short biography and literary background

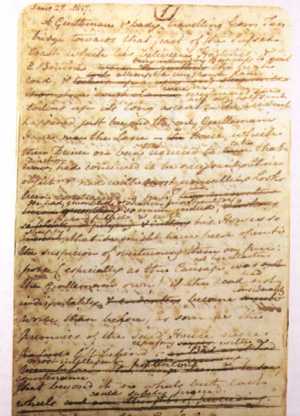

The new Very Interesting People series from Oxford University Press provides authoritative bite-sized biographies of Britain’s most fascinating historical figures. These are people whose influence and importance have stood the test of time. Each book in the series is based on the biographical entry from the world-famous Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Michael Slater sketches the main outline of Dickens’ life – the boyhood in Chatham and Rochester, his love of reading and amateur theatricals, and then the shocking, seminal event in his young life when his father was put into the Marshalsea debtor’s prison and Dickens himself was set to work in a blacking factory, sticking labels on bottles. This was an event which was to shape much of his later fiction, as well as his own psychology and his attitudes to social reform.

After this difficult start to life, and despite being very largely self-educated, he fought his way into literature via journalism and court reporting. By the time he was in his mid twenties he had catapulted himself to fame with Pickwick Papers. Thereafter, he became a cultural and publishing phenomenon, producing masterpieces at a rate that puts most of today’s writers to shame.

After this difficult start to life, and despite being very largely self-educated, he fought his way into literature via journalism and court reporting. By the time he was in his mid twenties he had catapulted himself to fame with Pickwick Papers. Thereafter, he became a cultural and publishing phenomenon, producing masterpieces at a rate that puts most of today’s writers to shame.

On the strength of this success he married and settled down to a life of stupendous creativity and some amazing enterprise. He was active in controlling his own commercial potential as a writer, and he campaigned vigorously on the cause for authors’ copyright.

His fame also led him to develop a parallel career as a public speaker, and he gave regular dramatised readings from his own works, travelling to America on lecture tours and taking holidays in France and Italy.

Slater’s account manages to balance aspects of Dickens’ personal life with the development of his literary work. For instance, he doesn’t shirk the fact that Dickens like many other rich middle-class Victorian men became interested in the plight of ‘fallen women’, but at the same time he was able to produce his great masterpieces in books such as Dombey and Son, Bleak House, and Little Dorrit.

Yet whilst his fame spread and both his family and his bank-balance grew, his marriage slid into the doldrums, and he made matters worse by falling in love with Ellen Ternan, an actress the same age as his own young daughter.

The later years of his life appear to have been tinged with darkness. His relationships with his (ten) children was not good; he seems to have been implacably hostile to his wronged wife; and his health was not robust. Nevertheless, he worked on – and eventually it was his work rate and his dramatic readings which cut short his life at fifty-eight.

For a publication of this size, there’s a lot of inline source referencing that takes up space which could have been much better used by offering a bibliography and suggestions for further reading. But it’s a book which you can be quite confident is based on a scholarly knowledge of its subject. Most importantly, it makes you want to read the great works – or even better read them again.

© Roy Johnson 2007

Michael Slater, Charles Dickens, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, pp.111, ISBN: 0199213528

More on Charles Dickens

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Sense and Sensibility (1811) casts two young and marriageable sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood as representatives of ‘sense’ and ‘sensibility’ respectively. Elinor bears her social disappointments with dignity and restraint – and thereby gets her man. Marianne on the other hand is excitable and impetuous, following her lover to London – where she quickly becomes disillusioned with him. Recovering and gaining more ‘sense’, she then finally sees the good qualities in her old friend Colonel Brandon, who has been waiting in the wings and is now conveniently on hand to propose marriage.

Sense and Sensibility (1811) casts two young and marriageable sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood as representatives of ‘sense’ and ‘sensibility’ respectively. Elinor bears her social disappointments with dignity and restraint – and thereby gets her man. Marianne on the other hand is excitable and impetuous, following her lover to London – where she quickly becomes disillusioned with him. Recovering and gaining more ‘sense’, she then finally sees the good qualities in her old friend Colonel Brandon, who has been waiting in the wings and is now conveniently on hand to propose marriage. Northanger Abbey (1818) opens in the drawing rooms of Bath. The heroine is imaginative Catherine Morland who falls in love with Henry Tilney, a young clergyman. When he invites her to meet his family at the Abbey however, she sees nothing but Gothic melodrama at every turn – since they were very fashionable at the time. Her visions of medieval horror prove groundless of course. This is Jane Austen’s satirical critique of Romantic cliché and excess. But Catherine eventually learns to see the world in a realistic light – and gets her man in the end. This volume also contains the early short novels Lady Susan and The Watsons, as well as the unfinished Sanditon.

Northanger Abbey (1818) opens in the drawing rooms of Bath. The heroine is imaginative Catherine Morland who falls in love with Henry Tilney, a young clergyman. When he invites her to meet his family at the Abbey however, she sees nothing but Gothic melodrama at every turn – since they were very fashionable at the time. Her visions of medieval horror prove groundless of course. This is Jane Austen’s satirical critique of Romantic cliché and excess. But Catherine eventually learns to see the world in a realistic light – and gets her man in the end. This volume also contains the early short novels Lady Susan and The Watsons, as well as the unfinished Sanditon. Mansfield Park (1814) is more serious after the comedy of the earlier novels. Heroine Fanny Price is adopted into the family of her rich relatives. She is long-suffering and passive to a point which makes her almost unappealing – but her refusal to tolerate any drop in moral standards eventually teaches lessons to all concerned. (All that is except standout character Mrs Norris who is a sponging and interfering Aunt you will never forget.) The hero Edmund is dazzled by sexually attractive Mary Crawford – but in the nick of time sees the error of his ways and marries Fanny instead. Slow moving, but full of moral subtleties.

Mansfield Park (1814) is more serious after the comedy of the earlier novels. Heroine Fanny Price is adopted into the family of her rich relatives. She is long-suffering and passive to a point which makes her almost unappealing – but her refusal to tolerate any drop in moral standards eventually teaches lessons to all concerned. (All that is except standout character Mrs Norris who is a sponging and interfering Aunt you will never forget.) The hero Edmund is dazzled by sexually attractive Mary Crawford – but in the nick of time sees the error of his ways and marries Fanny instead. Slow moving, but full of moral subtleties. Emma (1816) Charming and wilful Emma Woodhouse amuses herself by dabbling in other people’s affairs, planning their lives the way she sees fit. Most of her match-making plots go badly awry, and moral confusion reigns until she abandons her self-delusion and wakes up to the fact that stern but honourable Mr Knightly is the right man for her after all. As usual, money and social class underpin everything. Some wonderful comic scenes, and a rakish character Frank Churchill who finally reveals his flaws by making the journey to London just to get his hair cut.

Emma (1816) Charming and wilful Emma Woodhouse amuses herself by dabbling in other people’s affairs, planning their lives the way she sees fit. Most of her match-making plots go badly awry, and moral confusion reigns until she abandons her self-delusion and wakes up to the fact that stern but honourable Mr Knightly is the right man for her after all. As usual, money and social class underpin everything. Some wonderful comic scenes, and a rakish character Frank Churchill who finally reveals his flaws by making the journey to London just to get his hair cut. Persuasion (1818) is the most mature of her novels, if one of the least exciting. Heroine Anne Elliott has been engaged to Captain Wentworth, but has broken off the engagement in deference to family and friends. Meeting him again eight years later, she goes against conventional wisdom and accepts his second proposal of marriage. Anne is a sensitive and thoughtful character, quite unlike some of the earlier heroines. Jane Austen wrote of her “She is almost too good for me”. There is a shift of location to Lyme Regis for this novel, which reveals for the first time a heroine acting from a deep sense of personal conviction, against the grain of conventional wisdom.

Persuasion (1818) is the most mature of her novels, if one of the least exciting. Heroine Anne Elliott has been engaged to Captain Wentworth, but has broken off the engagement in deference to family and friends. Meeting him again eight years later, she goes against conventional wisdom and accepts his second proposal of marriage. Anne is a sensitive and thoughtful character, quite unlike some of the earlier heroines. Jane Austen wrote of her “She is almost too good for me”. There is a shift of location to Lyme Regis for this novel, which reveals for the first time a heroine acting from a deep sense of personal conviction, against the grain of conventional wisdom.

[2]

[2]