in lodgers and use Gregor’s room as a dumping area for unwanted objects. Gregor becomes dirty, covered in dust and old bits of rotten food. One day, Gregor hears Grete playing her violin to entertain the lodgers. Gregor is attracted to the music, and slowly walks into the dining room despite himself, entertaining a fantasy of getting his beloved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. The lodgers see him and give notice, refusing to pay the rent they owe, even threatening to sue the family for harboring him while they stayed there. Grete determines that the monstrous vermin is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. She suggests that they must get rid of it. Gregor retreats to his room and collapses, finally succumbing to his wound, and dying alone. Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

The Trial

The Trial Amerika

Amerika

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.