an alternative history of American popular music

How the Beatles Destroyed Rock N Roll is a serious and well-informed piece of cultural criticism. I am no committed student of rock and roll, though my life to date, from about ten years onwards spans that of rock and roll and much else in the world of pop music. I’ve always enjoyed it without really knowing why, and for me popular music was never the inevitable concomitant of dancing. As a history of American music this is a solid, well researched and interesting book.

Elijah Wald has an encyclopaedic knowledge of his subject plus a shrewd understanding of the business side of the pop music industry; and this is one field of music-popular entertainment – where money is more central than any other. He fills out his narrative from Ragtime and early Jazz to the Twist and Rock- folk with a dazzling array of talent, social history and, unsurprisingly race relations.

Elijah Wald has an encyclopaedic knowledge of his subject plus a shrewd understanding of the business side of the pop music industry; and this is one field of music-popular entertainment – where money is more central than any other. He fills out his narrative from Ragtime and early Jazz to the Twist and Rock- folk with a dazzling array of talent, social history and, unsurprisingly race relations.

But to get to the Beatles thread, Wald sees the Liverpool foursome as a typical late fifties group, travelling around local dance-halls playing covers of other records to young kids who wanted to dance. I was one of them as it happens – in 1963 they played at the Shrewsbury Music Hall and I was there as someone trying to dance (I never learnt).

But the Beatles were not so typical as Wald himself supposes. Far from it. They were unusual in that they did not survive on a diet of material supplied by song writers, beavering away for record companies. They dared to write their own songs and this meant they could direct their own careers more closely than others less talented. They could also introduce trends which others followed.

So, after an early focus on rock and roll – covers of Chuck Berry and some rockers of their own like She was Just Seventeen – they produced a sentimental but haunting song, Yesterday, to link up with that earlier tradition of ballads. This song was of course a worldwide hit and soon there were nearly 200 covers of it by different artists. The ability of the Beatles to influence others was clearly immense as their popularity went global in the late sixties.

Wald argues they distracted white kids from getting into black soul, causing them instead to regress to sentimental ballads, paving the way for Simon and Garfunkel, Crosby Stills Nash and Young, Elton John and the like. Then they became more pretentious and got into meditation, clothing their music with arty mystification and letting loose the likes of The Velvet Underground, Pink Floyd, and yes, Led Zeppelin. Then a whole galaxy of sub sects were spawned which are still developing and mutating.

I’m sure there is something in this. Even McCartney says of Yesterday “we didn’t release Yesterday as a single in England at all because we were a little embarrassed by it; we were a rock and roll band”. Rock music is very imitative – witness how many US performers produced ‘Beatlified’ songs to jump on the new British bandwagon. Wald also points out that after 1966 the Beatles did not perform live but were closeted in their studios making more advanced, experimental pop music – as George Harrison joked: “our avant garde a clue music”.

With Sgt Pepper, moreover, they refused to issue any singles. Wald describes these albums as ‘musical novels’ or ‘art’; all this of a different order to the two to three minute thrashes of fifties rock and roll which had drawn them into the business. Soon rock and roll’ became a word to describe a historical period in popular music; a more generic ‘rock’ was what followed the post Beatles period.

Wald makes another interesting point regarding the white and black wings of the business. While both black and white artist were aiming at the same audience up to the mid to late sixties, he claims the Beatles marked a bifurcation into the more sophisticated white-appealing ‘rock folk’ and the more rhythmically complex black-appealing ‘soul’.

I hope I’ve summarised his argument sufficiently. Does it stack up? I think it does – but I have two doubts about it. First I don’t think you can attribute everything since the late sixties to the Beatles. I would reckon Bob Dylan had an equal influence on charting the new directions, along with the likes of Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen and Eric Clapton.

Second I’m not sure there was ever such a separation between black and white audiences. I recall a universal acclaim for both Beatles music and Tamla for example. But I recommend this book for anyone wishing to gain a grasp of why rock and roll lost its rebellious snarl and its sneer, its thundering, testosterone celebration of youthful sexuality and became more serene, thoughtfully wistful and poetic.

© Bill Jones 2009

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Elijah Wald, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock n Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp.336, ISBN: 0195341546

More on music

More on media

More on lifestyle

guidance notes for beginners

guidance notes for beginners

Musicians with good taste always pay respect to the tune they are playing. If saxophonists such as Dexter Gordon or

Musicians with good taste always pay respect to the tune they are playing. If saxophonists such as Dexter Gordon or

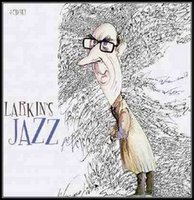

The second disc collects some of the music he experienced at University, along with fellow student Kingsley Amis who became a lifelong friend. Outstanding names here include Bix Beiderbecke, Eddie Condon, Muggsy Spanier, and Gene Krupa. You might be tempted to conclude from this that his taste was mainly for white musicians, but to his credit Larkin was an early enthusiast for blues singers such as Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday.

The second disc collects some of the music he experienced at University, along with fellow student Kingsley Amis who became a lifelong friend. Outstanding names here include Bix Beiderbecke, Eddie Condon, Muggsy Spanier, and Gene Krupa. You might be tempted to conclude from this that his taste was mainly for white musicians, but to his credit Larkin was an early enthusiast for blues singers such as Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday.