Routledge Harwood Studies in Russian Literature

Vladimir Nabokov’s work has been widely regarded as an elaborate series of linguistic games in which a variety of clever and seductive narrators invite readers to collude in a system of aesthetic and moral beliefs which are held so firmly that to dissent from them would seem like heresy or not playing the game. Editor David Larmour explains the title of this collection of essays as an exploration of the ‘system of power relations in which the author, text, and reader are enmeshed’. In other words, Nabokov’s strategies are seen as open to challenge, with the clear implication that he has been getting away with it for far too long.

He is well known for his ‘strong opinions’, and some of his subject matter and authorial attitudes are very often seen as dubious – especially in Lolita, which gets special extended treatment here. Galya Diment starts the collection with her best efforts to defend Edmund Wilson from the damage inflicted on him by Nabokov in their now famous friendship-turned-dispute over the translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. Then Brian Walter makes a lengthy criticism of Bend Sinister to say not much more than that it is not one of his best novels.

He is well known for his ‘strong opinions’, and some of his subject matter and authorial attitudes are very often seen as dubious – especially in Lolita, which gets special extended treatment here. Galya Diment starts the collection with her best efforts to defend Edmund Wilson from the damage inflicted on him by Nabokov in their now famous friendship-turned-dispute over the translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. Then Brian Walter makes a lengthy criticism of Bend Sinister to say not much more than that it is not one of his best novels.

Galina Rylkova reveals a literary precedent for The Eye in a novel by Mikhail Kuzmin called Wings published in 1906. She has no problem in establishing the parallels between the two texts, but most of her lofty interpretive claims are undermined by her failure to see that Nabokov’s narrator Smurov is a self-deceiving liar and a totally unreliable narrator. He is a comic-pathetic character who is a vehicle for one of Nabokov’s most brilliant experiments in narrative – an experiment which was only matched in subtlety by his later Spring in Fialta.

David Larmour contributes an essay which looks at the relationship between sex and sport in Glory. But like many of the other contributors he accepts almost at face value what Nabokov has to say in his introductions – which were written at a later date. There is no acknowledgement of ‘Trust the tale, not the teller’, or ‘Death of the author’, whichever you prefer.

Paul Miller offers a chapter which demonstrates that Kinbote, narrator of Pale Fire is a homosexual – something which I would have thought any reader above the age of fifteen would realise without being told. There are some perceptive analyses of the American crewcut, but not much more than can be accessed by any reasonably attentive reader.

What struck me was how long it takes these writers to say so little. They come from what is now the bygone age of pre-Internet writing – one which persists in the modern world only thanks to the requirements of tenure in the US and the Research Assessment Exercise in the UK.

Tony Moore makes a valiant attempt to offer what he calls a feminist reading of Lolita, even enlisting the help of Camille Paglia, but his argument that Humbert Humbert changes his moral stance and his prose style at the end of the novel doesn’t seem very convincing, especially when it simply ignores the fact that Humbert is guilty of murder.

There’s also a full-on rad fem reading of Lolita from Elizabeth Patnoe which combines personal testimony and high moral outrage in a very unprofessional manner, ignoring any distinction between the worlds of fiction and reality. At the end of a long tortuous argument, one is left wondering why she bothers reading the novel.

She also has an annoying habit of describing almost every narrative twist as ‘doubling’ – a term she uses indiscriminately as a synonym for ‘ambiguous’, ‘dubious’, ‘disingenuous’, ‘devious’, ‘evasive’, and other related terms.

Fortunately the collection is rounded off by two sensible chapters by Donald Johnson and Suellen Stringer-Hye which place Nabokov in the context of popular culture and America in the 1960s. The collection is based on papers given at an academic conference. It’s obviously one for the literary specialist, but Nabokov enthusiasts will not want to miss it – even if it’s to sharpen their own critical analysis against the views being expressed.

© Roy Johnson 2004

David H.J.Larmour (ed), Discourse and Ideology in Nabokov’s Prose, London: Routledge, 2002, pp.176, ISBN 0415286581

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Yet when his wife bears him a male child (Paul junior) the son is immediately removed from his primary sources of emotional comfort – first of all from his mother because she dies, then from his beloved nurse, Polly Toodles, because Dombey fires her. Dombey then submits his son to the dubious care of his stupid sister Mrs Chick and her friend Miss Tox. Even worse, he subsequently sends Paul to the appalling establishment run by the fraudulent Mrs Pipchin in Brighton. She neglects the children placed in her care to an almost criminal extent.

Yet when his wife bears him a male child (Paul junior) the son is immediately removed from his primary sources of emotional comfort – first of all from his mother because she dies, then from his beloved nurse, Polly Toodles, because Dombey fires her. Dombey then submits his son to the dubious care of his stupid sister Mrs Chick and her friend Miss Tox. Even worse, he subsequently sends Paul to the appalling establishment run by the fraudulent Mrs Pipchin in Brighton. She neglects the children placed in her care to an almost criminal extent.

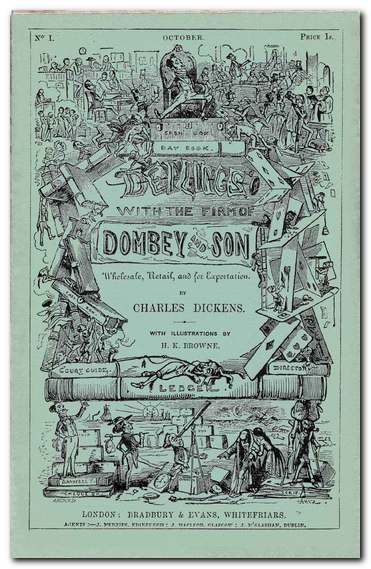

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens. Dora Carrington (1893-1932) was an artist and bohemian who loved and was loved by both men and women. She was born Dora de Houghton Carrington in Hereford, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. As a somewhat wilful youngster, she found her family background quite stifling, adoring her father and loathing her mother. She attended Bedford High School, which emphasized sports, music, and drawing. The teachers encouraged her drawing and her parents paid for her to attend extra art classes in the afternoons. In 1910 she won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London and studied there with Henry Tonks.

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) was an artist and bohemian who loved and was loved by both men and women. She was born Dora de Houghton Carrington in Hereford, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. As a somewhat wilful youngster, she found her family background quite stifling, adoring her father and loathing her mother. She attended Bedford High School, which emphasized sports, music, and drawing. The teachers encouraged her drawing and her parents paid for her to attend extra art classes in the afternoons. In 1910 she won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London and studied there with Henry Tonks.

Dorothy Eugenie Brett was born November 10, 1883. She was the eldest daughter of the second Viscount Esher, Reginald Baliol Brett, who was the Liberal MP for Penryn and Falmouth. Her mother was Eleanor van de Weyer, the daughter of the Belgian ambassador to the court of St. James and a close advisor to Queen Victoria. She was called ‘Doll’ by her family, and like many upper class children of the Victorian era she was raised separately from her parents, receiving little formal education. She went to dancing classes with members of the royal family at Windsor Castle under the supervision of Queen Victoria, but had little contact with other children her own age, apart from her two elder bothers and younger sister sylvia who scandalised the family by becoming the

Dorothy Eugenie Brett was born November 10, 1883. She was the eldest daughter of the second Viscount Esher, Reginald Baliol Brett, who was the Liberal MP for Penryn and Falmouth. Her mother was Eleanor van de Weyer, the daughter of the Belgian ambassador to the court of St. James and a close advisor to Queen Victoria. She was called ‘Doll’ by her family, and like many upper class children of the Victorian era she was raised separately from her parents, receiving little formal education. She went to dancing classes with members of the royal family at Windsor Castle under the supervision of Queen Victoria, but had little contact with other children her own age, apart from her two elder bothers and younger sister sylvia who scandalised the family by becoming the

English solicitor Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to visit Count Dracula, who has bought properties in London. He is hospitably received, but then is held prisoner in the castle, where he encounters three female vampires. Harker writes letters to his fiancée and employer asking for help, but Dracula intercepts them. Dracula then takes a boat journey to England. On the journey the entire crew disappear one by one. The ship is driven ashore at Whitby, Yorkshire during a violent storm.

English solicitor Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to visit Count Dracula, who has bought properties in London. He is hospitably received, but then is held prisoner in the castle, where he encounters three female vampires. Harker writes letters to his fiancée and employer asking for help, but Dracula intercepts them. Dracula then takes a boat journey to England. On the journey the entire crew disappear one by one. The ship is driven ashore at Whitby, Yorkshire during a violent storm. Van Helsing reads Lucy’s diaries and letters, then visits Mina and Jonathan in Exeter and reads the typed copies of their journals, which Mina has made. He then recruits John Seward to visit Lucy’s tomb, which turns out to be empty when they visit it at night. On returning in the daylight however, they find her there. He then recruits Arthur Holmwood and Quincy Morris, and the four men confront Lucy in her vampire mode outside the tomb. Next day they return in the daylight and Arthur drives a stake through her heart, following which Van Helsing cuts off her head.

Van Helsing reads Lucy’s diaries and letters, then visits Mina and Jonathan in Exeter and reads the typed copies of their journals, which Mina has made. He then recruits John Seward to visit Lucy’s tomb, which turns out to be empty when they visit it at night. On returning in the daylight however, they find her there. He then recruits Arthur Holmwood and Quincy Morris, and the four men confront Lucy in her vampire mode outside the tomb. Next day they return in the daylight and Arthur drives a stake through her heart, following which Van Helsing cuts off her head. This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century, ending with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. The book caused controversy when it first appeared, and was banned in Ireland almost immediately upon publication, the first of many of Joyce’s works to be censored or banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories.

This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century, ending with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. The book caused controversy when it first appeared, and was banned in Ireland almost immediately upon publication, the first of many of Joyce’s works to be censored or banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

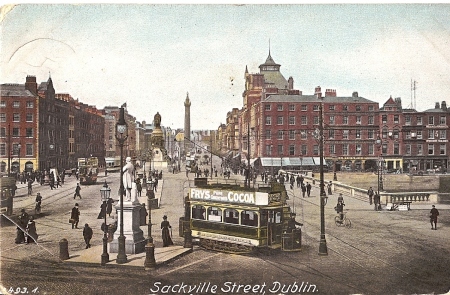

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return. Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day. The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

Duncan Grant (full name Duncan James Corrowr Grant) was born in Inverness, Scotland in 1885. He was brought up until the age of nine in India and Burma where his father was posted as an army officer. He returned to England in 1894 to attend school. While at St Paul’s school, London, he was brought up by his uncle and aunt Sir Richard and Lady Strachey (the parents of

Duncan Grant (full name Duncan James Corrowr Grant) was born in Inverness, Scotland in 1885. He was brought up until the age of nine in India and Burma where his father was posted as an army officer. He returned to England in 1894 to attend school. While at St Paul’s school, London, he was brought up by his uncle and aunt Sir Richard and Lady Strachey (the parents of