tutorial, commentary, study resources, characters, and plot

Bleak House was first published in nineteen monthly instalments between March 1852 and September 1853, the final instalment being a double issue, as was common practice. On completion it was then produced as a single volume novel by Bradbury and Evans in the UK, and a two-volume version was issued in the USA by Harper and Brothers. The novel was a great favourite with the reading public immediately on its first appearance.

Bleak House – critical commentary

The title

Dickens took great care in choosing the titles for his novels – as well as the names for his characters. He drew up lists of possibilities, and for quite some time during the composition of Bleak House his choice for the title was the much more suitable In Chancery.

This term ‘In Chancery’ sums up the central issue of the legal process that is at the heart of events in the narrative. The Court of Chancery pervades the entire story, and characters caught up in the legal proceedings of Jarndyce and Jarndyce recognise each other as if they were inhabitants of a parallel universe. They even refer to each other as ‘claimants’, ‘parties’, ‘suitors’, ‘creditors’, and ‘wards in Chancery’. [In the early twentieth century the novelist John Galsworthy used the term for In Chancery (1920), the second novel in his Forsyte Saga trilogy.]

The house that gives the novel its title is anything but ‘bleak’. It is in fact an elegant mansion with many of the features of a country house. The building is ‘pretty’ with trellises for ‘roses and honey-suckle’. Its interior is pleasant; there are fires in all the rooms; there’s a library; and the salons look out onto gardens which are ‘delightful’. It is also a place of comfort and refuge for Esther, Ada, and Richard, thanks to the hospitality and generosity of John Jarndyce.

This architectural pleasantness is reinforced when Jarndyce chooses and furnishes a country house for Allan Woodcourt’s medical practice in Yorkshire. He not only reproduces the style and decorative features of his home in St Albans, but he even calls it ‘Bleak House’ .

So the eponymous house might well be called ‘Bleak House’, but it isn’t bleak at all and it does not summarise or symbolise the novel as a whole. The elements of ‘bleakness’ in the novel arise more from the Court of Chancery itself, the poverty of the surrounding districts of London; and the moral bankruptcy of the Dedlock household at Chesney Wold.

All those editions of the novel which are illustrated by jacket covers depicting grim mansions in gothic settings are quite inaccurate and misleading – though it may well be that they summarise the negative and all-pervasive influence of the legal ‘proceedings’ that brought the original family dispute of Jarndyce and Jarndyce to trial in the first place.

The narrative

The events of the novel are recounted in two parts which run parallel to each other — the chapters in which Dickens writes as a third person omniscient narrator, and those designated as ‘Esther’s Narrative’ in which Ester Summerson records her part in the events of the story – in first person narrative mode.

This is a simplified description of the narrative. The actual presentation of the story is much more complex. The chapters narrated by Dickens are a mixture of omniscient third person narrative mode, and Dickens himself as an undeclared first-person commentator on events. He offers long and satirical tirades against the law and the upper class in quite an oblique manner – using sentences with no subject, no verb, and an implied contract of outraged agreement between author and reader, as in the death scene of Jo, the child crossing sweeper:

Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, Right Reverends and Wrong Reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with Heavenly compassion in your hearts, And dying thus around us, every day.

Now a purist might wish to argue that we cannot assume that the third person narrator is Dickens himself, and that we must therefore designate the narrator as ‘anonymous’. Some would even claim that he is not even omniscient, because he occasionally tells that there are things he does not know. This does not seem a persuasive argument to me, on three grounds.

First, there is no evidence that Dickens was constructing an independent narrator – that is, someone with a personality or a particular point of view which we could regard almost as a participating character in the novel as a whole, as he does in the case of Esther. Second, as already mentioned, the narrative in these chapters is actually cast in a mixture of first and third person modes.

But third, and it seems to me most persuasive reason of all, these chapters are presented to us in exactly the same manner and with the same ‘voice’ as most of Dickens’s other novels. Indeed, that is what makes them so distinctively ‘Dickensian’. He creates narratives that are a mixture of detached observation, scenes alternatively comic, grotesque, and full of pathos, and plots full of tension and mystery. These elements are stitched together with the control of something like a circus ringmaster, commenting on his own creation, and offering satirical and sometimes bitterly ironic analyses of society and its ills.

This is exactly what gives his novels such a powerful appeal to readers of all kinds. It is almost impossible to read Bleak House or most of Dickens’s other works without feeling the enormous presence of his personality as an author present in the works themselves.

Esther’s narrative

Esther’s narrative is cast in a fairly straightforward first person mode which also includes a sometimes naive and unselfconscious point of view. For instance it will be clear to most readers that she is romantically smitten by Allan Woodcourt – which is obvious from the fact that she avoids talking about him, but is flustered in a way she cannot understand whenever she has met him. In this case the reader knows more than she knows herself.

But the inclusion of her narrative chapters raises two problems in terms of the ‘logic’ of story telling. The first of these is that Dickens provides no explanation for the relationship between these two parts of the story. There is certainly no mention of Esther or her account of events in the chapters relayed by the third person narrator. Conversely (and fortunately) Esther makes no reference to the ‘outer narrative’ in which her own account is embedded.

There is simply no reason or justification given in the chapters related by Dickens of how Esther’s narrative comes into being (via the discovery of a diary or letters for instance). In other words, no satisfactory account is provided for the co-existence or the relationship between these two separate parts of the novel. Esther herself gives no convincing reason for the existence of her narrative: she merely claims to be writing for an ‘unknown friend’. This seems distinctly unpersuasive.

First, it is more than slightly improbable that someone like Esther would compile such a comprehensive ‘narrative’ for a reader whose identity she did not know. Why would she write at such length and in such detail if she did not know who would read her account? This is clearly a fictional sleight-of-hand on Dickens’s part. But it is one which most readers will be prepared to accept on the principle of ‘suspension of disbelief”.

The ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ is a term coined by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1817 which suggests that if a writer can provide sufficient reasons for doing so, readers would be prepared to overlook or suspend judgement concerning any implausibilities in the story.

But a more significant weakness is that Esther at some points begins to manipulate the novel’s dramatic suspense in a manner that does not fit logically with someone making a record of events. For instance, when Lady Dedlock reveals that she is Esther’s mother, she gives Esther a letter explaining her origins. But Esther only records part of the letter’s contents, remarking that “What more the letter told me, needs not to be repeated here. It has its own times and places in my story”.

Esther is supposed to be a character in the novel, but here she is behaving as an agent in the manner of its composition. In other words she is acting as an author, manipulating the revelation of information to create dramatic interest and tension. This takes her outside the limitations of a character participating in the events of the novel, to that of a contributing author of events. There is no other reason why she should withhold this information.

When a first person narrator takes up an imaginary pen to record the events of a drama, they are normally already in possession of all the facts in the case – so there can be no excuse for concealing any of them from the reader. The only exception to this convention of fictionality is if the first person account is in the form of a diary – where the reader is prepared to believe that the first person diarist only knows about events up to the point of their being recorded.

Bleak House falls between these two modes of narration. Esther creates for the most part a ‘diary’ of events in which she participates. But when she witholds information she has been given for what is clearly a purpose of creating dramatic suspense – this is Dickens rupturing the pact of ‘suspended disbelief’ between the reader and the author.

For a fictional character to suddenly become conscious of the narrative in which they play a part is not a permissible device on the part of the author. It is breaking the conventions of fictional narratives. However, Bleak House is such a huge novel, packed with characters, dramatic events, and serious topics, that many readers are likely to overlook this weakness. However, it has to be said that ‘Esther’s Narrative’ has given rise to enormous amounts of comment in the critical comment on the novel.

Dickens also seems to get the two modes of narration mixed up at times. At one point there is a scene in Vholes’ office [Ch.51] where only he and Woodcourt are present. Their thoughts and feelings, and even the tone of their voices are accurately presented in typical omniscient third person narrative mode. Yet the scene turns out to be part of Esther’s narrative. She is giving an account of events at which she was not present and could not possibly know in such detail.

The Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov (in his Lectures on Literature) observes that Esther’s literary style starts in a girlish manner, but then gradually incorporates a number of Dickens’s own stylistic mannerisms:

Esther and the author more or less grow accustomed to their different points of view as reflected in their styles. Dickens with all kinds of musical, humorous, metaphorical, oratorical, booming effects and breaks in style on the one hand, and Esther, on the other, starting chapters with flowing conservative phrases. But … when the whole estate is found to have been absorbed by the costs, Dickens at last merges almost completely with Esther. Stylistically the whole book is a gradual sliding into the matrimonial state between the two. And when they insert word pictures or render conversations, there is no difference between them.

Money and Labour

There is a sub theme in the novel of selfishness and gross egotism coupled with either acquisitiveness or living off other people’s labour – in other words a dysfunctional connection with the world of labour and capital. This extends to individuals, to families, to society in general, and even to populations overseas.

The elder Turveydrop, master of ‘Deportment’, is completely idle and sponges off his own son. When the younger ‘Prince’ Turveydrop wishes to marry Caddy Jellyby, his father only reluctantly consents with the sophistry that he will make no claim upon them except to be housed, dressed, and fed for the rest of his life at their expense.

Horace Skimpole elevates idleness and self-interested sponging off others into a solipsistic philosophy. He even claims that the debts he accrues are a positive example of keeping debt-collectors in work. Indeed, it is one of the mysteries of the novel why John Jarndyce should tolerate this social parasite to the extent that he does. For the majority of the novel Jarndyce makes excuses for him, explains away his irresponsibility, and treats him at his own word as a ‘child’.

Even the slightly macabre Smallweeds are motivated by a combination of meanness and acquisition. They are money-lenders who hide behind the pretence that the exorbitant rates they charge are determined by ‘higher powers’ for whom they are acting in the City.

Richard Carstone is also linked to this theme. He is mesmerised by the prospects of an inheritance-to-come from the Jarndyce case. He cannot settle and apply himself to a career, because he imagines he will become very rich ‘any day soon’. So he is lured into moral decline by the promise of unearned wealth. And he not only lives on the kindness of John Jarndyce, but he also runs up debts he cannot pay because of his self-indulgent way of life. Even when he marries Ada, it is her money he squanders shortly before his death at the end of the court case.

John Jarndyce is also related to this theme – but only in the sense that he represents its opposite. He is exceptionally generous to everybody. He takes on the role of guardian to Esther when she is regarded as an orphan; he supports his two cousins, Ada and Richard; and he even provides a house for Allan Woodcourt when he marries Esther. His generosity of spirit is undiminished even when people such as Skimpole and Richard are frittering away the financial support he has provided for them.

But therein lies a problem – because we are not told the source of his lavish income. He is a party to the contested will in the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, though he chooses to disattend to the Chancery proceedings, and he does not appear to be affected by its outcome. He must therefore have a source of income separate from inherited wealth which is at the root of the dispute – but we are not told what this is.

Bleak House – study resources

![]() Bleak House – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

Bleak House – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Bleak House – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

Bleak House – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() Bleak House – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

Bleak House – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Bleak House – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

Bleak House – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() Bleak House – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

Bleak House – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Complete Works of Charles Dickens – Kindle edition

The Complete Works of Charles Dickens – Kindle edition

![]() Charles Dickens – biographical notes

Charles Dickens – biographical notes

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens – Amazon UK

Bleak House – plot summary

Ch. 1 – In Chancery Late autumn in the Court of Chancery in London: the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce has been going on so long that nobody even understands what it is all about any more.

Ch. 2 – In Fashion The fashionable Lady Dedlock has become bored on her Lincolnshire estate and is in London prior to her departure to Paris. Mr Tulkinghorn calls to report that Jarndyce versus Jarndyce has been in court. He reads from reports to Sir Leicester Dedlock, but Lady Deadlock feels ill land has to retire.

Ch. 3 – A Progress Esther’s narrative recounts her being raised by a severe godmother, and her knowing nothing of her parents. On her godmother’s death Kenge arranges for her transfer to Miss Donny’s finishing school. Six years later Jarndyce arranges for her to become a companion to Ada Clare.

Ch. 4 – Telescopic Philanthropy Esther, Ada, and Richard Carstone go to the ‘philanthropist’ Mrs Jellyby’s house where everything is in a state of dirt and disorder. Esther comforts some of Mrs Jellyby’s neglected children, especially the disaffected elder daughter Caroline (Caddy).

