tutorial, characters, criticism, video, study resources

The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886) is probably Hardy’s greatest work – a novel whose aspirations are matched by artistic shaping and control. It is the tragic history of Michael Henchard – a man who rises to civic prominence, but whose past comes back to haunt him. This is not surprising, because he sells his wife in the opening chapter. When she comes back unexpectedly, he is trapped between present and past.

Thomas Hardy

He is also locked into a psychological contest with an alter-ego figure with whom he battles both metaphorically and realistically. Henchard falls in the course of the novel from civic honour and commercial greatness into a tragic figure, a man defeated by his own strengths as much as his weaknesses. There are strong echoes of King Lear here, and some of the most powerfully dramatic and psychologically revealing scenes in all of Hardy’s work.

Hardy is one of the few writers (Lawrence was another) who made a significant contribution to English literature in the form of the novel, poetry, and the short story. His writing is full of delightful effects, beautiful images and striking language.

He creates unforgettable characters and orchestrates stories which pull at your heart strings. It has to be said that he also relies on coincidences and improbabilities of plot which (though common in the nineteenth century) some people see as weaknesses. However, his sense of drama, his powerful language, and his wonderful depiction of the English countryside make him an enduring favourite.

The Mayor of Casterbridge – plot summary

At a country fair near Casterbridge, a young hay-trusser named Michael Henchard gets drunk and quarrels with his wife, Susan. He then auctions off his wife and baby daughter, Elizabeth-Jane, to a sailor, Mr. Newson, for five guineas. Remorseful at his stupidity and loss, he next day swears not to touch liquor again for as many years as he has lived so far (twenty-one). Nineteen years later, Henchard, now a successful grain merchant, has become Mayor of Casterbridge, known for his staunch sobriety. He is well respected for his financial acumen and his work ethic, but he is not well liked. Impulsive, selfish behaviour and a violent temper are still part of his character.

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

When Henchard returns to Casterbridge he leaves Lucetta to face the social consequences of their fling. Yet just as Henchard is about to send for Lucetta, Susan unexpectedly appears in Casterbridge with her daughter, Elizabeth-Jane, who is now fully grown. Susan and Elizabeth-Jane are both very poor. Newson appears to have been lost at sea.

Just as Susan and Elizabeth-Jane arrive, so does an amiable Scotsman, Donald Farfrae, who has experience as a grain and corn merchant, and is on the cutting edge of agricultural science. He befriends Henchard and helps him out of a bad financial situation by giving him some timely advice. Henchard persuades him to stay and offers him a job as his corn factor. He also makes Farfrae a close friend and confides in him about his past history and personal life.

Henchard is also reunited with Susan and the fully grown Elizabeth-Jane, setting them up in a nearby house. He pretends to court Susan, and marries her. Both Henchard and Susan keep their past history from their daughter. Henchard also keeps Lucetta a secret. He writes to her, informing her that their marriage is off. Lucetta is devastated and asks for the return of her letters. Henchard attempts to return them, but Lucetta misses the appointment.

The new state of affairs sets in motion a decline in Henchard’s fortunes. His relationship with Farfrae deteriorates gradually as Farfrae becomes more popular than Henchard. In addition to being more friendly and amiable, Farfrae is better informed, better educated, and everything Henchard himself wants to be. Henchard feels threatened by Farfrae, particularly when Elizabeth-Jane starts to fall in love with him.

The competition between Donald Farfrae and Henchard grows. Eventually they part company and Farfrae sets himself up as an independent hay and corn merchant. Henchard meanwhile makes increasingly aggressive, risky business decisions that put him in financial danger. The business rivalry leads to Henchard standing in the way of a marriage between Farfrae and Elizabeth-Jane.

At this point Susan dies and Henchard learns he is not Elizabeth-Jane’s father: she is Newson’s daughter. Feeling ashamed and hard done by, Henchard conceals the secret from Elizabeth-Jane, but grows cold and cruel towards her.

In the meantime, Henchard’s former mistress, Lucetta, arrives from Jersey and purchases a house in Casterbridge. She has inherited money from a wealthy relative. Initially she wants to pick up her relationship with him where it left off. She takes Elizabeth-Jane into her household as a companion thinking it will give Henchard an excuse to come visit, but the plan backfires.

The details of how Henchard sold his first wife become public knowledge when a man who witnessed the sale makes the story public. Henchard does not deny the story, but when Lucetta hears a little bit more about what kind of man Henchard really is she no longer particularly likes what she sees.

Donald Farfrae, who visits Lucetta’s house to see Elizabeth-Jane, now becomes completely distracted by Lucetta, having no idea that Lucetta is the mysterious woman who was informally engaged to Henchard.

Henchard, although he was initially reluctant, now gradually realizes that he wants to marry Lucetta, particularly since he’s having financial trouble due to some speculations having gone bad.

He bullies Lucetta into agreeing to marry him – but by this point she is in love with Farfrae. The two run away one weekend and get married. Henchard’s credit collapses, he becomes bankrupt, and he sells all his personal possessions to pay creditors.

As Henchard’s fortunes decline, Farfrae’s rise. He buys Henchard’s old business and employs Henchard as a journeyman day-laborer. Farfrae is always trying to help the man who helped him get started, whom he still regards as a friend and a former mentor. He does not realize Henchard is his enemy even though the town council and Elizabeth-Jane both warn him.

Lucetta, feeling safe and comfortable in her marriage with Farfrae, keeps her former relationship with Henchard a secret. But this secret is revealed and the townspeople publicly shame Henchard and Lucetta. Lucetta, who by this point is pregnant, dies of an epileptic seizure.

Suddenly Newson, Elizabeth-Jane’s biological father, returns. Henchard is afraid of losing her companionship and tells Newson she is dead. Henchard is once again impoverished, and as soon as the twenty-first year of his oath is up, he starts drinking again. By the time Elizabeth-Jane, who months later is married to Donald Farfrae and reunited with Newson, goes looking for Henchard to forgive him, he has died and left a will requesting no funeral and that no man should remember him.

Study resources

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

The Mayor of Casterbridge – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

The Mayor of Casterbridge – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Mayor of Casterbridge – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Mayor of Casterbridge – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

The Mayor of Casterbridge – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

The Mayor of Casterbridge – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – Everyman Library Classics – Amazon UK

The Mayor of Casterbridge – Everyman Library Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – Everyman Library Classics – Amazon US

The Mayor of Casterbridge – Everyman Library Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – York Notes – Amazon UK

The Mayor of Casterbridge – York Notes – Amazon UK

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – Cliffs Notes – Amazon UK

The Mayor of Casterbridge – Cliffs Notes – Amazon UK

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – 1978 BBC TV version on DVD – Amaz UK

The Mayor of Casterbridge – 1978 BBC TV version on DVD – Amaz UK

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – 2003 BBC TV version on DVD – Amaz UK

The Mayor of Casterbridge – 2003 BBC TV version on DVD – Amaz UK

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – CD-ROM and audio pack – Amazon UK

The Mayor of Casterbridge – CD-ROM and audio pack – Amazon UK

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – audioBook version at LibriVox

The Mayor of Casterbridge – audioBook version at LibriVox

![]() The Mayor of Casterbridge – eBook versions at Gutenberg

The Mayor of Casterbridge – eBook versions at Gutenberg

![]() Thomas Hardy: A Biography – definitive study – Amazon UK

Thomas Hardy: A Biography – definitive study – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Thomas Hardy’s Complete Fiction – Kindle eBook

Thomas Hardy’s Complete Fiction – Kindle eBook

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

Principal characters

| Michael Henchard | the Mayor of Casterbridge, a corn-dealer |

| Susan | his wife, who he sells at auction |

| Elizabeth-Jane | their daughter, who dies in infancy |

| Richard Newson | a sailor who ‘buys’ Henchard’s wife |

| Elizabeth-Jane | Susan’s second daughter, with Richard Newsom |

| Donald Farfrae | a scientific corn merchant, who also becomes the Mayor of Casterbridge |

| Lucette Le Sueur | French-speaking woman from Jersey |

Film version

opening of 2003 BBC TV version

music by Adrian Johnston

Further reading

![]() J.O. Bailey, The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: A Handbook and Commentary, Chapel Hill:N.C., 1970.

J.O. Bailey, The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: A Handbook and Commentary, Chapel Hill:N.C., 1970.

![]() John Bayley, An Essay on Hardy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

John Bayley, An Essay on Hardy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Penny Boumelha, Thomas Hardy and Women: Sexual Ideology and Narrative Form, Brighton: Harvester, 1982.

Penny Boumelha, Thomas Hardy and Women: Sexual Ideology and Narrative Form, Brighton: Harvester, 1982.

![]() Kristin Brady, The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1982.

Kristin Brady, The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1982.

![]() L. St.J. Butler, Alternative Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1989.

L. St.J. Butler, Alternative Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1989.

![]() Raymond Chapman, The Language of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1990.

Raymond Chapman, The Language of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1990.

![]() R.G.Cox, Thomas Hardy: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

R.G.Cox, Thomas Hardy: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

![]() Ralph W.V. Elliot, Thomas Hardy’s English, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984.

