tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

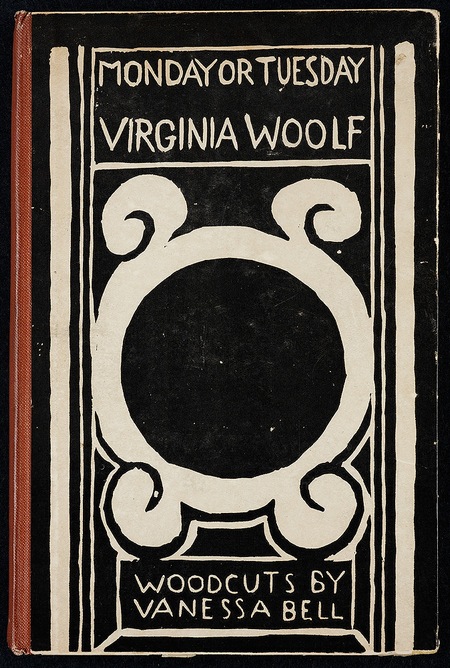

A Haunted House first appeared in Monday or Tuesday (1921) – a collection of experimental short prose pieces Virginia Woolf had written between 1917 and 1921. It was published by the Hogarth Press and also included A Society, Monday or Tuesday, An Unwritten Novel, The String Quartet, Blue and Green, and Solid Objects.

Virginia Woolf

A Haunted House – critical commentary

Pronouns

First time readers of this story are likely to be bewildered by Woolf’s very indirect form of narrative, the lack of formal identification of anybody in the story, and her switching between one pronoun and another.

In the opening sentence – ‘Whatever hour you awoke’ – she is using you in the sense of one, not speaking of any person in particular. In the very next sentence – ‘From room to room they went’ – they refers to the ‘ghostly couple’ who are re-visiting the house in search of something.

They are referred to as she and he in what follows, but in their imagined conversation – ‘Quietly’ they said, ‘or we shall wake them’ – the them refers to the couple who currently occupy the house, one of whom is the narrator of the story.

And the point of view switches back to the narrator, who confirms ‘But it wasn’t that you woke us’, and goes on to observe ‘They’re looking for it’. At this point it is not at all clear what it refers to. It appears be something like the spirit of the house: ‘Safe, safe, safe,’ the pulse of the house beat gladly, ‘The treasure yours.’

The ghostly couple then revisit their old bedroom, where the current occupants are asleep. They reflect on their own previous happiness there, which parallels that of the current occupiers, and the narrator, who has been imagining the visiting ghosts, awakens to wonder if the hidden treasure they were seeking was a sense of joy at living there.

A Haunted House -study resources

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

![]() Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

![]() A Haunted House – Hogarth reprint edition – Amazon UK

A Haunted House – Hogarth reprint edition – Amazon UK

![]() A Haunted House – Hogarth reprint edition – Amazon US

A Haunted House – Hogarth reprint edition – Amazon US

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

A Haunted House – story synopsis

An un-named narrator and one of the current occupants of an old house recounts the impression of a visit to it by previous occupants in the form of ghosts.

The ghostly couple are in search of something, and move through the rooms, whilst the narrator is reading in the garden.

The house and its garden are evoked with rural images, shafts of light and shade, and the passage of time and seasons.

The ghostly couple re-visit their old bedroom at night where the current occupants are asleep. They find what they are looking for – in the form of memories of their previous existence, doing the same things as the current occupants, living in harmony with the house.

A Haunted House – principal characters

| I | the narrator |

| you (singular) | as in ‘one’ |

| they | the previous occupants of the house |

| she | previous occupant |

| he | previous occupant |

| it | the ‘ghostly treasure’ |

| them | the current occupants of the house |

| you (plural) | the previous occupants |

| us | the current occupants |

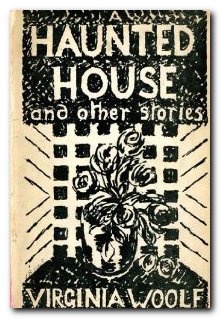

A Haunted House – first edition

Cover design by Vanessa Bell

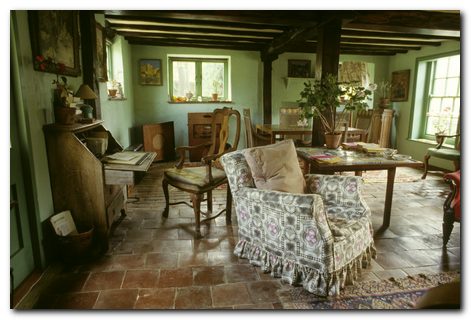

Monk’s House – Rodmell

Virginia Woolf’s old house in Sussex

Further reading

![]() Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

![]() Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

![]() Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

![]() John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

![]() Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

![]() Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

![]() Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

![]() Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

![]() Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Other works by Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction contains all the classic short stories such as The Mark on the Wall, A Haunted House, and The String Quartet – but also the shorter fragments and experimental pieces such as Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street. These ‘sketches’ (as she called them) were used to practice the techniques she used in her longer fictions. Nearly fifty pieces written over the course of Woolf’s writing career are arranged chronologically to offer insights into her development as a writer. This is one for connoisseurs – well presented and edited in a scholarly manner.

