tutorial, study resources, plot summary, web links

The Invisible Man was first published as an abridged serial version in Pearson’s Weekly in 1897. It then appeared in single volume book format later the same year in England and America. It is worth noting that the ‘Epilogue’ that follows the end of the main story was added after the first edition. This does not significantly alter the ‘facts’ of the main narrative, but it does introduce a shift in tone after the dramatic finale to the tale.

The Invisible Man – critical commentary

The structure

The story is split into three parts, which are presented out of their chronological sequence. If the actual order of events as they happened is represented by 1- 2 – 3, they are revealed to the reader in the order 2 – 1 – 3. In other words the novel begins part way through the story.

The Invisible Man is on the run when he arrives in the village of Iping at the start of the novel, causing havoc amongst the Sussex locals. This is the start of Part 2 in the events of the narrative. After a lot of high jinx amongst the villagers, he locates his friend Dr Kemp, to whom he then reveals the origins and the scientific basis of his experiment, and the reasons he has had to escape from London. His account to Kemp is Part 1 of events, or the ‘back story’.

When Kemp alerts the police to the possible danger posed by the Invisible Man, this leads to the attack on Kemp’s house then to the pursuit of the Invisible Man. These events constitute Part 3 of the novel, which culminates in his being killed by a man with a shovel.

As a structure it has a lot of potential – because as readers we are as puzzled as the hapless residents of Iping by the strange events at the start of the novel. In Part 1 we do not know why the man is invisible or how he has got into such a state. Then in Part 2 we are given a quasi-scientific ‘explanation’ of how this experiment has been brought about. Finally, in Part 3 we are invited to witness some of its social and personal consequences.

But the problem is that there are huge differences of tone and content in the three different parts – and very little in the way of a common thread holding them all together.

The first part of the novel reads like a third rate farce, or the story line in a children’s comic. There are stock yokel figures baffled by events they do not understand – which include disappearing clothes, moving furniture, interfering vicar and local doctor, doors mysteriously opening and closing, and a melee at the Whit Monday festival, with people actually crying out “Stop thief!”. There is nothing remotely serious in these events.

Yet when the Invisible Man explains the origins and development of his experimental investigations to Kemp, we are expected to take the narrative seriously. And maybe we do – up to a point. But there are major shifts in tone and substance which disrupt the coherence of the text.

Suddenly in the second part of the novel the Invisible Man runs out of money and robs his own father, who in turn commits suicide, because his money belonged to somebody else. Then the Invisible Man sets fire to the house where he lodges (which just happens to be owned by a Jew). These are events of a different kind that belong to a different literary genre from the events in the first part of the novel.

In the final part of the story we are expected to believe that the Invisible Man becomes a homicidal maniac and suddenly develops a desire to establish a ‘Reign of Terror’. There is no credible psychological explanation offered for this sudden megalomania. None of this presaged by what we know of him from the earlier parts of the story, and the switch from farce to what purports to be a sort of existential terror is just not credible.

Is it a novel?

H.G. Wells classified the books of the 1890s that catapulted him to fame as ‘scientific romances’. The term ‘romance’ had originally been a literary genre for works that were set in non-real or imaginary worlds. Wells was following the trend set in France by Jules Verne with works such as Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863), Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1870), and Around the World in 80 Days (1873). All of these (including Wells’ own stories) are what we now call ‘science fiction’.

But The Invisible Man is set in the very real worlds of London and the Sussex downs and seacoast, so it does not fall into the ‘romance’ category. The events of the narrative centre almost exclusively on one character – the Invisible Man. Only the character of his friend Dr Kemp is in any way psychologically developed, and the narrative makes no attempt to develop secondary themes or the social texture of a realistic fiction.

It is less than 50,000 words long – yet it does not have any of the thematic density and intellectual coherence of a novella – so perhaps the safest classification would be to call it a ‘short novel’.

One good idea

The Invisible Man is one of H.G. Wells’ earliest works, and it can hardly be called a literary success. The writing is clumsy and full of cliches; his characterisation is amateurish; he makes lots of mistakes in the chronology of events (even describing scenes twice); and the novel seems to change its purpose as the story progresses. Yet just as in his novel of the previous year (The Island of Doctor Moreau) he created a work with lasting appeal because it based on one good idea.

We know that even the cleverest research scientist cannot really make himself invisible. (Just as we know that Doctor Moreau cannot really make half-human creatures out of animals and teach them to speak.) But we are prepared to suspend our disbelief in exchange for literary entertainment and maybe some thought-provoking ideas.

The idea of somebody making himself invisible is one of those good single ideas that have struck home, endured, and spread – especially in the realms of popular media. There have been several screen adaptations of the novel, and lots of spin offs. This is the 1933 version directed by James Whale, with screenplay by R.C. Sherriff. Starring – Claude Rains (Dr Jack Griffin, The Invisible Man), Gloria Stuart (Flora Cranley), William Harrigan (Dr Arthur Kemp), and Henry Travers (Dr Cranley). Filmed in Universal Studios, California.

The Invisible Man – study resources

![]() The Invisible Man – Penguin Classics- Amazon UK

The Invisible Man – Penguin Classics- Amazon UK

![]() The Invisible Man – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Invisible Man – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() H.G. Wells Classic Collection – five novels – Amazon UK

H.G. Wells Classic Collection – five novels – Amazon UK

![]() H.G. Wells Biography – Amazon UK

H.G. Wells Biography – Amazon UK

![]() The Invisible Man – DVD film adaptation – Amazon UK

The Invisible Man – DVD film adaptation – Amazon UK

The Invisible Man – chapter summaries

1 A man arrives at the Sussex village of Iping during winter. Mrs Hall the landlady of the Coach and Horses is puzzled by his bandaged face and secretive manner. She assumes he has been in an accident.

2 The man claims to be making ‘experimental investigations’, and impatiently demands isolation and quietness.

3 Next day the man’s luggage arrives, consisting largely of bottles and books. When he is bitten by a dog, no flesh shows through the rent in his trousers.

4 The villagers are baffled, curious, and hostile. The local doctor challenges the man and cannot understand his ’empty sleeve’ which seems to contain something solid.

5 There is a burglary at the vicarage, but nobody can be seen in the house when the vicar goes to inspect.

6 Mr and Mrs Hall are snooping in the man’s room when he surprises them by entering – first invisibly, then reappearing fully dressed.

7 When challenged by Mrs Hall over an unpaid bill, the man takes the bandages off his head to prove that he is invisible. This creates a skirmish in the pub, from which he escapes.

8 Out on the Sussex downs, a local naturalist hears somebody sneezing nearby, but can see nothing.

9 The Invisible Man comes across a tramp, Thomas Marvel, whose help he seeks to acquire clothes and shelter.

10 The tramp goes into Iping during the Whitsuntide festival to obtain clothes.

11 At the Coach and Horses, the doctor and vicar are looking through the Invisible Man’s diaries when he enters and threatens them.

12 The Invisible Man and the Tramp steal clothes and cause mayhem amongst their pursuers.

13 The tramp Marvel complains about the way he is being treated, but the Invisible Man dominates and threatens him.

14 At Port Stowe Marvel is in conversation with a sailor who tells him about a newspaper report of events at Iping.

15 Dr Kemp in Burdock sees Marvel running across the fields, raising an alarm about the possible appearance of the Invisible Man.

16 Marvel seeks refuge in the Jolly Cricketers. When the Invisible Man arrives, the pub clientele attack him.

17 An injured Invisible Man breaks into the house of Dr Kemp, who gives him food and drink. They are former university contemporaries.

18 Whilst the Invisible Man sleeps, Kemp reads newspaper reports of the incidents at Iping and wonders what he should do. He sends a note to the police.

19 Next day the Invisible Man explains his invisibility to Kemp. It is based on the reflective power of human tissue. He has worked in secret for more than three years on the experiment, but having run short of funds he has robbed his own father. The money belonged to somebody else, and his father has committed suicide.

20 The Invisible Man recounts the early stages of experimenting to Kemp, including making a cat (almost) invisible. Threatened by his landlord in London with eviction, he makes himself the subject of experimentation. He sets fire to the house, and leaves invisibly.

21 The man mixes amongst crowds in Oxford Street but realises he is leaving a trail of wet footprints.

22 The man goes to hide in a department store, where he steals food and clothing. But he is discovered next morning and gives up the idea of staying there.

23 The man goes to hide in the house of a theatrical costumier in Drury Lane He knocks out the owner and robs the shop.

24 The man explains to Kemp his vague plans to escape to North Africa, but first he wants Kemp to be an accomplice in establishing a Reign of Terror. When the police arrive he escapes again.

25 Kemp and the police make plans for recapturing the Invisible Man.

26 A widespread manhunt is organised, and the murder of an estate steward with an iron bar is attributed to the Invisible Man.

27 Next day Kemp receives a death threat. He sends his housekeeper with a note to the police, but she is attacked b the Invisible Man. The police chief is also attacked and killed. The invisible Man breaks into Kemp’s house but is attacked by two policemen.

28 Kemp escapes from the house and runs downhill into town, pursued by the Invisible Man. Eventually, a crowd forms in pursuit, and the Invisible Man is caught and killed.

Epilogue The tramp Marvel has become a pub landlord and has the Invisible Man’s three notebooks in his possession, the contents of which he does not understand.

The Invisible Man – principal characters

| The Invisible Man | Griffin, a former scientist |

| Dr Kemp | his contemporary at university |

| Mrs Hall | landlady of the Coach and Horses |

| Adye | local police chief |

| Thomas Marvel | a tramp, later a publican |

More science fiction by H.G. Wells

![]() The Time Machine (1895) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Time Machine (1895) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Wheels of Chance (1896) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Wheels of Chance (1896) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The War of the Worlds (1898) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The War of the Worlds (1898) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The First Men in the Moon (1901) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The First Men in the Moon (1901) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Shape of Things to Come (1933) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Shape of Things to Come (1933) – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

More on H.G. Wells

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece. Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed.

Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed.

The Kingdom of This World

The Kingdom of This World The Chase

The Chase The novel is an ironic reversal of the rags to riches story that is normally attached to immigration from the Old World to the New. Karl Rossman manages to go from riches to rags. He starts off with a wealthy and powerful uncle who showers him with luxury, but by the end of the narrative he has nothing, he is searching for work, and he is mixing with criminals and a prostitute. It is worth noting that Karl is not exactly an innocent abroad. He has been expelled from his family home following a sexual dalliance with an older servant woman that resulted in her bearing a child. So although he is only seventeen (or even fifteen) years old, Karl is in fact himself a father.

The novel is an ironic reversal of the rags to riches story that is normally attached to immigration from the Old World to the New. Karl Rossman manages to go from riches to rags. He starts off with a wealthy and powerful uncle who showers him with luxury, but by the end of the narrative he has nothing, he is searching for work, and he is mixing with criminals and a prostitute. It is worth noting that Karl is not exactly an innocent abroad. He has been expelled from his family home following a sexual dalliance with an older servant woman that resulted in her bearing a child. So although he is only seventeen (or even fifteen) years old, Karl is in fact himself a father.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis The Trial

The Trial

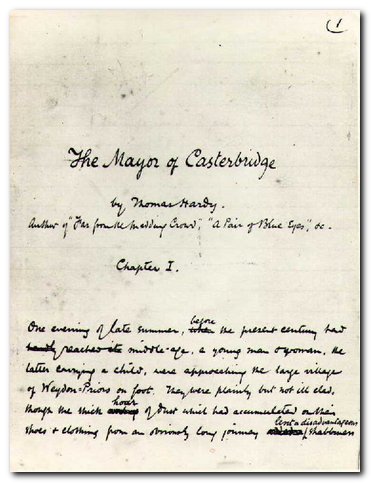

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles Jude the Obscure

Jude the Obscure Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

Ethan Frome

Ethan Frome The Age of Innocence

The Age of Innocence The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth The Reef

The Reef