Ch. 5 – A Morning Adventure On a walk next morning Esther, Ada, and Richard meet the old lady from the Court. She takes them to meet the rag and bone collector Krook, who is her landlord, who recounts the suicide of Tom Jarndyce and writes mysteriously on the wall.

Ch. 6 – Quite at Home Esther, Ada, and Richard then travel to Bleak House, where they are welcomed by their friendly benefactor John Jarndyce, who quizzes them about the Jellyby family. He then introduces them to the self-deceiving sponger Horace Skimpole, who when he is about to be arrested allows Esther and Richard to pay off his debts.

Ch. 7 – The Ghost’s Walk The housekeeper Mrs Rouncewell is at Chesney Wold with her grandson Watt when Guppy arrives to look over the house (on behalf of Kenge and Carboy)). He seems to recognise Lady Dedlock in a portrait painting. Mrs Rouncewell tells the story of the Civil War differences in the family and a previous Lady Dedlock who put a curse on the house.

Ch. 8 – Concerning a Multitude of Sins John Jarndyce confides in Esther, giving her a (rather vague) account of the great court case and putting his trust in her. Esther learns that he is besieged by charitable ladies seeking funds for their enthusiasms. They are visited by the officious Mrs Pardiggle who takes them on an intrusive visit to a brickmaker’s cottage. When Mrs Pardiggle is dismissed, they discover a child is dead.

Ch. 9 – Signs and Tokens Bleak House is visited by the boisterous Lawrence Boythorn, who relates his boundary dispute with Sir Leicester Dedlock. Mr Guppy arrives as clerk to Kenge and Carboy, and makes a comic proposal to Esther, with whom he has become smitten after a single meeting. She is ambiguously flustered by the event.

Ch. 10 – The Law-Writer Lawyer Tulkinghorn visits legal stationer Snagsby to identify the copyist of a legal document in the Jarndyce case. Snagsby takes him to meet ‘Nemo’ who is lodging at Krook’s rag and bottle shop. Nemo lives in utter destitution and is an opium addict

Ch. 11 – Our Dear Brother When Tulkinghorn enters his room, Nemo turns out to be dead from an opium overdose. Nobody knows anything about him, but it seems he might be from a cultivated background. Tulkinghorn keeps a close eye on events. A coroner’s inquest is held in a local ale house. The evidence of the only person who knew him (Jo, a crossing sweeper) is not admitted as acceptable.

Ch. 12 – On the Watch The Dedlocks leave Paris, bored. Sir Leicester receives a letter from Tulkinghorn mentioning Nemo’s affidavit – which discomforts Lady Dedlock. At Chesney Wold rivalry springs up between Hortense and Rosa, the pretty new lady’s maid. Tulkinghorn arrives to discuss the boundary dispute with Boythorn, but he also reveals the news regarding Nemo.

Ch. 13 – Esther’s Narrative Richard is a dilettante who cannot make up his mind about a future profession. He is also living in the hope of inheriting from the great Jarndyce case and his wards go to London, where Esther is again embarrassed by Guppy’s unwanted attentions.. Richard is finally apprenticed to medical man Bayham Badger, whose wife has been married twice before.Ada and Richard make their love known to Esther, then to Jarndyce, who gives them his blessing.

Ch. 14 – Deportment Richard is still hoping to inherit money. Esther is visited by Caddy Jellyby, who complains that her family is almost bankrupt. She reveals that she is engaged to Prince Turveydrop. They visit the dancing school, run by his vain and idle father. They visit Miss Flite, who believes the money she receives each week is forward payment from the Chancellor himself. Krook arrives and takes an unpleasantly close interest in Jarndyce.

Ch. 15 – Bell Yard Skimpole arrives with the news that Coavinces has died. Jarndyce and his entourage visit a garret where Coavinces’ three small children are barely surviving. They meet a neighbour Gridley (‘the man from Shropshire’) whose entire legacy has been swallowed up in legal costs. In the face of all this poverty and injustice Skimpole argues that everything is for the best, and that because of his own unpaid debts he has provided employment for a debt collector.

Ch. 16 – Tom-all-alone’s Crossing sweeper Jo exists in a state of abject poverty and animal-like ignorance in the slum at Tom-all-alone’s. Lady Deadlock visits Tulkinghorn, then asks Jo to show her all the places associated with Nemo, including where he is buried.

Ch. 17 – Esther’s Narrative Mr and Mrs Badger warn Esther that Richard is not taking his training seriously. When challenged Richard says he wants to take up law. Jarndyce reveals to Esther how he adopted her from her godmother. Allan Woodcourt leaves for India and China.

Ch. 18 – Lady Dedlock Richard moves to lodgings in London, spending extravagantly. Skimpole has his furniture confiscated, and sends the bill to Jarndyce. There is a visit to Lawrence Boythorn at Chesney Wold. Esther sees Lady Dedlock in church and feels disturbed. She meets her again in the park whilst sheltering from a storm and cannot explain a sense of recognition she feels.

Ch. 19 – Moving on The Snagsbys put on tea for the pompous Reverend and Mrs Chadband. Whilst there Jo is cautioned by a constable and reveals his contact with Lady Dedlock. Guppy recognises Mrs Chadband, who brought Esther to Kenge and Carboy’s office.

Ch. 20 – A New Lodger Guppy feels rivalry at having Richard articled at Kenge and Carboy. Guppy and Smallweed take down-and-out Tony Jobling for lunch. Guppy persuades him to become a lodger at Krook’s (in Nemo’s old room) and he finds him a job as a copyist at Snagsby’s.

Ch. 21 – The Smallweed Family The Smallweeds are an eccentric family of undeveloped mean-minded money lenders. Mr George comes to make a repayment. They try to persuade him to take out further loans, and they pretend to be acting as intermediaries for someone more powerful. Mr George goes back to his unprofitable shooting gallery.

Ch. 22 – Mr Bucket Snagsby tells Tulkinghorn about Jo’s story, then goes with Inspector Bucket to Tom-all-alone’s where they encounter scenes of squalor and pestilence. When they bring Jo back to Tulkinghorn’s office, Hortense is dressed as her mistress Lady Dedlock, but Jo’s evidence reveals that this was not the woman he took to Nemo’s grave.