Ralph W.V. Elliot, Thomas Hardy’s English, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984.

![]() Simon Gattrel, Hardy the Creator: A Textual Biography, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

Simon Gattrel, Hardy the Creator: A Textual Biography, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

![]() James Gibson (ed), The Complete Poems of Thomas Hardy, London, 1976.

James Gibson (ed), The Complete Poems of Thomas Hardy, London, 1976.

![]() I. Gregor, The Great Web: The Form of Hardy’s Major Fiction, London: Faber, 1974.

I. Gregor, The Great Web: The Form of Hardy’s Major Fiction, London: Faber, 1974.

![]() Florence Emily Hardy, The Life of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1962. (This is more or less Hardy’ s autobiography, since he told his wife what to write.)

Florence Emily Hardy, The Life of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1962. (This is more or less Hardy’ s autobiography, since he told his wife what to write.)

![]() P. Ingham, Thomas Hardy: A Feminist Reading, Brighton: Harvester, 1989.

P. Ingham, Thomas Hardy: A Feminist Reading, Brighton: Harvester, 1989.

![]() P.Ingham, The Language of Class and Gender: Transformation in the English Novel, London: Routledge, 1995,

P.Ingham, The Language of Class and Gender: Transformation in the English Novel, London: Routledge, 1995,

![]() D. Kramer, Thomas Hardy: The Forms of Tragedy, London: Macmillan, 1975.

D. Kramer, Thomas Hardy: The Forms of Tragedy, London: Macmillan, 1975.

![]() J. Hillis Miller, Thomas Hardy: Distance and Desire, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970.

J. Hillis Miller, Thomas Hardy: Distance and Desire, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970.

![]() Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, London: Bodley Head, 1971.

Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, London: Bodley Head, 1971.

![]() Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006. (This is the definitive biography.)

Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006. (This is the definitive biography.)

![]() Michael Millgate and Richard L. Purdy (eds), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978-

Michael Millgate and Richard L. Purdy (eds), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978-

![]() R. Morgan, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

R. Morgan, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

![]() Harold Orel (ed), Thomas Hardy’s Personal Writings, London, 1967.

Harold Orel (ed), Thomas Hardy’s Personal Writings, London, 1967.

![]() Norman Page, Thomas Hardy: The Novels, London: Macmillan, 2001.

Norman Page, Thomas Hardy: The Novels, London: Macmillan, 2001.

![]() F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Companion, London: Macmillan, 1968.

F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Companion, London: Macmillan, 1968.

![]() F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Dictionary, New York: New York University Press, 1989.

F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Dictionary, New York: New York University Press, 1989.

![]() Richard L. Purdy, Thomas Hardy: A Bibliographical Study, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978.

Richard L. Purdy, Thomas Hardy: A Bibliographical Study, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978.

![]() Marlene Springer, Hardy’s Use of Allusion, London: Macmillan, 1983.

Marlene Springer, Hardy’s Use of Allusion, London: Macmillan, 1983.

![]() Rosemary Sumner, Thomas Hardy: Psychological Novelist, London: Macmillan, 1981.

Rosemary Sumner, Thomas Hardy: Psychological Novelist, London: Macmillan, 1981.

![]() Richard H. Taylor, The Neglected Hardy: Thomas Hardy’s Lesser Novels, London: Macmillan, 1982.

Richard H. Taylor, The Neglected Hardy: Thomas Hardy’s Lesser Novels, London: Macmillan, 1982.

![]() Richard H. Taylor, The Personal Notebooks of Thomas Hardy, London, 1978.

Richard H. Taylor, The Personal Notebooks of Thomas Hardy, London, 1978.

![]() Merryn Williams, A Preface to Hardy, London: Longman, 1976.

Merryn Williams, A Preface to Hardy, London: Longman, 1976.

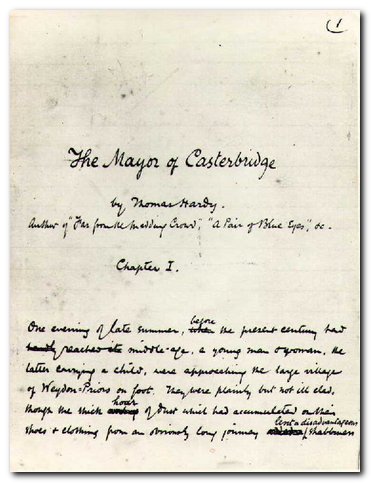

Manuscript of The Mayor of Casterbridge

Other works by Thomas Hardy

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Jude the Obscure is Hardy’s last major statement before he gave up writing novels for good. Hero Jude is intellectually ambitious but held back by his work as stonemason and his dalliance with earthy Arabella. When he meets his spiritual soulmate Sue Brideshead, everything seems set fair for success – except that she is capricious and sexually repressed. Jude struggles to do the right thing – but the Fates are against him. The outcome is heart-rendingly bleak and tragic. This novel reveals the deep-seated social and sexual tensions in Hardy – himself a self-made man from a humble background.

