tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

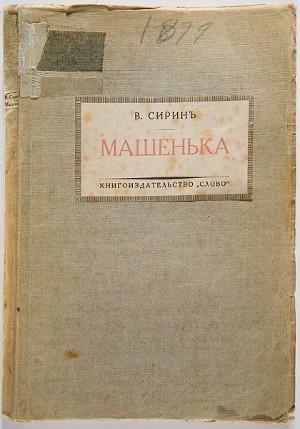

Mary (1926) is Vladimir Nabokov’s first novel. It was written in Berlin and appeared as Mashenka under his pen name of V. Sirin, which he used to distinguish himself from his father – a writer and politician who was also called Vladimir Nabokov.

The novel was completely ignored at the time of its first publication – and yet it is a marvellous debut, full of subtle touches and an admirable restraint in telling three stories simultaneously. It is the tale of a first young love, an account of political exile, and the evocation of a dawning poetic imagination.

It is also full of what were to become the hallmarks of Nabokov’s mature literary style – verbal playfulness, ironic twists of story line, the juxtaposition of tenderness with the grotesque, and beautiful evocations of the textures of everyday life.

Mary – critical commentary

The love story

At its most obvious and superficial level, this is a story about a youthful love affair. Ganin is a sensitive teenage boy living on a country estate in Russia at the time of the First World War. He sees a pretty girl at an outdoor musical event and falls in love with her.

In the idyllic summer days that follow they meet in the countryside. His later memories of youthful rapture and erotic exploration are mingled with his sense of freedom and appreciation of the natural world of which he feels himself a part. The whole of this experience is summoned from memory whilst he is in exile.

In the autumn Ganin and Mary both return to St Petersburg and find their opportunities for privacy are severely curtailed. There is a brief attempt at consummating their romance – but it fails. The relationship then dwindles as they are forced apart – yet Ganin keeps the memory of it alive as a significant event in his life.

When Ganin sees Mary’s photograph as the wife of the vulgarian Alfyorov, it re-awakens these memories and fuels him with the desire to recapture his first true love. He detaches himself from his current mistress Lyudmila, and ignores the attentions of Klara, his busty neighbour in the Berlin pension. He plans to intercept Mary when she arrives at the station. But when she finally reaches Berlin to join her husband, Ganin suddenly realises that his perfect experience with Mary is a thing of the past:

As Ganin looked up at the skeletal roof in the etherial sky he realised with merciless clarity that his affair with Mary was ended forever. It had lasted no more than four days – four days which were perhaps the happiest days of his life. But now he had exhausted his memories, was sated by them, and the image of Mary … remained in the house of ghosts, which itself was already a memory. Other than that image no Mary existed, nor could exist.

Nabokov’s great skill here is in evoking the delicious nature of an early romantic experience, recollected in a later and dramatically different period which spells its doom. It is significant that Mary is never dramatised: she is only summoned via Ganin’s memories of their time together. He cannot go back to his lost love, just as he will never go back to his homeland.

Memory and epiphany

Ganin is in exile. He has left behind his native Russia and like other exiles he been cut off from the emotional comforts of his birthplace. But he is maintaining a fragile intellectual stability by two means. The first is by keeping ‘the past’ alive with active efforts of reminiscence. The other is by an equally vigorous effort in appreciating the current pleasures of the material world in which he finds himself.

These moments of appreciation are fleeting experiences of aesthetic and sensory pleasure. He notices the shifting moods and textures of the world around him. Surrounded by vulgarity and desperation, he rescues from it precious moments of insight.

The trajectory of exile

At its deepest level the novel is about emigration and exile, and in one sense the imagined character of Mary, Ganin’s first true love, acts as a metaphor for the loss of homeland. Ganin has grown up in the idyllic world of an aristocratic Russian country estate for which he has very deep feelings. These are mingled with his feelings for the young girl Mary.

But he is separated from both by his participation in the Civil War which follows the revolution of 1917-18. When he is injured and on the losing side, he is forced to flee the country he loves in order to survive. Hence his temporary presence in the seedy pension in Berlin – the ‘first’ centre of emigration.

He is surrounded by the other flotsam and jetsam thrown up by political upheavals in his mother country: the old poet Podtyagin, the crapulous Alfronov, and two homosexual ballet dancers. Podtyagin is stranded without a visa, waiting to travel on to the ‘second’ centre of emigration – Paris. But it seems likely that he will die from heart failure before he makes the journey.

Ganin also feels as if he must move on – but he chooses what was to become the most celebrated route for exiles within a decade of the novel’s publication in 1926. This route was into southern France and the Mediterranean ports, from which it was possible to continue the journey westwards. In this sense Nabokov accurately prophesied his own future.