Ch. 23 – Esther’s Narrative Hortense has left Lady Dedlock and wants Esther to take her on as maid, but Esther refuses. Richard has become infatuated with the Jarndyce case, but wants to leave the law and join the Army. He has also amassed debts. Esther helps Caddy Jellyby break the news of her engagement to Mr Turveydrop and Mrs Jellyby.

Ch. 24 – An Appeal Case When it is time for Richard to join the army, Mr Jarndyce insists that it is his last chance at choosing a profession and that he and Ada must break off their engagement. Mr George thinks he recognises Esther, and he reveals that Gridley is one of his customers – and is hiding in the shooting gallery. Esther visits the Court and is dismayed by its procedures. Mr George comes to the Court for Miss Flite. They all assemble at the shooting gallery, and Bucket arrives (disguised as a doctor) to arrest Gridley. But Gridley dies, worn out by his struggles with the Court.

Ch. 25 – Mrs Snagsby sees it all Snagsby is worried that something is wrong, but he does not know what it is. Meanwhile, Mrs Snagsby is also suspicious of him, thinking Jo might be his illegitimate son. Jo is brought before ‘Reverend’ Chadband , who delivers a meaningless catechism upon him.

Ch. 26 – Sharpshooters Mr George and Phil Squod are visited by Smallweed who reveals that Richard has been borrowing money. He has come in search of a sample of writing by Captain Hawdon. Mr George is suspicious, but agrees to go to Tulkinghorn’s office for further information.

Ch. 27 – More Old Soldiers than one Tulkinghorn wants the sample to compare the writing with another document in his possession, but George refuses to co-operate. George goes to seek advice from his old colleague Matthew Bagnet, but the advice (given by his wife) is to steer clear of anything that makes him feel uncomfortable. George returns to Tulkinghorn, who curses him for not producing the evidence.

Ch. 28 – The Ironmaster Volumina Dedlock and other minor ‘cousins’ are at Chesney Wold. Mrs Rouncewell’s son (the Ironmaster) asks Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock for permission to remove Rosa from Chesney Wold in the event of her marrying his son Matt Rouncewell. Sir Leicester is outraged at the very idea.

Ch. 29 – The Young Man Guppy arrives at Dedlock’s London house to see Lady Dedlock. He recounts the list of connections he has established – Esther’s similarity to her; Jo’s connection with her; Nemo’s and Esther’s real name being Hawdon. He has some new documents coming, and his objective is to impress Esther. Lady Dedlock reluctantly agrees to see him again

Ch. 30 – Esther’s Narrative Esther is visited by Mrs Woodcourt who bores everyone about her famous Welsh ancestors and her son Allan, who must not marry beneath his true social station. Esther helps Caddy Jellyby prepare for her wedding, which goes off without incident.

Ch. 31 – Nurse and Patient Charley reports to Esther that Jo is in the neighbourhood. He is on the run, and has some sort of fever. Esther houses him for the night, but in the morning he has disappeared. Charley develops smallpox which she has caught from Jo. Esther nurses her back to health, then contracts the disease herself.

Ch. 32 – The Appointed Time Tony Jobling (aka Weevle) is feeling depressed in Nemo’s old room at Krook’s. He is visited first by Snagsby then by Guppy, who is due to receive Nemo’s letters for copying from Krook (who cannot read) – but not until midnight. The room fills with soot and foul vapours. At midnight they go down and find that Krook is no longer there, having died from ‘spontaneous combustion’.

Ch. 33 – Interlopers There is an inquest at Sol’s Arms. Snagsby appears and wonders if he is guilty of anything, but he is taken away by the ever-suspicious Mrs Snagsby. Old Smallweed appears and reveals that Krook was his wife’s brother. Smallweed has come to ‘secure the property’, with Tulkinghorn as his solicitor. Guppy reports to Lady Dedlock that he no longer has the letters he promised – and he is dismissed out of hand.

Ch. 34 – A Turn of the Screw Mr George receives a demand from Smallweed on a debt in his friend Bagnet’s name. Mr and Mrs Bagnet arrive at the shooting gallery. She reproaches George, who apologises. George and Bagnet go to see Smallweed, asking for leniency in payment. Smallweed throws them out. They then go to Tulkinghorn, where the reception is hostile. But George trades the letter he has in Hawdon’s handwriting for a letter of exemption on Bagnet for the debt.

Ch. 35 – Esther’s Narrative Esther gradually recovers from the smallpox but is left badly disfigured. Richard turns against his guardian Jarndyce. Miss Flite visits and reports on a lady in a veil making enquiries about Esther. She recounts how her family were drawn into the Jarndyce case and all perished. She also recounts news of Allan Woodcourt who has distinguished himself in an Eastern shipwreck.

Ch. 36 – Chesney Wold Esther stays at Chesney Wold at the invitation of Boythorn. She confronts her own disfigurement in the mirror. Walking in the park she meets Lady Dedlock, who reveals that she is her mother. She gives Esther an explanatory letter, only part of which Esther reveals in her narrative.

Ch. 37 – Jarndyce and Jarndyce Richard visits Chesney Wold with Horace Skimpole to plead his case with Esther. He is now indifferent to the Army and still builds all his hopes on the Court case. He believes that Jarndyce should not be trusted. He is also in debt again. His solicitor Vholes arrives and they immediately set off to drive to the Court next day where the Jarndyce case is being heard.

Ch. 38 – A Struggle Esther returns to live at Bleak House. She visits Caddy Jellyby who is assisting her husband and his apprentices at the dancing school. She then consults Guppy, asking him not to look into her background. He agrees, but makes a comical retraction in exaggerated legal terms of his previous proposal of marriage to her (because she is now disfigured).

Ch. 39 – Attorney and Client Richard complains to his solicitor Mr Vholes about the lack of progress in the Jarndyce case. Vholes replies with sophistical excuses and claims that he is ever-vigilant on his client’s behalf. Guppy accompanies Tony Jobling to the Krook house where he is recovering his effects. There is speculation that Nemo’s papers might have escaped the spontaneous combustion fire.

Ch. 40 – National and Domestic The long recess is over. Preparations are under way at Chesney Wold for national elections. Lady Dedlock has not been well. Voters are being bribed and bought off. Tulkinghorn arrives with news of political setbacks for Dedlock, and the housekeeper Mrs Rouncewell’s son and grandson are involved. Tulkinghorn then delivers a thinly disguised story of Lady Dedlock and her child by a former captain lover.

Ch. 41 – In Mr Tulkinghorn’s Room Lady Dedlock immediately visits Tulkinghorn in his room at Chesney World to challenge him regarding his disclosure. She plans to leave Chesney Wold the same night. Tulkinghorn argues that she should consider her husband’s honour and social reputation. He promises to keep her secret for a while longer, and persuades her to stay.

Ch. 42 – In Mr Tulkinghorn’s Chambers Back at his Lincoln’s Inn chambers, Tulkinghorn is met by Snagsby, who complains about being harassed by Hortense. She then appears to complain that Tulkinghorn has not been fair to her. He threatens to report her to the police if she comes anywhere near him or Snagsby again.

Ch. 43 – Esther’s Narrative Esther is oppressed by the need to keep her mother’s identity a secret. She quizzes Jarndyce about Herbert Skimpole, but he defends him. They then visit Skimpole’s house where Jarndyce makes a feeble attempt to talk sense to him about money and responsibility. Skimpole introduces his three vacuous daughters, then leaves with Jarndyce to escape someone whose chairs he has borrowed and ruined. At Bleak House they are visited by Sir Leicester Dedlock, who invites everybody to visit Chesney Wold. Esther reveals to Jarndyce that Lady Dedlock is her mother, and he reveals that Boythorn was engaged to Lady Dedlock’s sister.

Ch. 44 – The Letter and the Answer Next day Jarndyce agrees to support her, then he writes her a letter proposing marriage. Esther feels conflicted by the news. Allan Woodcourt comes back into her thoughts. She plans to write a letter to Jarndyce in reply, but doesn’t. Instead, she tells him that she will marry him.

Ch. 45 – In Trust Vholes arrives with news of Richard’s unpaid debts. Esther goes to visit Richard in Deal. He has just resigned his commission and continues to nurture hopes for success in Court. He receives a letter from Ada offering him her inheritance to pay off his debts. He says he will refuse it. Whilst there Esther meets Allan Woodcourt, recently back from India, and asks him to befriend and help Richard.

Ch. 46 – Stop him! Allan Woodcourt meets Jenny the brickmaker’s wife in Tom-all-alone’s in the early morning. He tends her matrimonial wounds, then chases down Jo who suddenly appears. Jo reveals that he was taken away when in Esther’s care by someone [Bucket] and put into hospital, then given money to stay away.

Ch. 47 – Jo’s Will Woodcourt takes the homeless Jo to Miss Flite, who recommends Mr George as a source of refuge for the boy. Mr George agrees to give him shelter, fuelled by his dislike of Bucket and Tulkinghorn. The penniless Jo asks Snagsby to write his will, and then he dies.

Ch. 48 – Closing in Lady Deadlock reassures Rosa that she likes her but is dismissing her from service at Chesney Wold (to protect her reputation). Mr Rouncewell is summoned and agreement eventually reached with Sir Leicester on Rosa’s dismissal. Tulkinghorn then claims Lady Dedlock has broken their agreement, and threatens to expose her secret to her husband. Following this, Tulkinghorn is shot through the heart by someone unknown.

Ch. 49 – Dutiful Friendship Mr Bagnet is celebrating his wife’s birthday with the family. He cooks a dinner which is almost inedible. Mr George arrives in low spirits after the death of Jo. Then Mr Bucket arrives, flatters Mrs Bagnet, and makes a big fuss of the children. But when Bucket and Mr George leave, the detective arrests him as a suspect for the murder of Tulkinghorn.

Ch. 50 – Esther’s Narrative Caddy Jellyby falls ill and is nursed devotedly by Esther. Jarndyce recommends Woodcourt as a doctor for her. Esther feels that these events cast something of a shadow over her relationship with Ada.

Ch. 51 – Enlightened Woodcourt goes to see Richard who is still in thrall to Vholes and the Chancery case. He claims he is acting for Ada’s interests in the case, as well as for his own. Esther and Ada go to visit Richard, where Ada reveals the she has been secretly married to him for the last two months. Esther returns to tell Jarndyce, who has already guessed as much.

Ch. 52 – Obstinacy Woodcourt brings news of Mr George’s arrest to Bleak House. They all visit the jail and try to persuade Mr George to defend himself. But he stubbornly refuses to do so, and is particularly critical of lawyers. Mr Bagnet arrives with his wife, who reproaches Mr George for being so stubborn. Esther feels uncomfortable because of her connection with Lady Dedlock. Afterwards Mrs Bagnet discloses that Mr George has an elderly mother still alive, and she sets off for Lincolnshire to retrieve her.

Ch. 53 – The Track Mr Bucket attends the funeral of Tulkinghorn, then goes to the Dedlock town house. He is interviewed by Sir Leicester, who offers him financial support in pursuit of the crime. Bucket is meanwhile in receipt of letters pointing suspicion at Lady Dedlock. Bucket also quizzes a footman on Lady Dedlock’s habits and her behaviour on the night of the murder.

Ch. 54 – Springing a Mine Next morning Bucket confronts Sir Leicester and reveals the secret history of Lady Deadlock’s lover and the fact that Tulkinghorn had been spying on her. Suddenly Grandfather Smallweed and the Chadbands arrive, trying to extort money for their knowledge of the ‘secret’ and in search of Lady Dedlock’s letters, which are in Bucket’s possession. They are dismissed, and Bucket produces the culprit – Hortense – and spells out the case against her, based on what he claims is her hatred of Lady Dedlock.

Ch. 55 – Flight Mrs Bagnet returns from Lincolnshire with Mrs Rouncewell, who turns out to be Mr George’s mother. They visit him in prison where he begs his mother’s forgiveness for his wayward past and filial neglect. Mrs Rouncewell then goes to Lady Dedlock and asks her to do anything she can to help her son. She also gives her a letter which contains an account of the murder, followed by Lady Dedlock’s name and the charge ‘Murderess’. Guppy calls to warn her about Smallweed and the still-extant letters. Lady Dedlock writes her husband a letter claiming her innocence, then escapes from the house.

Ch. 56 – Pursuit Sir Leicester has a stroke brought on by the shock of all these revelations. When he recovers he cannot speak, but sets Bucket in pursuit of his wife. Bucket seeks out Esther to accompany him, fearing that Lady Dedlock might be contemplating suicide.

Ch. 57 – Esther’s Narrative Esther is collected by Bucket, and they go in search of Lady Dedlock. First to Limehouse, then along the river, and then to St Albans and Bleak House. They go to the brickmakers’ cottage where they discover that she has passed through the night before. They press on, but find nothing – so Bucket suddenly decides to backtrack to London.

Ch. 58 – A Wintry Day and Night News of Lady Dedlock’s disappearance spreads through fashionable society. Sir Leicester is still recuperating. He asks Mrs Rouncewell to produce her prodigal son George – and the meeting seems to be beneficial to him, since he knew George as a child. He declares to the household that he has no quarrel at all with Lady Dedlock, who still does not appear, even though the house is being prepared for her return.

Ch. 59 – Esther’s Narrative Esther and Bucket arrive back in London in the early hours of the morning. They meet Woodcourt and go to Snagsby’s where a letter written by Lady Dedlock is recovered from Gusta, who has had a fit. She recounts how Lady Dedlock has asked for directions to the Burial Ground. When they get there Esther finds her mother dead at the gates, dressed in poor Jenny’s clothes.

Ch. 60 – Perspective Jarndyce engineers more contact with Woodcourt, who has prospects of a modest position in Yorkshire. Richard is ever more enmeshed with the Court, and is spending Ada’s money. Vholes confirms that Richard is in a bad way. Ada confesses her fears to Esther, and reveals that she is having a baby.

Ch. 61 – A Discovery Esther pleads with Skimpole to stay away from Richard and Ada, to which he agrees. But he breaks his promise and is cut off by Jarndyce. At this point he disappears from the story and is said to die five years later. Woodcourt gets his job in Yorkshire and declares his undying love to Esther, who does not tell him that she is supposed to be marrying Jarndyce.

Ch. 62 – Another Discovery Next day Esther renews her promise to marry Jarndyce. Bucket arrives with Smallweed who has found a Jarndyce will amongst Krook’s old papers. They take the will to Kenge, who tells them it gives Jarndyce less money and Richard and Ada more. Jarndyce continues to want nothing to do with the matter.

Ch. 63 – Steel and Iron Mr George travels north and searches out his brother the successful Ironmaster. He is very well received, but wishes to be written out of his mother’s will because of his previous behaviour. He brother suggests he should not offend their mother, but will the inheritance to someone else – which he does. He turns down the offer of a job, preferring to work as a groom to Sir Leicester Dedlock.

Ch. 64 – Esther’s Narrative Esther is preparing for her marriage when she is summoned to Yorkshire by Jarndyce. He has organised a cottage home for Woodcourt modelled on Bleak House, and renounces his claim on Esther in favour of the doctor. Back in St Albans, Guppy calls with his mother and renews his proposal of marriage to Esther (now that he thinks she will be rich). Mrs Guppy is vigorously offended when it is refused.

Ch. 65 – Beginning the World The Jarndyce case finally comes to court. Esther and Woodcourt attend, finding all the lawyers and court attendants laughing at the outcome. It turns out that the whole estate has been swallowed up in costs. Richard is devastated and falls ill, but vows to start a new life. However, he dies amongst his friends.

Ch. 66 – Down in Lincolnshire At Chesney Wold, Sir Leicester is an invalid who has retreated from life in the care of Mr George. The house is largely closed up, and Lady Dedlock’s ashes are in the family mausoleum in the grounds.

Ch. 67 – The Close of Esther’s Narrative Ada has a baby boy who is given his father’s name. She is invited to live with Jarndyce. Esther has two children, and Woodcourt is a well-respected local doctor.

Bleak House – characters

| Sir Leicester Dedlock | a baronet, but not a peer (67) |

| Lady Honoria Dedlock | his very fashionable wife (47) |

| Tulkinghorn | a ruthless and single-minded lawyer |

| Esther Summerson | an ‘orphan’ |

| ‘Conversation’ Kenge | a Chancery lawyer who likes to hear himself talk |

| Miss Barbary | Esther’s severe godmother (actually her aunt) |

| John Jarndyce | Esther’s guardian, Ada’s cousin |

| Ada Clare | an orphan, cousin to John Jarndyce (17) |

| Richard Carstone | an orphan, Ada’s cousin (19) |

| Mrs Jellyby | a ‘philanthropist’ obsessed with Africa |

| Mr Jellyby | her husband, a nonentity |

| Mr Quale | an acolyte to Mrs Jellyby |

| Caroline (Caddy) Jellyby | their eldest daughter, befriended by Esther |

| Miss Flite | eccentric elderly ‘suitor’ in Jarndyce case |

| Horace Skimpole | a professional layabout and sponger |

| Krook | rag and bottle shop owner, and landlord |

| Mrs Rouncewell | housekeeper to the Dedlocks |

| Mr George (Rouncewell) | her son, an ex-soldier and vagabond, keeper of the shooting gallery |

| Mrs Pardiggle | an imperious charity scrounger |

| Lawrence Boythorn | outspoken school friend of Jarndyce, neighbour of Dedlock |

| Mr Snagsby | a mild law stationer |

| Mrs Snagsby | his wife, a jealous termagant |

| Augusta (Gusta) | their assistant, given to fits |

| Rosa | pretty trainee at the Dedlock house |

| Hortense | acerbic French lady’s maid to Lady Dedlock |

| Bayham Badger | a medical man |

| Mrs Badger | his wife, who lives through her two previous husbands |

| Mr Turveydrop | an idle, pompous model of ‘deportment’ |

| Prince Turveydrop | his son, a dancing instructor |

| Allan Woodcourt | a young doctor |

| Inspector Bucket | a detective with a flattering and sardonic manner |

| Phil Squod | Mr George’s disfigured assistant |

| ‘Nemo’ | a law copyist and opium addict, (actually Captain Hawdon, Lady Dedlock’s lover and Esther’s father) |

| William Guppy | clerk at Kenge and Carboy, suitor to Esther |

| Mr Gridley | ‘the man from Shropshire’, and suitor in the Jarndyce case who dies |

Criticism

![]() Susan Shatto, The Companion to ‘Bleak House’, London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

Susan Shatto, The Companion to ‘Bleak House’, London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

![]() George Ford and Sylvere Monod (eds) Bleak House, Norton Critical Editions, 1977.

George Ford and Sylvere Monod (eds) Bleak House, Norton Critical Editions, 1977.

![]() A.E.Dyson (ed), Bleak House: A Casebook, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1969.

A.E.Dyson (ed), Bleak House: A Casebook, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1969.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Interpretations of Bleak House, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1987.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Interpretations of Bleak House, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1987.

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Bleak House, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1987.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Bleak House, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1987.

![]() Grahame Smith, Charles Dickens: Bleak House, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1974.

Grahame Smith, Charles Dickens: Bleak House, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1974.

![]() Graham Storey, Bleak House, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Graham Storey, Bleak House, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

![]() Jakob Korg (ed), Twentieth Century Interpretations of Bleak House, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1968.

Jakob Korg (ed), Twentieth Century Interpretations of Bleak House, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1968.

Further reading

Biography

![]() Peter Ackroyd, Dickens, London: Mandarin, 1991.

Peter Ackroyd, Dickens, London: Mandarin, 1991.

![]() John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens, Forgotten Books, 2009.

John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens, Forgotten Books, 2009.

![]() Edgar Johnson, Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph, Little Brown, 1952.

Edgar Johnson, Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph, Little Brown, 1952.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Dickens: A Biography, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Fred Kaplan, Dickens: A Biography, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

![]() Frederick G. Kitton, The Life of Charles Dickens: His Life, Writings and Personality, Lexden Publishing Limited, 2004.

Frederick G. Kitton, The Life of Charles Dickens: His Life, Writings and Personality, Lexden Publishing Limited, 2004.

![]() Michael Slater, Charles Dickens, Yale University Press, 2009.

Michael Slater, Charles Dickens, Yale University Press, 2009.

Criticism

![]() G.H. Ford, Dickens and His Readers, Norton, 1965.

G.H. Ford, Dickens and His Readers, Norton, 1965.

![]() P.A.W. Collins, Dickens and Crime, London: Palgrave, 1995.

P.A.W. Collins, Dickens and Crime, London: Palgrave, 1995.

![]() Philip Collins (ed), Dickens: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1982.

Philip Collins (ed), Dickens: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1982.

![]() Jenny Hartley, Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women, London: Methuen, 2009.

Jenny Hartley, Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women, London: Methuen, 2009.

![]() Andrew Sanders, Authors in Context: Charles Dickens, Oxford University Press, 2009.

Andrew Sanders, Authors in Context: Charles Dickens, Oxford University Press, 2009.

![]() Jeremy Tambling, Going Astray: Dickens and London, London: Longman, 2008.

Jeremy Tambling, Going Astray: Dickens and London, London: Longman, 2008.

![]() Donald Hawes, Who’s Who in Dickens, London: Routledge, 2001.

Donald Hawes, Who’s Who in Dickens, London: Routledge, 2001.

Other works by Charles Dickens

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

Charles Dickens – web links

![]() Charles Dickens at Mantex

Charles Dickens at Mantex

Biographical notes, book reviews, tutorials and study guides, free eTexts, videos, adaptations for cinema and television, further web links.

![]() Charles Dickens at Wikipedia

Charles Dickens at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary techniques, his influence and legacy, extensive bibliography, and further web links.

![]() Charles Dickens at Gutenberg

Charles Dickens at Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts of the major works in a variety of formats.

![]() Dickens on the Web

Dickens on the Web

Major jumpstation including plots and characters from the novels, illustrations, Dickens on film and in the theatre, maps, bibliographies, and links to other Dickens sites.

![]() The Dickens Page

The Dickens Page

Chronology, eTexts available, maps, filmography, letters, speeches, biographies, criticism, and a hyper-concordance.

Charles Dickens at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of the major novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages

![]() A Charles Dickens Journal

A Charles Dickens Journal

An old HTML website with detailed year-by-year (and sometimes day-by-day) chronology of events, plus pictures.

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Dickens

Hyper-Concordance to Dickens

Locate any word or phrase in the major works – find that quotation or saying, in its original context.

![]() Dickens at the Victorian Web

Dickens at the Victorian Web

Biography, political and social history, themes, settings, book reviews, articles, essays, bibliographies, and related study resources.

![]() Charles Dickens – Gad’s Hill Place

Charles Dickens – Gad’s Hill Place

Something of an amateur fan site with ‘fun’ items such as quotes, greetings cards, quizzes, and even a crossword puzzle.

© Roy Johnson 2015

More on Charles Dickens

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

3. This can mean anything from a work’s particular vocabulary, sentence construction, and imagery, to the themes that are being dealt with, the way in which the story is being told, and the view of the world that it offers. It involves almost everything from the smallest linguistic items to the largest issues of literary understanding and judgement.

3. This can mean anything from a work’s particular vocabulary, sentence construction, and imagery, to the themes that are being dealt with, the way in which the story is being told, and the view of the world that it offers. It involves almost everything from the smallest linguistic items to the largest issues of literary understanding and judgement. Studying Fiction

Studying Fiction

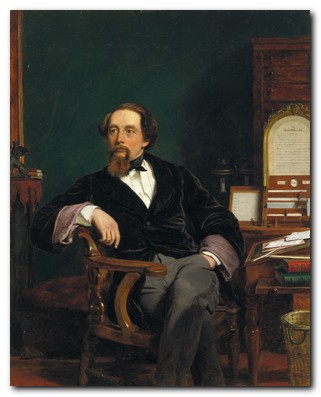

1812. Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth. His father was a clerk in naval pay office: hard-working but unable to live within income. Several brothers and sisters.

