controversial Anglo-American modernist sculptor

Jacob Epstein (1880-1959) was a sculptor who became a controversial pioneer in the world of modernist British art. He was born in New York’s Lower East Side to Jewish immigrant parents who had escaped anti-Semitic pogroms in Poland. When the family moved to a more respectable neighbourhood, he chose to remain amongst the ‘Russian, Poles, Italians, Greeks, and Chinese’ who clustered in what was then a very unfashionable part of the city.

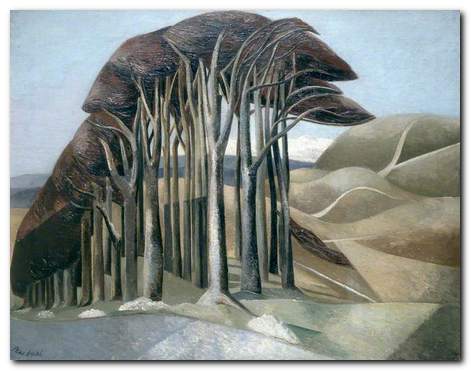

Rock Drill

In 1902 he travelled to France, enrolling at the Ecole de Beaux Arts and visiting Rodin’s studio. He was a fan of his fellow countryman Walt Whitman, and there is a distinct element of homo-eroticism in his early works that parallels the celebration of the human body (largely Male) that features in Whitman’s poems. This is an element of his vision that became important in later works and his battles with censorship and even the mutilation of his statues and carvings.

In 1905 he transferred to London and quickly made contact with people such as George Bernard Shaw and Augustus John. Even more surprisingly he secured a large public commission at the age of only twenty-seven. This was for a series of decorative statues for the new headquarters of the British Medical Association in the Strand.

The nude figures he produced depicting maternity and Hygieia (goddess of health and cleanliness) became the target of outraged prudish hostility, and a press campaign was mounted by the Evening Standard. The project was completed, but it was twenty years before he received another architectural commission.

He was supported and befriended by Eric Gill, who had similar ambitions to bring primitive elemental forms into public art. They planned to build a private temple in Sussex where they could express their enthusiasm for nudity and sexuality without hindrance. The project was never completed, but the celebration of human physicality pervaded almost everything they went on to produce.

Epstein’s next major work was the now-famous tomb of Oscar Wilde in Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris. This was admired by the young fellow-immigrant artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, but the French authorities protested against the winged figure’s nakedness and ordered its genitals to be obliterated. They were later hacked off by protesters more than once.

Meanwhile his domestic life was no less controversial. He was married to Margaret Dunlop but at the same time he had a number of lovers who his wife not only tolerated but allowed to live in the family home, along with the children who were conceived by them as a result.

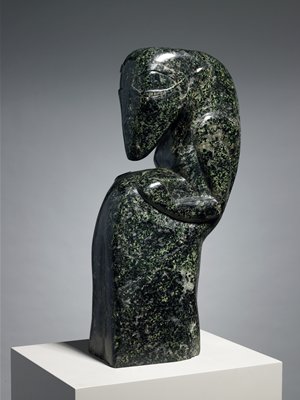

Epstein isolated himself in a Sussex coastal village and produced a number of excellent abstracted figures of pregnant females and copulating doves, clearly influenced by the work of Constantin Brancusi who he had met in Paris. It has to be said that the works of Epstein, Brancusi, and Gaudier-Brzeska became almost indistinguishable around this period.

Just before the outbreak of war, in 1913 Epstein produced the first drawings for what was to become his most important work – Rock Drill. In its first version the dramatically modelled figure of a quarry worker was mounted astride a tripod, handling a real drilling machine.

Nothing could have better symbolised the Vorticist movement which championed his work in the second (and final) edition of its magazine BLAST. But Epstein refused to join the group founded by his supporter Wyndham Lewis. In fact Epstein was so appalled by the mechanised slaughter of young soldiers in the conflict of 1914-1918 that he removed the drill and tripod from the original sculpture.

This turned out to produce a much more aesthetically pleasing result – the futuristic head and torso which seemed to symbolise the machine age. Yet following this success his activity more or less split into two parts. The first was producing traditional bronze portrait busts for celebrities in a style that could have come from any time in the previous two-hundred years. The second was his far more interesting series of monumental carvings and sculptures that expressed something of the modern age. The first part provided him with an income; the second with continued notoriety.

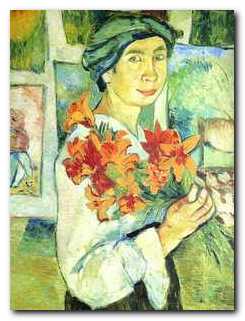

Femaile Figure

It is amazing to recall the virulent hostility (and anti-Semitism) that his work aroused. Even the Royal Academy participated in the mutilation of his public commissions. Following the exhibition of his controversial Adam (1938) the statue was sold off for next to nothing and later displayed in a Blackpool funfair. Visitors were charged a shilling entry to view its enlarged genitals as a form of pornographic amusement. The same fate befell his next major work, Jacob and the Angel (1941) – though this has since been rescued and is now in the relative safety of the Tate Gallery.

He participated in the Festival of Britain 1951) but by this time he was being outflanked by younger contemporaries such as Henry Moore, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Lynn Chadwick. He completed further commissions for religious figures, notably on the re-built Coventry Cathedral, but his final secular work was the magnificent war memorial that stands in front of TUC headquarters at Congress House in London.

He was knighted in 1954, but his later years were marked by personal loss. His son died of a heart attack in 1954, and his daughter committed suicide later the same year. Epstein himself died in 1959 at Hyde Park Gate in Kensington – next door but one to the birthplace of Virginia Woolf.

© Roy Johnson 2018

Jacob Epstein biography – But the book at Amazon UK

Jacob Epstein biography – Buy the book at Amazon US

More on art

More on media

More on design

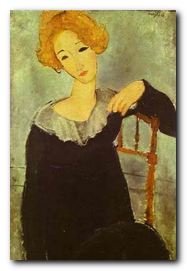

Mark Gertler (1896—1939) was born in Spitalfields in London’s East End, the youngest son of Jewish immigrant parents. When he was a year old, the family was forced by extreme poverty back to their native Galicia (Poland). His father travelled to America in search of work, but when this plan failed the family returned to London in 1896. As a boy he showed a marked talent for drawing, and on leaving school in 1906 he enrolled in art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic, which was the first institution in the UK to provide post-school education for working people.

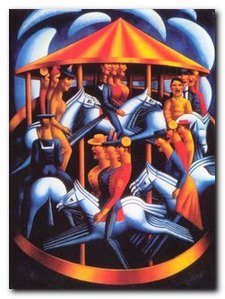

Mark Gertler (1896—1939) was born in Spitalfields in London’s East End, the youngest son of Jewish immigrant parents. When he was a year old, the family was forced by extreme poverty back to their native Galicia (Poland). His father travelled to America in search of work, but when this plan failed the family returned to London in 1896. As a boy he showed a marked talent for drawing, and on leaving school in 1906 he enrolled in art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic, which was the first institution in the UK to provide post-school education for working people. In 1914 he was also taken up by Edward Marsh an art collector who was later to become secretary to Winston Churchill. Even this relationship became difficult, since Gertler was a pacifist, and he disapproved of the system of patronage. He broke off the relationship, and around this time painted what has become his most famous painting – The Merry-Go-Round.

In 1914 he was also taken up by Edward Marsh an art collector who was later to become secretary to Winston Churchill. Even this relationship became difficult, since Gertler was a pacifist, and he disapproved of the system of patronage. He broke off the relationship, and around this time painted what has become his most famous painting – The Merry-Go-Round.

In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and

In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and