Like many other exiles from the Stalinist Soviet Union and Hitler’s Germany, Nabokov was forced to travel from Berlin in Germany then on to Paris in France, and finally to the Mediterranean coast. Hoping for safe transport to a neutral country such as Portugal, he eventually went to America. There is a very well-documented account of this escape route, much of which was organised by the American ‘special agent’ Varian Fry.

Double time-scheme

The narrative also takes place on two separate chronological planes at the same time. Events in the pension unfold between Monday and Saturday of a single week. Saturday is the day when Ganin has decided to leave Berlin, and it is the day when Mary is due to arrive.

But Ganin’s recollections of his youthful love affair and the country he has lost go back over the previous ten years. This period spans his summer romance with Mary, their return to Saint Petersburg, the end of his schooling, and his participation in the Civil War and its aftermath.

These two chrolologies are woven together quite seamlessly and present the reader with an unbroken narrative flow. This is a very skillful control of narrative in such a young writer, as Nabokov was at the time of the novel’s composition.

Mary – study resources

![]() Mary – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Mary – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Mary – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Mary – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Mashenka – Russian version – Amazon UK

Mashenka – Russian version – Amazon UK

![]() Mashenka – Russian version – Amazon US

Mashenka – Russian version – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Amazon UK

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years – Biography: Vol 1 – Amazon UK

Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years – Biography: Vol 1 – Amazon UK

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: American Years – Biography: Vol 2 – Amazon UK

Vladimir Nabokov: American Years – Biography: Vol 2 – Amazon UK

![]() Zembla – the official Nabokov web site

Zembla – the official Nabokov web site

![]() The Paris Review – Interview with Vladimir Nabokov

The Paris Review – Interview with Vladimir Nabokov

![]() Nabokov’s first English editions – Bob Nelson collection

Nabokov’s first English editions – Bob Nelson collection

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Mary – plot summary

1. Ganin is staying in a Russian-run boarding house in Berlin. A fellow guest Alfronov is expecting his wife to arrive from Russia.

2. Ganin is bored by his loveless affair with Lyudmila. He compares notes on life in exile with Alfronov.

3. An evocation of Berlin at night.

4. Ganin breaks off relations with Lyudmila, then wallows in the pleasure of reminiscences about Russia. He reconstructs the memory of recovering from typhus and forms the image of a girl. He reflects on the evanescence of even the most pleasant memories. Back at the pension he is caught by fellow guest Klara snooping in Alfronov’s desk, where he sees a photograph of his childhood sweetheart Mary, to whom Alfronov is now married.

5. Ganin and the old poet Podtyagin exchange reflections on memories.

6. Ganin recalls his first meeting with Mary and his first experiences of poetic epiphany.

7. He receives a letter from Lyudmila which he tears up and throws away without reading.

8. He lives in his memories of Russia and Mary, recalling their idyllic meetings in summer. His reveries are interrupted when his neighbour Podtyagin has a heart attack.

9. Next day Alfyonov receives a telegram confirming his wife’s arrival at the week end. Ganin recalls the last of his summer meetings with Mary. They both return to St Petersburg in the autumn. They try but fail to consummate the relationship. In the war years that follow, they gradually lose touch with each other.

10. Lyudmila sends a message of complaint, but Ganin prepares to leave Berlin at the week end.

11. Ganin helps Podtyagin to apply for an exit visa – which the old man leaves on a bus.

12. Podtyagin despairs of his lost passport.

13. Ganin packs his suitcases and reads old letters from Mary – written to him whilst serving during the Civil War in Yalta.

14. There is an unsuccessful party at the pension to celebrate Ganin’s departure.

15. Ganin recalls his retreat from the war. Wounded in the head, he sails to Constantinople. The party in. The pension degenerates badly.

16. Mary’s husband Alfyonov passes out in a drunken stupor. In the early morning Ganin takes leave of the poet Podtyagin.

17. Ganin goes to the station to meet Mary and rescue her from her appalling husband. But he suddenly realises that she is now a completed memory that he must leave behind. He takes a train instead, heading for France and the Mediterranean coast.

Mary – principal characters

| Lev Glebovich Ganin | a young Russian exile in Berlin |

| Aleksey Ivanovich Alfyorov | the Russian husband of Mary |

| Lydia Nikolaevna Dorn | the landlady of the pension |

| Lyudmila Rubanski | Ganin’s lover in Berlin |

| Klara | a busty resident at the pension in love with Ganin |

| Anton Sergeyevich Podtyagin | an old popular Russian poet |

| Mary Alfyorov | Ganin’s youthful love, who never appears |

© Roy Johnson 2017

More on Vladimir Nabokov

More on literary studies

Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories

Phyllis and Rosamond for instance introduces many of the issues she explored in her later writings – the apparently empty lives of ordinary young women who went unrecognised by history; everyday life as a subject for fiction; the inequality of the sexes; and (almost as if Jane Austen were a contemporary) the ambiguous prospect of marriage as the only possible career structure for young females.

Phyllis and Rosamond for instance introduces many of the issues she explored in her later writings – the apparently empty lives of ordinary young women who went unrecognised by history; everyday life as a subject for fiction; the inequality of the sexes; and (almost as if Jane Austen were a contemporary) the ambiguous prospect of marriage as the only possible career structure for young females.

He worked as a secret agent, using multiple identities and the cover of a job as journalist and editor. His real job there was to assist the promotion of the German Revolution ‘planned’ for October 1923. This was a period when Marxist orthodoxy thought that revolutions could be planned and organised according to theoretical principles, without troubling to analyse or face any social facts. When the revolution failed to take place, he de-camped to Prague. However, even though conditions there were less severe, he felt unable to act effectively, and so, as a Trotsky supporting oppositionist and at the worst possible time, he loyally returned to Leningrad in 1926.

He worked as a secret agent, using multiple identities and the cover of a job as journalist and editor. His real job there was to assist the promotion of the German Revolution ‘planned’ for October 1923. This was a period when Marxist orthodoxy thought that revolutions could be planned and organised according to theoretical principles, without troubling to analyse or face any social facts. When the revolution failed to take place, he de-camped to Prague. However, even though conditions there were less severe, he felt unable to act effectively, and so, as a Trotsky supporting oppositionist and at the worst possible time, he loyally returned to Leningrad in 1926.

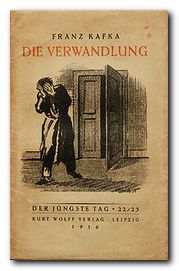

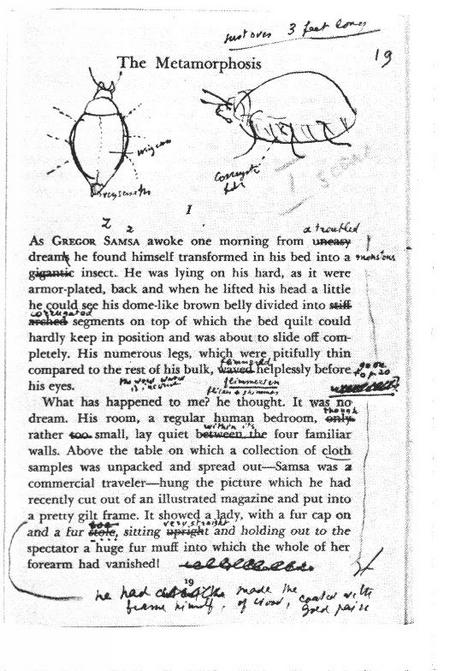

When Gregor’s supervisor arrives at the house and demands Gregor come out of his room, Gregor manages to roll out of bed and unlock his door. His appearance horrifies his family and supervisor; his supervisor flees while his family chases him back into his room.

When Gregor’s supervisor arrives at the house and demands Gregor come out of his room, Gregor manages to roll out of bed and unlock his door. His appearance horrifies his family and supervisor; his supervisor flees while his family chases him back into his room. Later, his parents take in lodgers and use Gregor’s room as a dumping area for unwanted objects. Gregor becomes dirty, covered in dust and old bits of rotten food. One day, Gregor hears Grete playing her violin to entertain the lodgers. Gregor is attracted to the music, and slowly walks into the dining room despite himself, entertaining a fantasy of getting his beloved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. The lodgers see him and give notice, refusing to pay the rent they owe, even threatening to sue the family for harboring him while they stayed there. Grete determines that the monstrous vermin is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. She suggests that they must get rid of it. Gregor retreats to his room and collapses, finally succumbing to his wound, and dying alone.

Later, his parents take in lodgers and use Gregor’s room as a dumping area for unwanted objects. Gregor becomes dirty, covered in dust and old bits of rotten food. One day, Gregor hears Grete playing her violin to entertain the lodgers. Gregor is attracted to the music, and slowly walks into the dining room despite himself, entertaining a fantasy of getting his beloved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. The lodgers see him and give notice, refusing to pay the rent they owe, even threatening to sue the family for harboring him while they stayed there. Grete determines that the monstrous vermin is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. She suggests that they must get rid of it. Gregor retreats to his room and collapses, finally succumbing to his wound, and dying alone. Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

The Trial

The Trial Amerika

Amerika

The Heart of a Dog

The Heart of a Dog Black Snow: A Theatrical Novel

Black Snow: A Theatrical Novel A Country Doctor’s Notebook

A Country Doctor’s Notebook The Fatal Eggs

The Fatal Eggs The Master and Margarita

The Master and Margarita life, works, political persecution

life, works, political persecution