Leonard and Virginia Woolf and the Hogarth Press

John Lehmann joined the Hogarth Press as a trainee manager in 1931 when it was in the full flush of its first success. Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse had just been published, as well as T.S.Eliot’s The Waste Land and Katherine Mansfield’s Prelude. This was to be the first of two periods of engagement with the Press, the second of which lasted until 1946. Thrown to the Woolfs his account of publishing and the literary world of the 1930’s is dominated by the figure of Leonard Woolf, whose own account of the Hogarth Press in his Autobiography confirms almost all of what Lehmann says – though they differed over issues of policy.

It’s a rather unglamorous world of working strict office hours in crowded basement rooms, with “a ramshackle lavatory, in which old Hogarth Press galley proofs were provided as toilet paper”. He was delighted to be mixing with some of the major figures of the modernist period, as well as the up-and-coming writers of the day. There are sketches of writers of the period with whom Lehmann dealt: Michael Roberts, William Plomer, and Christopher Isherwood, whom he introduced to the Press as the Great Hope of English Fiction (which people believed at the time).

It’s a rather unglamorous world of working strict office hours in crowded basement rooms, with “a ramshackle lavatory, in which old Hogarth Press galley proofs were provided as toilet paper”. He was delighted to be mixing with some of the major figures of the modernist period, as well as the up-and-coming writers of the day. There are sketches of writers of the period with whom Lehmann dealt: Michael Roberts, William Plomer, and Christopher Isherwood, whom he introduced to the Press as the Great Hope of English Fiction (which people believed at the time).

He does his best to be fair to Leonard Woolf, and his portrait corresponds accurately to that which one gains from other accounts, including Woolf’s own:

Leonard himself was, in general, cool and philosophical about the ups and downs of publishing: his fault was in allowing trifles to upset him unduly. A penny, a halfpenny that couldn’t be accounted for in the petty cash at the end of the day would send him into a frenzy that often approached hysteria… On the other hand, if a major setback occurred – a new impression, say, of a book that was selling fast lost at sea on its way from the printers in Edinburgh – he would display a sage-like calm, and shrug his shoulders.

It’s quite obvious from his account that although he was being employed in commerce as a publisher’s assistant, to write adverts, promote sales, and check proofs, his heart was set on being a ‘poet’ himself. The tensions he felt with Leonard Woolf became more serious, and within two years of securing what he at first thought of as his dream job, he gave in his notice and left under a very dark cloud.

He then gives an account of his wanderings in central Europe, inspired by Rilke’s notion that “In order to write a single verse, one must see many cities” (not having read Emily Dickinson, it would seem). Much of this part of the story revolves around Christopher Isherwood and Lehmann’s efforts in publishing the collection New Writing. But in 1938, having made up with the Woolfs, he bought out Virginia’s share of the Press and rejoined it as manager and full partner.

The theme then becomes ‘How does one run a publishing company during a war?’. The odd thing is that despite paper rationing, despite being bombed out of its premises in Mecklenburgh Square, and despite having to transfer the Press and its business to Letchworth, sales rose, because of general shortages:

Books that in peacetime, when there was an abundance of choice, would have sold only a few copies every month, were snapped up the moment they arrived in the shops.

Priority was given to keeping Virginia Woolf’s works in print even after her death, as well as the works of Sigmund Freud which the Press had started to publish. Other writers whose work appeared around this time were Henry Green, Roy Fuller, and William Sansom.

However, following Viginia’s death in 1941, there remained only two essential decision makers on policy. Without her casting vote, the differences between them grew wider and led to clashes. Lehmann wanted to publish Saul Bellow and Jean Paul Sartre, but Leonard said ‘No’. There were also misunderstandings about income tax returns and the foreign rights to Virginia’s work.

When the final split between them came about, Leonard solved the problem by persuading fellow publisher Ian Parsons of Chatto and Windus to buy out John Lehmann’s share. Parsons was the husband of Trekkie Parsons, who lived with Leonard during the week and with her husband at weekends – so as well as sharing a wife, they became business partners.

John Lehmann eventually went on to found his own publishing company, and the Hogarth Press was absorbed into Chatto and Windus on Leonard’s death in 1969. This is an interesting account of their joint efforts – partisan, but reasonable and humanely argued.

For literary historians it’s an interesting account of English culture and letters in the 1930s and the war years. And it’s also a fascinating glimpse into the world of commercial publishing. Anyone who wants to make judgments about the rights and wrongs in the disputes between the principals should also read Leonard Woolf’s excellent Autobiography.

© Roy Johnson 2000

John Lehmann, Thrown to the Woolfs, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1978, pp.164, ISBN 0030521912

More on Leonard Woolf

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

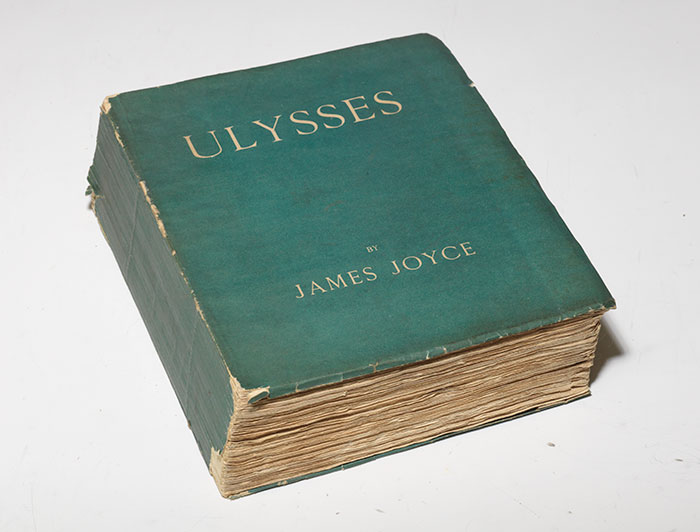

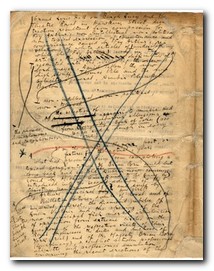

One factor which complicates the textual history of the novel is that Joyce continued working on it, even after it had been published. The printer in Dijon had made errors; Ezra Pound had made cuts and changes to the episodes in circulation via magazines, and Joyce revised multiple copies of his work which had been produced by non-professional typists from his near-illegible handwritten manuscripts.

One factor which complicates the textual history of the novel is that Joyce continued working on it, even after it had been published. The printer in Dijon had made errors; Ezra Pound had made cuts and changes to the episodes in circulation via magazines, and Joyce revised multiple copies of his work which had been produced by non-professional typists from his near-illegible handwritten manuscripts. The most spectacular of these attempts was that piloted by the German scholar Hans Walter Gabler, who proposed to ‘recover’ the original text by comparing surviving manuscripts, corrected proofs, and existing editions. He produced what was called a synoptic version, which was issued as Ulysses: The Corrected Text in 1986. This was designed to put an end to all uncertainties regarding the accuracy of the text.

The most spectacular of these attempts was that piloted by the German scholar Hans Walter Gabler, who proposed to ‘recover’ the original text by comparing surviving manuscripts, corrected proofs, and existing editions. He produced what was called a synoptic version, which was issued as Ulysses: The Corrected Text in 1986. This was designed to put an end to all uncertainties regarding the accuracy of the text.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

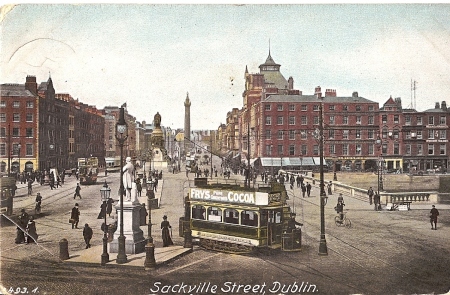

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return. Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad Nostromo

Nostromo The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent

Serge was arrested in 1933, held in solitary confinement, and interrogated endlessly, accused of ‘crimes’ based on the confessions of others which the GPU had actually written. Refusing to co-operate with his captors, he was exiled to Orenberg on the borders of Kazakhstan. He lived there with his son Vlady for the next three years, cold, hungry, and under constant surveillance – but at least free to write. He produced Les Hommes perdus a novel about pre-war French anarchists, and La Tourmente, a sequel to Conquered City. He despatched several copies to Romain Rolland for publication in Paris, but they were ‘lost’ in the post. Ironically, the Post Office was obliged to compensate him for each loss, and he earned ‘as much as a well-paid technician’. He shared the money he earned and the support he received from western Europe with his fellow exiles – on one occasion dividing a single olive with his fellow inmates, who had never tasted one before.

Serge was arrested in 1933, held in solitary confinement, and interrogated endlessly, accused of ‘crimes’ based on the confessions of others which the GPU had actually written. Refusing to co-operate with his captors, he was exiled to Orenberg on the borders of Kazakhstan. He lived there with his son Vlady for the next three years, cold, hungry, and under constant surveillance – but at least free to write. He produced Les Hommes perdus a novel about pre-war French anarchists, and La Tourmente, a sequel to Conquered City. He despatched several copies to Romain Rolland for publication in Paris, but they were ‘lost’ in the post. Ironically, the Post Office was obliged to compensate him for each loss, and he earned ‘as much as a well-paid technician’. He shared the money he earned and the support he received from western Europe with his fellow exiles – on one occasion dividing a single olive with his fellow inmates, who had never tasted one before.