Bloomsbury and the decorative arts

The Bloomsbury Group was largely composed of writers and intellectuals, but there were lots of artists and designers within their ranks too. This well illustrated guide focuses on the highpoint of their endeavours – the Omega Workshops which flourished in the period 1913—1919. This venture was the brainchild of Roger Fry, who recruited Vanessa Bell (his lover at the time) and Duncan Grant as co-directors for an opening in Fitzroy Square in 1913, deep in the heart of Bloomsbury.

That was not an auspicious date for the debut of an enterprise which sought to bring Post-Impressionist design to the general public. But in fact it survived throughout the whole of the first world war, even though it was never commercially successful. Fry organised painters, designers, and ceramicists to supply goods which were colourfully and playfully made to bring Modern Art into the home – of those who could afford it. Although the works were produced by people we now see as influential members of the modernist movement in the arts, individual productions were made anonymously, signed only with the letter omega.

That was not an auspicious date for the debut of an enterprise which sought to bring Post-Impressionist design to the general public. But in fact it survived throughout the whole of the first world war, even though it was never commercially successful. Fry organised painters, designers, and ceramicists to supply goods which were colourfully and playfully made to bring Modern Art into the home – of those who could afford it. Although the works were produced by people we now see as influential members of the modernist movement in the arts, individual productions were made anonymously, signed only with the letter omega.

A number of famous names were associated with the workshop: at one time or another Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Paul Nash, David Bomberg, Dora Carrington, William Roberts, and Mark Gertler all had connections with the Omega.

At the launch of the project, artist and writer Wyndham Lewis was also a member; but he quickly split away from the group in a dispute over Omega’s contribution to the Ideal Homes Exhibition. Lewis circulated a letter to all shareholders, making accusations against the company and Roger Fry in particular, and pouring scorn on the products of Omega and its ideology. This subsequently led to his establishing the rival Vorticist movement and the publication in 1916 of its two-issue house magazine, BLAST.

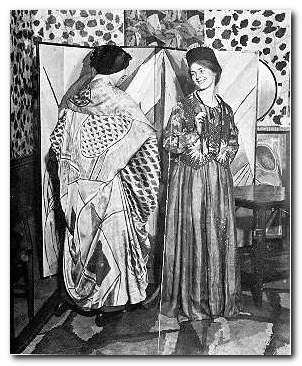

The Omega workshops produced everything, from furniture and paintings to rugs, wallpaper, and children’s toys. All of these are wonderfully illustrated in this collection of photographs which are rarely seen anywhere else.

The text recounts the story of the enterprise and its shaky beginnings. A somewhat amateurish co-operative; the introduction of modernist clothes via Nina Hamnet (the Queen of Bohemia); and the tortured love triangle which existed between its directors.

Isabelle Anscombe devotes an entire chapter to Vanessa Bell, studiously avoiding for as long as she can the fact that she was Roger Fry’s lover; but she is forced to eventually concede that Fry was replaced by Duncan Grant. Her husband Clive Bell, who was friendly with all three of them, is kept out of the picture altogether.

The latter part of the book (the ‘After’ of her title) follows the fortunes of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant as they continued their work in decorative arts, at the same time as tracing developments in contemporary design taste in Britain. Both of them continued to put all their decorative efforts into their house at Charleston – which is now a museum to Bloomsbury and its visual culture.

But ultimately, it is the wonderful illustrations which are the centre of interest here: interiors, ceramics, fabrics, book jackets, and portrait photographs of the principal artists. This book is well worth tracking down for anybody with an interest in the decorative arts and the visually creative side of Bloomsbury.

© Roy Johnson 2000

Isobelle Anscombe, Omega and After: Bloomsbury and the Decorative Arts, London: Thames and Hudson, 1984, pp.176, ISBN 0500273626

More on design

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature