Hogarth Press first edition book jacket designs

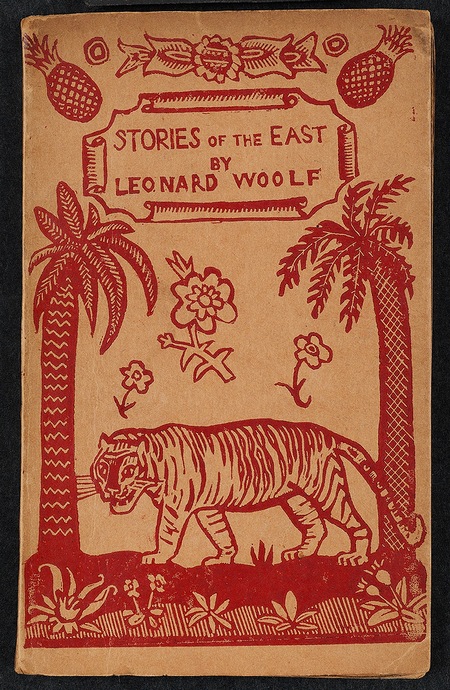

Leonard Woolf, Stories of the East (1919)

This publication contained three short stories – ‘Pearls and Swine’, ‘A Tale Told by Midnight’, and ‘The Two Brahmans’, with a cover illustration by Dora Carrington.

These three pieces are of vital importance in understanding Leonard Woolf’s mistrust of and dislike for colonialism. The stories provide disturbing commentaries about the disintegration of the colonial process and the uncomfortable moral ground occupied by the servants of the British Government in Ceylon prior to the Great War.

“Stories of the East was published in April 1921 in 300 copies and very nearly sold out. At the end of the first year, the Hogarth Press had sold over 230 copies, to realise a profit of £6 11s. 5d. When Leonard Woolf closed the account in January 1924, Stories of the East had sold 267 copies. Of the six books published by Hogarth in 1925, Leonard’s stories outsold all but Gorky’s second book, The Notebooks of Tchekhov and Virginia’s Monday or Tuesday, and in the scale of press operations it was a successful venture.”

J.H. Willis Jr, Leonard and Virginia Woolf as Publishers: The Hogarth Press 1917-1941

This book had a yapp binding, as does Prelude, and Eliot’s Poems. Dating from the nineteenth century, the yapp binding is limp, with “overlapping flaps or edges on three sides” and was originally used for binding Bibles meant to be carried in the pocket.

Elizabeth Willson Gordon, Woolf’s-head Publishing: The Highlights and New Lights of the Hogarth Press

Hogarth Press studies

Woolf’s-head Publishing is a wonderful collection of cover designs, book jackets, and illustrations – but also a beautiful example of book production in its own right. It was produced as an exhibition catalogue and has quite rightly gone on to enjoy an independent life of its own. This book is a genuine collector’s item, and only months after its first publication it started to win awards for its design and production values. Anyone with the slightest interest in book production, graphic design, typography, or Bloomsbury will want to own a copy the minute they clap eyes on it.

Woolf’s-head Publishing is a wonderful collection of cover designs, book jackets, and illustrations – but also a beautiful example of book production in its own right. It was produced as an exhibition catalogue and has quite rightly gone on to enjoy an independent life of its own. This book is a genuine collector’s item, and only months after its first publication it started to win awards for its design and production values. Anyone with the slightest interest in book production, graphic design, typography, or Bloomsbury will want to own a copy the minute they clap eyes on it.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Leonard and Virginia Woolf as Publishers: Hogarth Press, 1917-41 John Willis brings the remarkable story of Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s success as publishers to life. He generates interesting thumbnail sketches of all the Hogarth Press authors, which brings both them and the books they wrote into sharp focus. He also follows the development of many of its best-selling titles, and there’s a full account of the social and cultural development of the press. This is a scholarly work with extensive footnotes, bibliographies, and suggestions for further reading – but most of all it is a very readable study in cultural history.

Leonard and Virginia Woolf as Publishers: Hogarth Press, 1917-41 John Willis brings the remarkable story of Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s success as publishers to life. He generates interesting thumbnail sketches of all the Hogarth Press authors, which brings both them and the books they wrote into sharp focus. He also follows the development of many of its best-selling titles, and there’s a full account of the social and cultural development of the press. This is a scholarly work with extensive footnotes, bibliographies, and suggestions for further reading – but most of all it is a very readable study in cultural history.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2005

He became an Anglican clergyman, but in 1865 renounced his religious beliefs and left the church. In 1869 he married Harriet Thackeray, the daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray. They had a daughter Laura (1870-1945) who developed a form of incurable brain disease and was institutionalised for the majority of her life. When his wife died rather suddenly in 1875 he married Julia Prinsep Jackson, the widow of Herbert Duckworth. She brought with her two sons, George and Gerald, the latter of whom went on to found the Duckworth publishing company.

He became an Anglican clergyman, but in 1865 renounced his religious beliefs and left the church. In 1869 he married Harriet Thackeray, the daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray. They had a daughter Laura (1870-1945) who developed a form of incurable brain disease and was institutionalised for the majority of her life. When his wife died rather suddenly in 1875 he married Julia Prinsep Jackson, the widow of Herbert Duckworth. She brought with her two sons, George and Gerald, the latter of whom went on to found the Duckworth publishing company.

But none of these artists were working class, and before long Party apparatchiks were calling for the suppression of their work and demanding art that followed the Party line. Since the party had a monopoly of the means of production and even the supply of paper, they got what they called for. The result was worthless propaganda of the ‘boy meets tractor’ variety.

But none of these artists were working class, and before long Party apparatchiks were calling for the suppression of their work and demanding art that followed the Party line. Since the party had a monopoly of the means of production and even the supply of paper, they got what they called for. The result was worthless propaganda of the ‘boy meets tractor’ variety. There were memorable and enduring works written during the conflict — Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire (1916) and the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Edward Thomas. However, the majority of works which seem to encapsulate both the horrors of the war and the almost universal sense of disillusionment which followed were produced almost a decade later — Robert Graves Goodbye to All That (1929), Ernest Hemingway A Farewell to Arms (1929), Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero (1929), Siegfried Sassoon Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), R.C. Sheriff Journey’s End (1929), Erich Maria Remarque All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

There were memorable and enduring works written during the conflict — Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire (1916) and the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Edward Thomas. However, the majority of works which seem to encapsulate both the horrors of the war and the almost universal sense of disillusionment which followed were produced almost a decade later — Robert Graves Goodbye to All That (1929), Ernest Hemingway A Farewell to Arms (1929), Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero (1929), Siegfried Sassoon Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), R.C. Sheriff Journey’s End (1929), Erich Maria Remarque All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

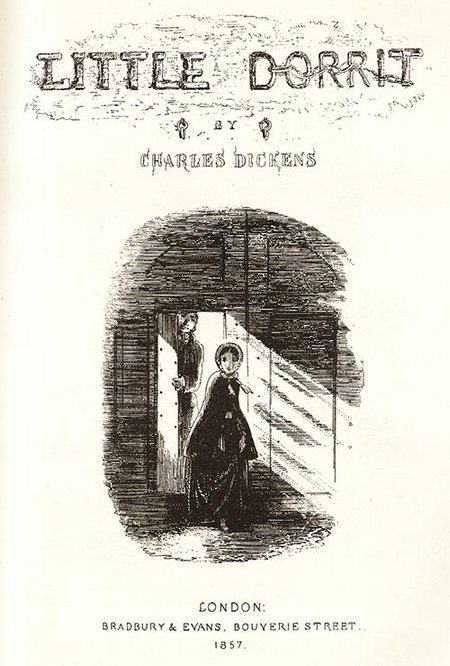

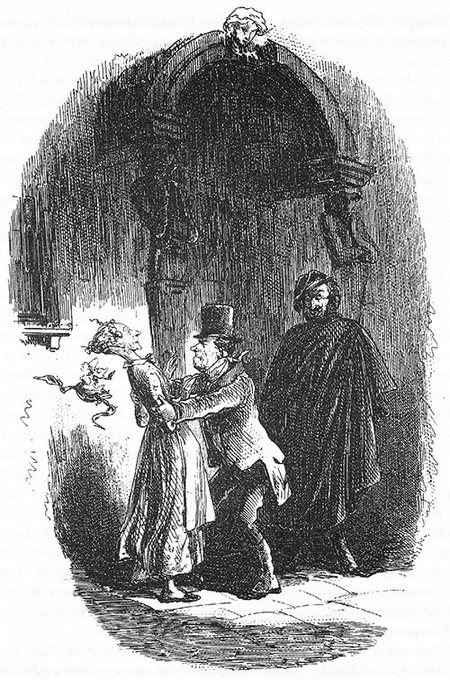

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.