The Complete Shorter Fiction contains all the classic short stories such as The Mark on the Wall, A Haunted House, and The String Quartet – but also the shorter fragments and experimental pieces such as Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street. These ‘sketches’ (as she called them) were used to practice the techniques she used in her longer fictions. Nearly fifty pieces written over the course of Woolf’s writing career are arranged chronologically to offer insights into her development as a writer. This is one for connoisseurs – well presented and edited in a scholarly manner.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2013

Virginia Woolf – web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

Book reviews, Bloomsbury related issues, links, study resources, news of conferences, exhibitions, and events, regularly updated.

![]() Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of her work, fiction and non-fiction publications, photograph albumns, list of biographies, and external web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Selected eTexts of her novels and stories in a variety of digital formats.

![]() Woolf Online

Woolf Online

An electronic edition and commentary on To the Lighthouse with notes on its composition, revisions, and printing – plus relevant extracts from the diaries, essays, and letters.

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search texts of all the major novels and essays, word by word – locate quotations, references, and individual terms

![]() Orlando – Sally Potter’s film archive

Orlando – Sally Potter’s film archive

The text and film script, production notes, casting, locations, set designs, publicity photos, video clips, costume designs, and interviews.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury – including Gordon Square, Gower Street, Bedford Square, Tavistock Square, plus links to women’s history web sites.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Bulletins of events, annual lectures, society publications, and extensive links to Woolf and Bloomsbury related web sites

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

Charming sound recording of radio talk given by Virginia Woolf in 1937 – a podcast accompanied by a slideshow of photographs.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephen compiled a photograph album and wrote an epistolary memoir, known as the “Mausoleum Book,” to mourn the death of his wife, Julia, in 1895 – an archive at Smith College – Massachusetts

![]() Virginia Woolf first editions

Virginia Woolf first editions

Hogarth Press book jacket covers of the first editions of Woolf’s novels, essays, and stories – largely designed by her sister, Vanessa Bell.

![]() Virginia Woolf – on video

Virginia Woolf – on video

Biographical studies and documentary videos with comments on Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group and the social background of their times.

![]() Virginia Woolf Miscellany

Virginia Woolf Miscellany

An archive of academic journal essays 2003—2014, featuring news items, book reviews, and full length studies.

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – short stories

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

Virginia Woolf – life and works

Alejo Carpentier was a Cuban writer who straddled the connection between European literature and the native culture of Latin-America. He was for a long time the Cuban cultural ambassador in Paris. Carpentier was trying to place Latin-American culture into a historical context. This was done via a conscious depiction of the colonial past – as in The Kingdom of This World, and Explosion in a Cathedral (title in Spanish El Siglo de las Luces – or The Age of Enlightenment).

Alejo Carpentier was a Cuban writer who straddled the connection between European literature and the native culture of Latin-America. He was for a long time the Cuban cultural ambassador in Paris. Carpentier was trying to place Latin-American culture into a historical context. This was done via a conscious depiction of the colonial past – as in The Kingdom of This World, and Explosion in a Cathedral (title in Spanish El Siglo de las Luces – or The Age of Enlightenment). The Kingdom of This World

The Kingdom of This World The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps Explosion in a Cathedral

Explosion in a Cathedral The Chase

The Chase

In fact the depictions of his subjects become more and more heroic, almost in inverse proportion to the degree of social and political misery in the Soviet Union under Stalin. There is very little evidence (anywhere) of his work beyond 1940, even though he lived until 1956 – although there is one astonishing image in this collection dated 1943-44 which you would swear was a Jackson Pollock painting. But it seems quite obvious that the creative highpoint of his career is the 1920s, when he was free to experiment and theorise with his fellow pioneers, and even (dare one say it) when the state encouraged and supported such experimentation.

In fact the depictions of his subjects become more and more heroic, almost in inverse proportion to the degree of social and political misery in the Soviet Union under Stalin. There is very little evidence (anywhere) of his work beyond 1940, even though he lived until 1956 – although there is one astonishing image in this collection dated 1943-44 which you would swear was a Jackson Pollock painting. But it seems quite obvious that the creative highpoint of his career is the 1920s, when he was free to experiment and theorise with his fellow pioneers, and even (dare one say it) when the state encouraged and supported such experimentation.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens

Strangely enough, there was no Art Nouveau school of painting, mainly because it constituted an approach to design. It was in the realm of posters, woodcuts, illustrated books, and typography that it made its greatest impact, and there are excellent examples of posters by Lautrec, Mucha, and Bonnard. These were works which gave birth to the figure that came to symbolise fin de siecle Paris and la Belle Epoque – a young woman with serpentine hair, clad fashionably in jewelled or feathered headgear and wearing immense sweeping skirts, all of which flowed abundantly to fill the frame of the picture. It’s amazing to realise that these romantically stylised images were being used to advertise such mundane objects as bicycles, wine, household soap, and cigarette papers.

Strangely enough, there was no Art Nouveau school of painting, mainly because it constituted an approach to design. It was in the realm of posters, woodcuts, illustrated books, and typography that it made its greatest impact, and there are excellent examples of posters by Lautrec, Mucha, and Bonnard. These were works which gave birth to the figure that came to symbolise fin de siecle Paris and la Belle Epoque – a young woman with serpentine hair, clad fashionably in jewelled or feathered headgear and wearing immense sweeping skirts, all of which flowed abundantly to fill the frame of the picture. It’s amazing to realise that these romantically stylised images were being used to advertise such mundane objects as bicycles, wine, household soap, and cigarette papers.