tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

Jacob’s Room (1922) was the first of Virginia Woolf’s novels that she published herself, as co-founder of the Hogarth Press. She knew that the form of literary experimentation she contemplated would not be welcome by other publishers, so she took the opportunity to push her radical approach to narrative fiction as far as she could. The result was a big success in two senses. It produced a radical contribution to the modernist movement in a novel which sits coherently alongside other literary works such as T.S.Eliot’s The Waste Land (1923) and James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). And it gave her the confidence to realise that she had succeeded in producing something new and original which expressed her own sense of an authentic ‘inner voice’.

I figure that the approach will be entirely different this time; no scaffolding; scarcely a brick to be seen; all crepuscular, but the heart, passion, humour, everything, as bright as fire in the mist. Then I’ll find room for so much—a gaiety—an inconsequence— a light spirited stepping at my sweet will. Whether I’m sufficiently mistress of things—that’s the doubt; but conceive Mark on the Wall, Kew Gardens, and Unwritten Novel taking hands and dancing in unity.

Virginia Woolf

Jacob’s Room – critical commentary

Experimentation

This is the first of Virginia Woolf’s novels in which she made a radical and decisive shift away from conventional prose narrative. What the outcome would be, she wasn’t sure, but she realised that she was onto something quite new.

The most obvious innovation is that the narrative is discontinuous and the novel does not a have a plot in the conventional sense. The story starts on one topic or character, then switches to something or somebody else with no warning or explanation. Readers are dropped into a situation, and are left to work out the who, when, and where of the subject with very little assistance. Few clues are given, and after a few lines of developing a topic, Woolf changes it again to something else.

Connections between these fragments of narrative ultimately become perceptible, but only after a lot of patience and work on the reader’s part.

Point of view

There is also a repeatedly shifting point of view. A character such as Betty Flanders in the opening of the novel might be used as a focalising mechanism. We see events from her perspective or are presented with her inner thoughts – such as her ambiguous feelings about her correspondent and suitor Captain Barfoot. But then the narrative switches to present her not as the subject, but as the object of someone else’s point of view.

‘Scarborough,’ Mrs Flanders wrote on the envelope, and dashed a bold line beneath; it was her native town; the hub of the universe. But a stamp? She ferreted in her bag; then held it up mouth downwards; then fumbled in her lap, all so vigorously that Charles Steele in the Panama hat suspended his paint brush

Charles Steele has no connection with Betty, other than being on the beach at the same time, but for the next page or so we see Betty from his point of view as a figure in his painting, he speaks to Betty’s son, and we are given a glimpse into his thoughts about painting, and then he disappears and will never appear in the novel again.

Literary modernism

What is Virginia Woolf trying to achieve in this form of story telling? She had criticised contemporary fiction (particularly that of Arnold Bennett) in her 1919 essay Modern Novels because she thought most novelists failed to give a proper account of what life was like. They piled up fact after fact about their characters, but were unable to create any sense of the ‘pulse of life’ or the poetry of what it was like to be alive.

So her literary impressionism (or cubism?) was an attempt to give an account of the simultaneity of people’s existences as they lived alongside each other. Some connections were meaningful, others were no more than coincidence.

Interestingly enough, she uses the city as both a subject and symbol of modernism in exactly the same way as her contemporaries Marcel Proust In Search of Lost Time (1913), Andrei Bely St Petersburg (1913), James Joyce Ulysses (1922), and Alfred Döblin Berlin Alexanderplatz, (1929).

The throngs of people flowing incessantly across Waterloo Bridge are offered as a compressed image of anonymous urban humanity in its many guises.

All the time the stream of people never ceases passing from the Surrey side to the Strand; from the Strand to the Surrey side. It seems as if the poor had gone raiding the town, and now traipsed back to their own quarters, like beetles scurrying to their holes, for that old woman fairly hobbles towards Waterloo, grasping a shiny bag, as if she had been out into the light and now made off with some scraped chicken bones to her hovel underground. On the other hand, though the wind is rough and blowing in their faces, those girls there, striding hand in hand, shouting out a song, seem to feel neither cold nor shame. They are hatless. They triumph.

Reflections and communication

But there are further elements to her technical experimentation. She added to her narrative strategies the device of embedding lyrically poetic reflections on life and the natural world – passages which are a combination of prose poem and philosophic meditation. Mrs Flanders and Jacob send letters to each other in an attempt at communication which often fails for Betty, because Jacob does not reveal his inner life (something many parents will recognise) but Woolf interrupts the story to reflect on written correspondence:

Let us consider letters—how they come at breakfast, and at night, with their yellow stamps and their green stamps, immortalized by the postmark—for to see one’s own envelope on another’s table is to realize how soon deeds sever and become alien.

Almost all the conversations between characters are fragmentary – snatches of speech which do little more than identify a subject and demonstrate that some attempt at communication is taking place, despite the fact that in many cases waht is revealed is a lack of understanding.

The flux of time

There are also some well-orchestrated temporal shifts which contribute to the destabilization of the narrative flow but reinforce the sense of ‘architecture’ Woolf said she wished to bring to the novel. Jacob and his brother Archer are tutored as a boys by the young clergyman Mr Floyd, who makes an unsuccessful offer of marriage to Mrs Flanders.

But the letter Mr Floyd found on the table when he got up early next morning did not begin ‘I am much surprised’, and it was such a motherly, respectful, inconsequent, regretful letter that he kept it for many years; long after his marriage with Miss Wimbush of Andover; long after he had left the village.

The flash forward (technical term ‘prolepsis’) tells us that he later marries Miss Wimbush and leaves to live somewhere else. In fact within a short paragraph a potted life history gives the full trajectory of his future life as a clergyman, a college principal, and a writer, right up to his retirement, at which point he sees the mature Jacob in Piccadilly but does not speak to him.

Two hundred pages later, when the novel has followed Jacob’s development as a young man to (almost) full maturity the same incident is repeated, this time from Jacob’s point of view.

This fluid telescoping of time is also conducted at a macro level where the same scene might be described in the narrative present, then shift to consider how it might have seemed in the eighteenth or the nineteenth century.

Fragmentation

One problem in this technique of extreme fragmentation is that characters who seem important at one point in the narrative do not appear again and are not relevant to any major theme other than the fact that people’s lives sometimes overlap. There is no resolution to the Betty Flanders and Captain Barfoot connection for instance. He is an important suitor to Betty in the opening pages of the novel (even though he is already married – but to an invalid). But we never learn what happens to this connection. All it tells us is that Betty Flanders is obviously an attractive women to men of varied ages.

Woolf was to use all these techniques more successfully in her later works such as Mrs Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, Orlando, and The Waves, where they seem to have been anchored more coherently to the characters and the underlying themes. But it is here that she was trying them out for the first time.

Jacob’s Room – study resources

![]() Jacob’s Room – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

Jacob’s Room – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Jacob’s Room – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

Jacob’s Room – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() Jacob’s Room – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

Jacob’s Room – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Jacob’s Room – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

Jacob’s Room – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() Jacob’s Room – the holograph draft – Amazon UK

Jacob’s Room – the holograph draft – Amazon UK

![]() Jacob’s Room – Kindle annotated edition – Amazon UK

Jacob’s Room – Kindle annotated edition – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf – biographical notes

Virginia Woolf – biographical notes

![]() Selected Essays – by Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

Selected Essays – by Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Virginia Woolf at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Jacob’s Room – plot summary

It is extremely difficult to summarise the plot, for reasons that are made clear in the critical commentary above. Virginia Woolf was experimenting with a new form of narrative in which the ‘story’ shifts from one topic to another – even within the same paragraph or sentence. She tried to create a form of story telling in which several things are being discussed at the same time, creating an impression of simultaneity. This was not unlike the form of experimentation going on in the visual arts – particularly cubism, which strove to depict images of a single object from multiple points of view in the same two dimensional picture. For further comments on this feature of Virginia Woolf’s literary techniques, see my review article Virginia Woolf and Cubism.

It is extremely difficult to summarise the plot, for reasons that are made clear in the critical commentary above. Virginia Woolf was experimenting with a new form of narrative in which the ‘story’ shifts from one topic to another – even within the same paragraph or sentence. She tried to create a form of story telling in which several things are being discussed at the same time, creating an impression of simultaneity. This was not unlike the form of experimentation going on in the visual arts – particularly cubism, which strove to depict images of a single object from multiple points of view in the same two dimensional picture. For further comments on this feature of Virginia Woolf’s literary techniques, see my review article Virginia Woolf and Cubism.

Part I. Elizabeth (Betty) Flanders, recently widowed, is on holiday on a beach in Cornwall with her sons Archer and Jacob.

Part II. At home in Scarborough, Betty receives a marriage proposal from Reverend Floyd. Her friend Mrs Jarvis has romantic yearnings. Captain Barfoot (a married suitor) calls on Mrs Flanders.

Part III. Jacob goes to Trinity College Cambridge. He integrates with undergraduate life, though he’s a little awkward. Sunday lunch at a don’s house, and late night discussions with fellow students.

Part IV. Summer vacation. Jacob and his friend Timothy Durrant sail round the coast of Cornwall. They are present at a dinner party given by Timmy’s wealthy mother. He meets Clara Durrant.

Part V. Jacob in London after graduating, amidst scenes of metropolitan complexity. He visits the opera (Tristran and Isolde) with the Durrants. He writes a critical essay which is not published.

Part VI. Jacob socialises in London amidst artistic types. At November 5th celebrations he meets Florinda at a fancy dress party and takes her back to his lodgings.

Part VII. Jacob is present at a musical evening, and he meets Clara Durrant again.

Part VIII. Betty Flanders writes to Jacob, hoping for meaningful and substantial news. But Jacob does not reveal the essence of his life to her, which includes the fact that he realises that Florinda is a tart.

Part IX. Jacob goes hunting in Essex and socialises in upper middle class circles, and at the same times visits prostitutes. He also spends time in the British Museum Library, researching the poetry of Christopher Marlowe.

Part X. Ex-Slade School of Art student Fanny Elmer models for an artist and meets Jacob in his studio. She is deeply impressed with Jacob, and buys a copy of Tom Jones on his recommendation.

Part XI. Jacob inherits £100 from a relative and goes to France with his artistic friends. Betty Flanders visits the Scarborough moors with her friend Mrs Jarvis.

Part XII. Jacob travels on alone through Italy and Greece, writing to his friend Bonamy. He meets fellow English tourists Mr and Mrs Wentworth Williams and falls in love with the wife, Sandra.

Part XIII. The principal characters are seen in London during the summer. Bonamy’s gay infatuation with Jacob is made clear.

Part XIV. Bonamy and Betty Flanders clear out Jacob’s room following his death during the war.

Jacob’s Room – principal characters

| Elizabeth (Betty) Flanders | widow from Scarborough (45) |

| Archer Flanders | her eldest son |

| Jacob Alan Flanders | her middle son |

| John Flanders | her youngest son |

| Charles Steele | a painter on the beach in Cornwall |

| Mrs Pearce | Cornish lodging house owner |

| Rebecca | family servant |

| Captain Barfoot | Betty’s correspondent and suitor (50) |

| Mrs Barfoot | an invalid, his wife |

| Mr Dickens | Mrs Barfoot’s wheelchair attendant |

| Seabrook Flanders | Betty’s dead husband |

| Morty | Betty’s brother who goes to the East |

| Andrew Floyd | young clergyman and suitor to Betty |

| Mrs Jarvis | Betty’s friend, a romantic and needy clergyman’s wife |

| Timothy (Timmy) Durrant | Jacob’s friend at Cambridge who becomes a clerk in Whitehall |

| George Plummer | Cambridge don and professor of physics |

| Mrs Plummer | his wife |

| Mrs Pascoe | a Cornish woman |

| Mrs Durrant | Timmy’s rich mother |

| Clara Durrant | Timmy’s sister |

| Richard Bonamy | Jacob’s gay friend at Cambridge |

| Florinda | a loose girl in bohemian London |

| Lauretta | a prostitute |

| Fanny Elmer | an ex-Slade student who falls for Jacob |

| Edward Cruttendon | a friend of Jacob’s |

| Mallinson | a painter friend of Jacob’s |

| Jinny Carslake | a friend on the trip to Paris |

| Sandra Wentworth Williams | flirtatious woman in hotel in Greece |

| Evan Williams | her jealous husband |

Further reading

![]() Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

![]() Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

![]() Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

![]() John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

![]() Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

![]() Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

![]() Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Vit=rginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Vit=rginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

![]() Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

![]() Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

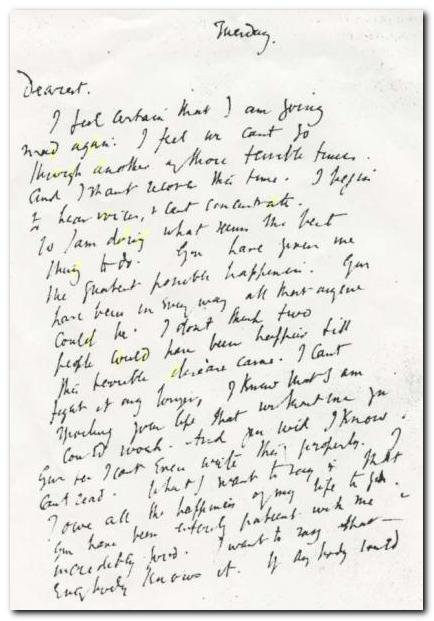

“I feel certain that I am going mad again.”

Other works by Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a triptych of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a triptych of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2012

Virginia Woolf – web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

Book reviews, Bloomsbury related issues, links, study resources, news of conferences, exhibitions, and events, regularly updated.

![]() Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of her work, fiction and non-fiction publications, photograph albumns, list of biographies, and external web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Selected eTexts of the novels The Voyage Out, Night and Day, Jacob’s Room, and the collection of stories Monday or Tuesday in a variety of digital formats.

![]() Woolf Online

Woolf Online

An electronic edition and commentary on To the Lighthouse with notes on its composition, revisions, and printing – plus relevant extracts from the diaries, essays, and letters.

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search texts of all the major novels and essays, word by word – locate quotations, references, and individual terms

![]() Virginia Woolf – a timeline in phtographs

Virginia Woolf – a timeline in phtographs

A collection of well and lesser-known photographs documenting Woolf’s life from early childhood, through youth, marriage, and fame – plus some first edition book jackets – to a soundtrack by Philip Glass. They capture her elegant appearance, the big hats, and her obsessive smoking. No captions or dates, but well worth watching.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury – including Gordon Square, Gower Street, Bedford Square, Tavistock Square, plus links to women’s history web sites.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Bulletins of events, annual lectures, society publications, and extensive links to Woolf and Bloomsbury related web sites

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

Charming sound recording of radio talk given by Virginia Woolf in 1937 – a podcast accompanied by a slideshow of photographs.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephen compiled a photograph album and wrote an epistolary memoir, known as the “Mausoleum Book,” to mourn the death of his wife, Julia, in 1895 – an archive at Smith College – Massachusetts

![]() Virginia Woolf first editions

Virginia Woolf first editions

Hogarth Press book jacket covers of the first editions of Woolf’s novels, essays, and stories – largely designed by her sister, Vanessa Bell.

![]() Virginia Woolf – on video

Virginia Woolf – on video

Biographical studies and documentary videos with comments on Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group and the social background of their times.

![]() Virginia Woolf Miscellany

Virginia Woolf Miscellany

An archive of academic journal essays 2003—2014, featuring news items, book reviews, and full length studies.

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group