Jude the Obscure is Hardy’s last major statement before he gave up writing novels for good. Hero Jude is intellectually ambitious but held back by his work as stonemason and his dalliance with earthy Arabella. When he meets his spiritual soulmate Sue Brideshead, everything seems set fair for success – except that she is capricious and sexually repressed. Jude struggles to do the right thing – but the Fates are against him. The outcome is heart-rendingly bleak and tragic. This novel reveals the deep-seated social and sexual tensions in Hardy – himself a self-made man from a humble background.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Thomas Hardy – web links

![]() Thomas Hardy at Mantex

Thomas Hardy at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, book reviews. bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

![]() The Thomas Hardy Collection

The Thomas Hardy Collection

The complete novels, stories, and poetry – Kindle eBook single file download for £1.29 at Amazon.

![]() Thomas Hardy at Project Gutenberg

Thomas Hardy at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of digital formats.

![]() Thomas Hardy at Wikipedia

Thomas Hardy at Wikipedia

Biographical notes, social background, the novels and literary themes, poetry, religious beliefs and influence, biographies and criticism.

![]() The Thomas Hardy Society

The Thomas Hardy Society

Dorset-based site featuring educational activities, a biennial conference, a journal (three times a year) with links to the texts of all the major works.

![]() The Thomas Hardy Association

The Thomas Hardy Association

American-based site with photos and academic resources. Be prepared to search and drill down to reach the more useful materials.

![]() Thomas Hardy on the Internet Movie Database

Thomas Hardy on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors, actors, production features, box office, film reviews, and even quizzes.

![]() Thomas Hardy – online literary criticism

Thomas Hardy – online literary criticism

Small collection of academic papers and articles ‘favoring signed articles by recognized scholars and articles published in peer-reviewed sources’.

![]() Thomas Hardy’s Wessex

Thomas Hardy’s Wessex

Evolution of Wessex, contemporary reviews, maps, bibliography, links to other web sites, and history.

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on Thomas Hardy

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Part III. Their relationship comes to life again, and Sam proposes marriage to her for a second time. She accepts in principle, even though by doing so she would lose the home and the living Twycott has provided for her. But she needs time to break the news to her son. When she does so, he forbids her to marry Sam because the shame of it would downgrade him in the eyes of his friends. Sophy asks Sam to wait, and he does so for five years, after which he repeats his offer. Sophy renews her appeal to Randolph, who is now an undergraduate at Oxford. He forces her kneel down and swear that she will never marry Sam, claiming that he does this to honour the memory of his father. Five years later Sam has become a prosperous greengrocer. He stands in his shop doorway as Sophy’s funeral procession passes by on its way to her home village. Randolph who has now become a priest scowls at Sam from the mourner’s coach.

Part III. Their relationship comes to life again, and Sam proposes marriage to her for a second time. She accepts in principle, even though by doing so she would lose the home and the living Twycott has provided for her. But she needs time to break the news to her son. When she does so, he forbids her to marry Sam because the shame of it would downgrade him in the eyes of his friends. Sophy asks Sam to wait, and he does so for five years, after which he repeats his offer. Sophy renews her appeal to Randolph, who is now an undergraduate at Oxford. He forces her kneel down and swear that she will never marry Sam, claiming that he does this to honour the memory of his father. Five years later Sam has become a prosperous greengrocer. He stands in his shop doorway as Sophy’s funeral procession passes by on its way to her home village. Randolph who has now become a priest scowls at Sam from the mourner’s coach.

Chapter VIII. Grace visits Mrs Charmond in her gloomily placed house and makes a very good impression. Mrs Charmond invites her to be a traveling companion on her planned European tour. Meanwhile, Giles plants fir trees with Marty South.

Chapter VIII. Grace visits Mrs Charmond in her gloomily placed house and makes a very good impression. Mrs Charmond invites her to be a traveling companion on her planned European tour. Meanwhile, Giles plants fir trees with Marty South. his life and major writings

his life and major writings The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy Under the Greenwood Tree

Under the Greenwood Tree Far from the Madding Crowd

Far from the Madding Crowd The Return of the Native

The Return of the Native

Tess: DVD

Tess: DVD The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy