collected essays, articles, and reviews

Marxists have always had a problem with theorising Art. Radical proposals for changing the State and replacing the power of one class with that of another does not sit easily with a taste for Beethoven, Michaelangelo, and Marcel Proust. And political sympathy for an oppressed class (the proletariat) has often resulted in wishing its artistic achievements into being. When a revolution (of sorts) did take place in St Petersburg in 1917, expectations were high that a different art would be formed in the new type of society. And at first it did start to happen. The graphic art of Rodchenko and El Lissitzsky, the architecture of Tatlin, and the poetry of Mayakovsky produced a native form of modernism whose influence is still alive today, almost one hundred years later. Literature and Revolution is Victor Serge’s on-the-spot essays engaging with the new literary endeavours of the period.

But none of these artists were working class, and before long Party apparatchiks were calling for the suppression of their work and demanding art that followed the Party line. Since the party had a monopoly of the means of production and even the supply of paper, they got what they called for. The result was worthless propaganda of the ‘boy meets tractor’ variety.

But none of these artists were working class, and before long Party apparatchiks were calling for the suppression of their work and demanding art that followed the Party line. Since the party had a monopoly of the means of production and even the supply of paper, they got what they called for. The result was worthless propaganda of the ‘boy meets tractor’ variety.

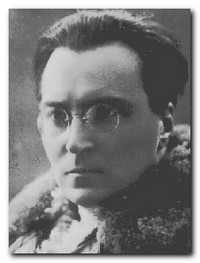

Victor Serge was able to avoid these ideological traps more than his contemporaries (and his predecessors) for two good reasons. The first was that throughout his life he retained a critical integrity that kept him free from any Party line prejudice. The second was that unlike many of the so-called theorists of his time, he was a practising artist. Even though he worked in the most appalling circumstances and spent the last twenty years of his life in exile, he produced two excellent trilogies of novels, as well as his amazing memoirs and other works.

The first part of this collection of his writings is on the subject of literature and politics, under the title of ‘The Theory of Proletarian Literature’. Serge is defending the political gains of the revolution and pointing out quite rightly that the proletariat is too busy defending itself and producing enough to sustain life to be creating great works of art.

The development of any intellectual culture takes for granted stable production, a high level of technique, well-being, leisure and time.

The so-called proletarian writing produced under Party diktat turned out to be entirely schematic, with heroes ‘bearing no resemblance to any human being one had actually ever met.’ But his argument is that this was to be expected.

The second part of the book is a collection of critical essays on literary topics written in the heat of events during the early 1920s. It’s interesting to note that they were all published in France – a fact which established Serge’s reputation outside Russia and later helped to save his life when he was granted permission to leave Russia at a time when his contemporaries were simply being shot.

These essays provide what’s called ‘A Chronicle of Intellectual Life in the Soviet Union’. Apart from beating the drum for Russian achievements at a time of austerity and shortages, the only artists to emerge from this honourably are the poets – Blok, Biely, Yesenin, and especially Mayakovsky, whom Serge puts into a category of his own, presumably because he was the most committed Bolshevik and therefore (in 1922) above criticism. The only other writer to emerge with laurels is Leon Trotsky, whose own Literature and Revolution closely resembles Serge’s own work.

There’s a section on individual writers – tributes to the poet Blok, novelist Boris Pilnyak who was an influence on Serge’s own literary style (shot during the purges) Gorky and Mayakovsky. Because so many of these articles were written during the early 1920s they have an optimistic tone and they speak of literary potential which is yet to be fully realised. Knowing as we do what happened shortly afterwards, they have a sort of unreality about them. It is therefore fortunate that the collection ends with appreciative notes on some of the same writers as they began to ‘disappear’ in the purges of the mid 1930s and onwards. This is why Serge was happy to accept Trotsky’s description of ‘the revolution betrayed’.

It is a dark but honest note on which to end the collection – his outrage at the murder of Osip Mandelstam and countless others in the purges, but it confirms that his line of argument on politics and literature was consistent, and it has been proved to be true.

Serge never fell into any of the crude over-simplifications of propagandist writing in his own fictional creations. His artistic practice was based firmly on the literary traditions which he and his fellow theorists would call ‘bourgeois’, and even though his material existence was light years away from the comforts of the western literary world of 1920-1945, he was in his own way a contributor to ‘modernism’.

He removed the central ‘I’ from the controlling individual consciousness of his narratives, and put in its place a more general ‘We’. That was his conscious political choice. We read his novels and come away with a sense of collectives or representatives of general social tendencies, rather than Big Individuals.

And his other literary techniques fit comfortably alongside other literary modernists – from Conrad to Woolf and Beckett. He uses extended metaphors, repeated motifs, sparkling imagery, blurs the distinctions between prose and poetry, flits from one point of view to another with no clunky connecting passages, and has what might be called a ‘mosaic’ rather than a linear approach to narrative.

Serge survived in terrible conditions in Mexican exile until 1946, and thank goodness he was able to produce his finest novels in those last years. The Case of Comrade Tulayev, Unforgiving Years, and The Long Dusk stand as testaments to a passionate belief in truth, a militant critic, and a great artist.

© Roy Johnson 2010

Victor Serge, Collected Writings on Literature and Revolution, London: Francis Boutle Publishers, 2004, pp.367, ISBN: 1903427169

More on Victor Serge

Twentieth century literature

More on biography

There were memorable and enduring works written during the conflict — Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire (1916) and the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Edward Thomas. However, the majority of works which seem to encapsulate both the horrors of the war and the almost universal sense of disillusionment which followed were produced almost a decade later — Robert Graves Goodbye to All That (1929), Ernest Hemingway A Farewell to Arms (1929), Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero (1929), Siegfried Sassoon Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), R.C. Sheriff Journey’s End (1929), Erich Maria Remarque All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

There were memorable and enduring works written during the conflict — Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire (1916) and the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Edward Thomas. However, the majority of works which seem to encapsulate both the horrors of the war and the almost universal sense of disillusionment which followed were produced almost a decade later — Robert Graves Goodbye to All That (1929), Ernest Hemingway A Farewell to Arms (1929), Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero (1929), Siegfried Sassoon Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), R.C. Sheriff Journey’s End (1929), Erich Maria Remarque All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

He worked as a secret agent, using multiple identities and the cover of a job as journalist and editor. His real job there was to assist the promotion of the German Revolution ‘planned’ for October 1923. This was a period when Marxist orthodoxy thought that revolutions could be planned and organised according to theoretical principles, without troubling to analyse or face any social facts. When the revolution failed to take place, he de-camped to Prague. However, even though conditions there were less severe, he felt unable to act effectively, and so, as a Trotsky supporting oppositionist and at the worst possible time, he loyally returned to Leningrad in 1926.

He worked as a secret agent, using multiple identities and the cover of a job as journalist and editor. His real job there was to assist the promotion of the German Revolution ‘planned’ for October 1923. This was a period when Marxist orthodoxy thought that revolutions could be planned and organised according to theoretical principles, without troubling to analyse or face any social facts. When the revolution failed to take place, he de-camped to Prague. However, even though conditions there were less severe, he felt unable to act effectively, and so, as a Trotsky supporting oppositionist and at the worst possible time, he loyally returned to Leningrad in 1926.