1812. Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth. His father was a clerk in naval pay office: hard-working but unable to live within income. Several brothers and sisters. The Oxford Companion to Dickens offers in one volume a lively and authoritative compendium of information aboutDickens: his life, his works, his reputation and his cultural context. In addition to entries on his works, his characters, his friends and places mentioned in his works, it includes extensive information about the age in which he lived and worked.These are the people, events and institutions which provided the context for his work; the houses in which he lived; the countries he visited; the ideas he satirized; the circumstances he responded to; and the culture he participated in. The companion thus provides a synthesis of Dickens studies and an accessible range of information.

The Oxford Companion to Dickens offers in one volume a lively and authoritative compendium of information aboutDickens: his life, his works, his reputation and his cultural context. In addition to entries on his works, his characters, his friends and places mentioned in his works, it includes extensive information about the age in which he lived and worked.These are the people, events and institutions which provided the context for his work; the houses in which he lived; the countries he visited; the ideas he satirized; the circumstances he responded to; and the culture he participated in. The companion thus provides a synthesis of Dickens studies and an accessible range of information.

Dombey and Son (1847-48) is Dickens’ version of the King Lear story, in which Dombey, the proud and successful head of a shipping company, loses his son, wife, and daughter because of neglect and his lack of sympathy towards them. Even his second wife is driven into the arms of his villainous business manager – with disastrous results. Eventually his empire collapses, and he lives on in tragic desolation – until his daughter Florence returns and finds a way back to his heart. This is the first of Dickens’ great and powerful masterpieces.

Dombey and Son (1847-48) is Dickens’ version of the King Lear story, in which Dombey, the proud and successful head of a shipping company, loses his son, wife, and daughter because of neglect and his lack of sympathy towards them. Even his second wife is driven into the arms of his villainous business manager – with disastrous results. Eventually his empire collapses, and he lives on in tragic desolation – until his daughter Florence returns and finds a way back to his heart. This is the first of Dickens’ great and powerful masterpieces. David Copperfield (1849-50) is a thinly veiled autobiography, of which Dickens said ‘Of all my books, I like this the best’. As a child David suffers the loss of both his father and mother. He endures bullying at school and a life of poverty when he goes to work. The book is packed with memorable characters such as Mr Micawber, the fawning Uriah Heep, and the earth-mother figure Clara Peggotty. The plot involves Dickens’ recurrent topics of thwarted romance, financial insecurity and misdoings, and the terrible force of the legal system which haunted him all his life.

David Copperfield (1849-50) is a thinly veiled autobiography, of which Dickens said ‘Of all my books, I like this the best’. As a child David suffers the loss of both his father and mother. He endures bullying at school and a life of poverty when he goes to work. The book is packed with memorable characters such as Mr Micawber, the fawning Uriah Heep, and the earth-mother figure Clara Peggotty. The plot involves Dickens’ recurrent topics of thwarted romance, financial insecurity and misdoings, and the terrible force of the legal system which haunted him all his life. Little Dorrit (1855-57) features Dickens’ recurrent themes of prison, debt, and the negative effects of wealth. William Dorrit and his daughter Amy have been paupers for so long that they actually live in the Marshalsea debtor’s prison. When he is suddenly released because of an inheritance, his place is taken by the middle-aged hero Arthur Clenham when he falls on hard times. Amy is devoted to them both. There is also a murky sub-plot involving doubtful parentage, a mysterious secret, and a villain with two names. Also includes a satirical critique of nineteenth century government bureaucracy in his depiction of the Circumlocution Office. Another of the greatest of Dickens’ works.

Little Dorrit (1855-57) features Dickens’ recurrent themes of prison, debt, and the negative effects of wealth. William Dorrit and his daughter Amy have been paupers for so long that they actually live in the Marshalsea debtor’s prison. When he is suddenly released because of an inheritance, his place is taken by the middle-aged hero Arthur Clenham when he falls on hard times. Amy is devoted to them both. There is also a murky sub-plot involving doubtful parentage, a mysterious secret, and a villain with two names. Also includes a satirical critique of nineteenth century government bureaucracy in his depiction of the Circumlocution Office. Another of the greatest of Dickens’ works. A Tale of Two Cities (1859) was Dickens’ account of the French Revolution – with the story switching between London and Paris. It views the causes and effects of the Revolution from an essentially private point of view, showing how personal experience relates to public history. The characters are fictional, and their political activity is minimal, yet all are drawn towards the Paris of the Terror, and all become caught up in its web of suffering and human sacrifice. The novel features the famous scene in which wastrel barrister Sydney Carton redeems himself by smuggling the hero out of prison and taking his place on the scaffold. The novel ends with the memorable lines: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known.”

A Tale of Two Cities (1859) was Dickens’ account of the French Revolution – with the story switching between London and Paris. It views the causes and effects of the Revolution from an essentially private point of view, showing how personal experience relates to public history. The characters are fictional, and their political activity is minimal, yet all are drawn towards the Paris of the Terror, and all become caught up in its web of suffering and human sacrifice. The novel features the famous scene in which wastrel barrister Sydney Carton redeems himself by smuggling the hero out of prison and taking his place on the scaffold. The novel ends with the memorable lines: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known.” Great Expectations (1860-61) traces the adventures and moral development of the young hero Pip as he rises from humble beginnings in a village blacksmith’s. Eventually, via good connections and a secret benefactor, he becomes a gentleman in fashionable London – but loses his way morally in the process and disowns his family. Fortunately he is surrounded by good and loyal friends who help him to redeem himself. Plenty of drama is provided by a spectacular fire, a strange quasi-sexual attack, and the chase of an escaped convict on the river Thames. There are a number of strange psycho-sexual features to the characters and events, and the novel has two subtly different endings – both adding ambiguity to the love interest between Pip and the beautiful Stella.

Great Expectations (1860-61) traces the adventures and moral development of the young hero Pip as he rises from humble beginnings in a village blacksmith’s. Eventually, via good connections and a secret benefactor, he becomes a gentleman in fashionable London – but loses his way morally in the process and disowns his family. Fortunately he is surrounded by good and loyal friends who help him to redeem himself. Plenty of drama is provided by a spectacular fire, a strange quasi-sexual attack, and the chase of an escaped convict on the river Thames. There are a number of strange psycho-sexual features to the characters and events, and the novel has two subtly different endings – both adding ambiguity to the love interest between Pip and the beautiful Stella. The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory.