graphic design, interiors, objects and illustration

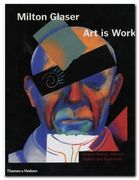

Don’t be put off by the cover design – this is a wonderful book. Milton Glaser is one of the most influential design and illustration gurus of the late 20th century in the USA. He was responsible for the “I love NY” logo and the poster of Bob Dylan with psychedelic hair which became a symbol of the 1980s. This is one of the few design books I have come across where the text is just as interesting as the graphics. Milton Glaser has thought a lot about the fundamentals of good design, and his ideas come through here via a series of interviews, plus his own commentary on the work illustrated.

And there’s a big bonus. He doesn’t just show his finished designs, but includes his preliminary drafts and early attempts which lead up to a successful outcome. So it’s like being invited to sit in his studio whilst he thinks and works out loud. He’s astonishingly versatile. The book contains examples of poster design, record covers, freehand drawings (amazingly similar to David Hockney in style) book illustrations, interior design, product design, typography, and publicity materials.

And there’s a big bonus. He doesn’t just show his finished designs, but includes his preliminary drafts and early attempts which lead up to a successful outcome. So it’s like being invited to sit in his studio whilst he thinks and works out loud. He’s astonishingly versatile. The book contains examples of poster design, record covers, freehand drawings (amazingly similar to David Hockney in style) book illustrations, interior design, product design, typography, and publicity materials.

His observations focus on the aesthetics of creativity – and yet he keeps his eye on the commercial and professional aspects of his work. He’s frank enough to admit that if the client’s budget is not big enough, he is prepared to discriminate between a ‘one hour’ idea and a ‘six hour’ design.

He’s a great believer in the idea that designers must continue to draw to develop their ideas, and he believes in creation as a form of work and process:

When you’re thinking you do a sketch and it’s fuzzy. You have to keep it fuzzy so that the brain looks at it and imagines another iteration that is clearer. Then you do another sketch that advances it again. It may take a number of these intermediate solutions before you arrive.

It’s a very instructive experience to see his rough sketches develop as he stretches and changes an idea until he comes up with what looks a fresh and spontaneous picture. That’s what he means by his book title. These designs do not just happen spontaneously: they are the result of hard work

He is very aware of modern painters – Klee, Mondrian, the much under-rated Sonia Delauney, Klimt, and Max Ernst. There’s also a portrait of Duke Ellington which has elements of Francis Bacon in its colouring and handling of paint, and a series of posters for the Venice Biennale which combine images of the city’s emblematic lion with ink spattering reflecting his appreciation of the work of Jackson Pollock

I found his book illustrations less successful, his restaurant designs inspired in terms of lighting, and his product design superb. There’s a whole page of sketches for a cocktail glass, any one of which you would be pleased to hold. But the finished product – complete with double-sided conical bowl with a vacuum to keep your Martini cold, fluted stem, and Art Deco collar uniting the two – well, my knees went weak when I turned the page, and I would pay substantial money to own a set.

© Roy Johnson 2003

Milton Glaser, Art is Work, London: Thames and Hudson, 2000, pp.272, ISBN 0500510288

More on art

More on media

More on design